Donkey Kong Country creates a perfect balance: balance of difficulty, complexity, and control, and even the distinction between gameplay and deeper messages. Allow me to explain:

Difficulty

To start, the game is not easy. Enemies fill every level, and it only ever takes one hit to take out Donkey or Diddy Kong. I played this game on Nintendo Switch through the SNES emulator, and I abused its rewind feature constantly–but even if I hadn’t, the game is forgiving where it counts. Unlike the original Super Mario Bros, Donkey Kong Country doesn’t skimp on extra lives. Not only are DKC’s Extra Life Balloons and bananas far more common than Mario’s 1-Up shrooms and coins, but DKC also lets players go back to collect them again. Cranky Kong and Funky Kong even say this in their dialogue, suggesting: “In Jungle Hijinxs, stick to the tree tops to earn extra lives”, and “You dudes need some lives or something? Jungle Hijinxs is the place for that!” respectively.

That forgiveness makes room for accessibility. The intention shows in the instruction manual where it specifies that the two player mode is “a great way for a younger player to play along with an older, more experienced player.” The design of this game had the younger and generally inexperienced audience in mind. They did not, however, forget to please their skilled playerbase. The designer, Gregg Mayles, stated that if a player had the right timing, all the obstacles would line up and allow them to move quickly and cleanly through the level. Moving forwards to today, we see this mindset everywhere even in difficult games with easier settings or even “God Mode” features like Hades’ damage reduction setting.

Complexity & Control

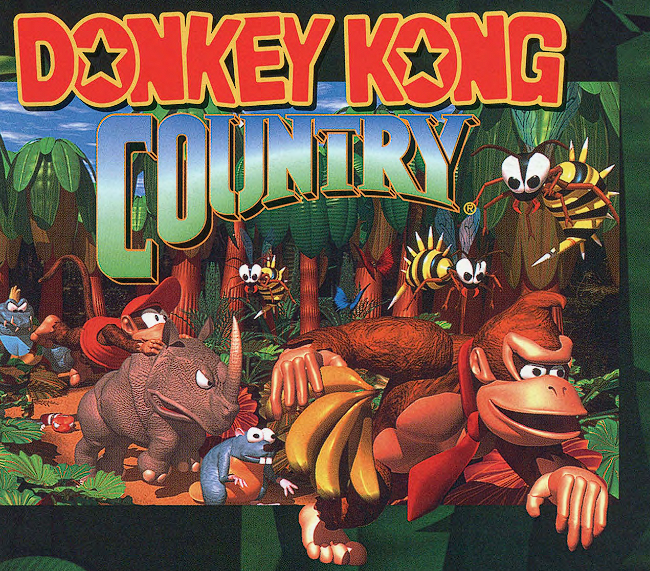

The game also balances complexity to a point where it has variety, but never feels overwhelming. Donkey and Diddy Kong can occasionally find a small cast of animal friends in boxes whom they can ride, but though they liven and change up the experience, they really serve more to simplify the level than complicate it. As examples, Rambi the Rhino just plows through enemies, and Enguarde the swordfish makes water levels much easier to navigate, giving the ability to attack and also the luxury of moving around using just the D-Pad instead of mashing A to swim.

Creative level design also helps make the game always feel fresh, like when instead of a platform, players need to jump on a vulture in mid-air. It feels skillful and fun, but never too mechanically demanding. When it pushes it to a new height, like with three vulture jumps in a row, instead of requiring it to traverse a long chasm, the game uses it to give extra rewards like a KONG letter or some bananas for players good enough to perform it.

Control plays a similar role through the barrel cannons, where some of them fire immediately, and others need player input. It’s a lot of fun to get launched around the level automatically, and the game makes sure it doesn’t become stale by later introducing the manual cannons. This relationship gets more complex when they combine together and move–one level has a manual cannon shoot into an autocannon, which then shoots into a third, moving cannon. The timing required on that is intruigingly difficult to get a hang of because of that separation caused by the middle autocannon.

Gameplay & Message

Perhaps most importantly, what Donkey Kong Country does is create a distinction between the gameplay and the message. Though the former can help support the latter, the message does not take over and worsen the gameplay in a needless attempt to eliminate all ludonarrative dissonance. Once players enter Kremkroc Industries Inc, they’re met not with the beautiful jungle or pretty cave scenery, but rather with an industrial hellscape, with dystopian steel factories and a level literally called “Poison Pond” where the water is green and all the level walls have faded from their wonderful blue to a dead, dark copper. It was only after seeing this that I started understanding some of the subtext of the game.

To regain Donkey or Diddy Kong after they take damage and flee, players have to reach a DK barrel, where they can hear the appropriate Kong banging on the inside and screeching–combining this with the fact that every animal friend comes from inside a wooden box, and that the story of the game literally hinges on this group of industrial reptiles and their goons stealing Donkey Kong’s resources (bananas), an environmentalist point of view becomes exceedingly obvious. It’s a fantastic message, made better for the fact that it’s not completely in-your-face all the time. Donkey and Diddy Kong still beat up Kremlings despite them being crocodiles, vultures, and orangutans. Nothing about the gameplay was forced to change because of that underlying message. It avoided the fate of many games, mostly educational, where the driving force of intent completely overrides the other goal of having fun.

Nice review! As an avid fan of Donkey Kong Country Returns and Tropical Freeze, I appreciated the read. It is interesting to see how the DKC franchise always dealt with some sort of social issue in its storytelling. As you point out, there was a clear theme towards the end of industrialism and dystopia, and I’ve noticed other social themes portrayed in the newer games. Tropical Freeze definitely seems to be a commentary on colonialism and occupation, as the ice villains overrun DK Island and kick the Kong family out. It reminds me a lot of how you bring up the Kremlings in the original. I also like how you pointed out the difficulty of the game. I’ve always felt that the DKC franchise was way less forgiving than 2D Mario platformers, and the way you explain how the game handles difficulty was definitely compelling. Hoping they complete the DKC Returns trilogy!