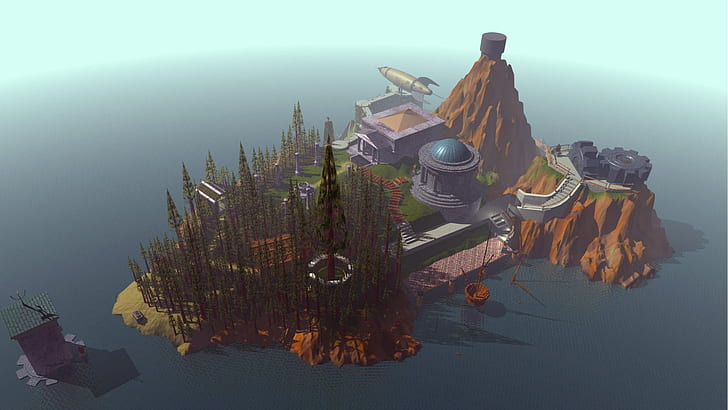

I was captivated by Eric Rosenfield’s “Doom, Myst, and the War for the Soul of Video Games”, and upon finishing this reading, I decided to look at the comment section. Here, a comment from a user named ‘Mark’ caught my attention, and my curiosity led me down a rabbit-hole of arguments, including posts on change.org and Reddit. In summary, user Mark argues that Myst has great nostalgic value, particularly for “those of us who craved accessible content in the ’90s”. However, nostalgia cannot cause us to overlook criticism or censorship, and we must acknowledge that Myst employs sexist tropes and game mechanics that enforce/internalize misogynistic ideology. This causes issues when considering Myst’s ‘resurrection’ as a TV series or movie, as this would also resurrect or recreate its sexist and misogynistic issues (the TV series mentioned has now been scrapped, but this doesn’t affect the argument). It is worth noting that this argument focuses on the sequels of Myst, not the original game, particularly due to its lack of character interaction.

It turns out this argument has two clear sides, and some people are very passionate about it. Although I do not feel like I know the theory or content behind the argument well enough to form a strong opinion, I will attempt to show both sides, and let you decide how you feel.

One side, in accordance with user Mark’s argument, can be seen in a change.org petition named ‘Stop movie based on sexist Myst video game series’. This side argues that although it is nostalgic, and “practically made in a basement (casting the creators and family)”, the Myst series cannot be excused from misogyny. They draw in examples from sequels of Myst, such as Riven: The Sequel, which “is a sexist video game in that it utilizes the damsel-in-distress mechanism”.

The other side can be seen in the comment section of a Reddit post that refers to the change.org petition mentioned above. They argue that even though a game uses a sexist trope, it doesn’t inherently make the game sexist. Further, Myst and sequels have a variety of ‘badass’ female characters, whereas the majority of male characters are “complete madmen with God complexes” (which cannot make it misogynistic? – I didn’t really understand the argument here). Finally, certain commenters argue that the people in the change.org petition are too ‘easily offended’, and that it is “not worth a fight”.

Ultimately, I think this is a good example of how disagreement can occur in understanding videogames and gives us an insight into how certain people voice their opinions about videogames. It also highlights how intolerant or dismissive certain people are, which I don’t believe is positive.

*On a side note, one comment that I do not agree with, is that of user David Markham in Eric Rosenfield’s original blog post, who says, in response to user Mark: “Try to stop reading socio-political meaning into everything. Sometimes it’s just a game and some people like ’em and some people don’t”. I think we can all agree that even if you don’t like user Mark’s argument, analyzing and criticizing videogames is extremely important.

“Doom, Myst, and the War for the Soul of Video Games” (Eric Rosenfield): https://literatemachine.com/2020/11/20/doom-myst-and-the-war-for-the-soul-of-video-games/

Change.org petition: https://www.change.org/p/stop-movie-based-on-sexist-myst-video-game-series

Reddit post: https://www.reddit.com/r/myst/comments/clpczt/i_dont_want_to_be_in_this_world_anymore/

Filip, I really like this blog post. The dual perspectives you summarize are highly informative and revealing, especially in context of the success Myst had with women. I wonder if this still the case as was in 93?

When reading the two arguments you illustrate two common views: those being that a game hold certain ideals irrespective of intent and context or that the game does not, and that intent does matter and changes the impact of the tropes in a game. At risk of generalizing, it sounds like the contention between your arguments is the role of intent in production, especially in the realm of possibly provoking or angering a demographic, and if intent should matter at all.

I’m also very curious about the initial reception of Myst among the (largely female) fan base back in ’93, and whether there was much discussion of misogyny or the damsel-in-distress trope back then. It would be interesting to see the demographic breakdown between the two arguments you present as well – were there many women who agreed with the Reddit post, that people are being too sensitive? Or were women more frequently backers of the change.org petition?

It would be interesting to see a proposal written for a Myst movie by some of the original female fans. Would they change the game’s plot at all to alter the misogynistic elements? Or would they choose to stay true to the original material? And what would be the wider fan reception of a videogame movie produced entirely by women, based on a game with misogynistic elements and a large female fanbase?

This is a really intriguing point, especially considering that more Myst players were female and not male. This also leads me to think about how even for games made for women, they still employ sexist ideals: in the early 2000s, most of the girl games were either about cooking, babysitting, or dress-up. They were about things that society expected women to like, while the male realm was much more diverse. Still, in the early ages of videogames, the demographic of male gamer was not very diverse. It just seems to take time to evolve past these habits. Though, would it be a good thing to get rid of these sexist tropes in a remake of Myst? To ignore the past mistakes? I am not so sure.

This is fascinating idea to look at, especially as games become more immersive with new technology and can now implore a multitude of digital facets to tackle challenging social concepts. I wonder how future game design, especially in a VR world, will have to think critically about respecting social values while still trying to maintain a, arguably old-fashioned, sense of tradition.