Originally released in 1987 for the Apple II and the Commodore 64, Maniac Mansion is a point-and-click adventure game produced by Lucasfilms Games that takes classic horror and sci-fi movie tropes archetypes, and subverts them to create humor and parody the genre. There are many noticeable horror/sci-fi clichés right off the bat: a secret lab, a haunted-house setting, a dungeon, blood and radioactive slime everywhere, aliens, and others. There are also identifiable villain archetypes, such as the mad scientist Fred who wants to steal people’s brains and the sentient monsters Green Tentacle and Pink Tentacle. What makes Maniac Mansion unique, though, is that while it taps into these tropes, it does them sort of ironically—they subvert their horror-inducing power by introducing mundanity to them, and ultimately upends the villainy of the mad scientist and monsters through the absurdity of the final villain, the sentient Purple Meteor.

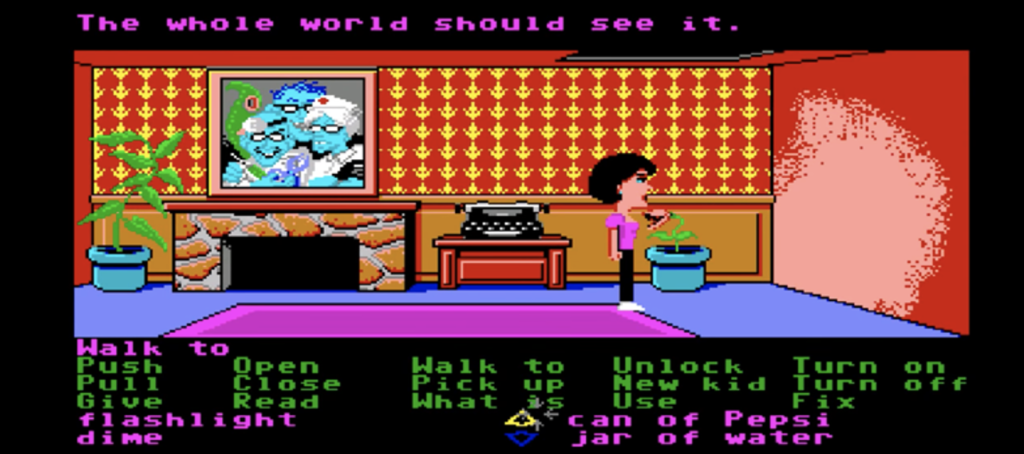

Firstly, the graphics in the game are bright and colorful, right off the bat making it less ominous that its contemporaries in horror films and horror games. Its music is also generally upbeat, rather than slow and foreboding. Also, as mentioned, the game has somewhat of a “haunted house” or “house or horrors” setting, wherein the characters are chased around the house by the mad scientist, his crazy nurse wife, his maniacal son, or his two henchmen (Green Tentacle, Pink Tentacle). The mad scientist and his wife and son are even coored blue, slightly reminiscent of Frankenstein’s monster (likely a homage to that revolutionary mad scientist). However, the fact is that the house does not look scary. Like the rest of the graphics, the walls are colored pink, purple, green—bright and generally unthreatening colors. The bedroom of Fred and Edna is decorated very cutely, and the house looks very domestic, with family photos and well-maintained houseplants. Even the son’s bedroom is decorated like a stereotypical American child’s bedroom.

The mad scientist and his family are humanized through these decorative elements, making them less “villain-like”—he seems more ordinary, more like any other family guy, which creates a humorous dichotomy. He has a secret lab, but also lives in a suburban American home. This subverts an expectation about evil mad scientists in horror films being practically inhuman.

One of the mad scientist’s henchmen, Green Tentacle, a disembodied tentacle jumping around that likes Pepsi, is also humanized, though not through any sort of deep emotional revelation, but by a very mundane one—it wants to be famous. It laments that it wants to make music and join a record label, even inviting two of the characters to join a band with it. This very ordinary struggle, a trope in it of itself, makes it so the Green Tentacle does not seem malicious, and even relatable. This makes it less frightening despite the horror trope it is supposed to fill. It subverts this expectation that monsters/henchmen in horror films have no personal motive, that they are not really capable of complex emotions and desires like humans.

The final villain in the game is the Murderous Purple Meteor, the manipulative mastermind behind the horrors of the house, who brainwashed the mad scientist into a life of villainy. First of all, this reveal is ridiculous in it of itself because it is a talking rock. The rock can’t even move by itself. It has no facial expressions. It is so ordinary. This subversion of expectation, this anticlimactic reveal of a very unimposing final boss is humorous and parodies other “final boss” reveals in other games. Also, the Purple Meteor, just like the Green Tentacle, is not so one-track-minded evil as other horror movie villains. It just wants to be famous—it wants to be a published author and be famous. Even this sentient rock submits to the temptations of capitalism.

There are also aliens in the game, but they are certainly not villainous, even though they’re bright green and fly UFO’s like a stereotypical alien. The aliens are humanized as well—when Ben, one of the characters, calls the wanted persons hotline having found the Murderous Purple Meteor, who answers is just an alien cop, who has just pulled over an alien civilian for speeding in its UFO. Again, the alien, traditionally a villain, is humanized not through some emotional connection with the reader, but through involvement in this mundane occurrence. This is again a subversion of expectation that is humorous and serves to parody the role aliens traditionally have in sci-fi/horror films.

So overall, I think that Maniac Mansion pulls off this parody of horror films very well because it is actually funny. It takes these horror tropes and makes fun of them, but it is not just absurd humor. Instead, it introduces an element of mundanity, humanness, into the tropes, which takes away their horrific power and just makes them, well, ordinary. And that dichotomy is what makes it comedic.

My only wish is that I noticed that the game also plays into some traditional horror tropes regarding women in the genre. That is, the main motivator for the teens to enter the house is to save Sandy, a young blonde college-student. Sandy is the first victim, and once her friends enter the house, the mad scientist goes after the others. This reminds me of slasher films, where the targets are often young people, the first target often being a young woman. However, Sandy plays no other purpose besides being a damsel in distress, the dumb blonde teen who is the “first to die” (although she doesn’t actually die, so more of “first to get caught”). I wish that the game found a way to subvert that trope as well, maybe give her more interesting dialogue to banter humorously with her captor. I feel like this is a horror/teen film trope that was included but was not subverted, like others.

I also played Maniac Mansion for the Retro game review, and I really like how you analyzes the mundanity in the horror elements of the game constructs the absurd and comedic world view in the game. By doing this, the game surpasses the linearity of horror but provokes the player to reflect on what constructed and subverted the horror-inducing power in an ironic way (and even empathize with the absurdity???).