“Myst might have been the last time (maybe the only time) a top-selling game of this class had more female players than male ones,” Rosenfield writes in his analysis of “the soul of video games.” Chief among the reasons for Myst’s success was its anomalous popularity with women and girls, a group who had been ignored in video game creation and marketing– or so Rosenfield claims. Finally, there was a game on the market without the testosterone-infused narrative of killing and maiming– now we had a game where you fell into a fantasy world rather than a space station, a game where being beautiful was more important than being cool. Finally, there was a game that girls would like.

For some reference, Myst sold almost twice as many copies as Doom, though only one of the two games would go on to shape video games as we know them now– and surprise! It’s the one that sold less.

Rosenfield writes that “[t]here was a moment in the 90s where this seemed like it wasn’t going to come to pass, where the popularity of Myst and the drive towards narrative games aimed at a wide audience might have created a gaming culture more like the general culture.” This moment was thwarted by the popularity of the FPS genre, and in turn, adventure games like Myst– games that appealed to women just as much as men– were dwarfed by the massive, masculine reception that Doom enjoyed.

In his article, it’s easy to think that from here until perhaps the first Sims game, the world of video games comprised solely of disappointing Myst knockoffs and one-off Doom remakes that would go on to shape the future of first-person shooters. He frames this solely as a capitalistic consequence– that the industry evolved the way it did because of Doom‘s success. But one game complicates this, a game that outsold Doom just as Myst did even without a gender-neutral marketing scheme– 1996’s Barbie Fashion Designer.

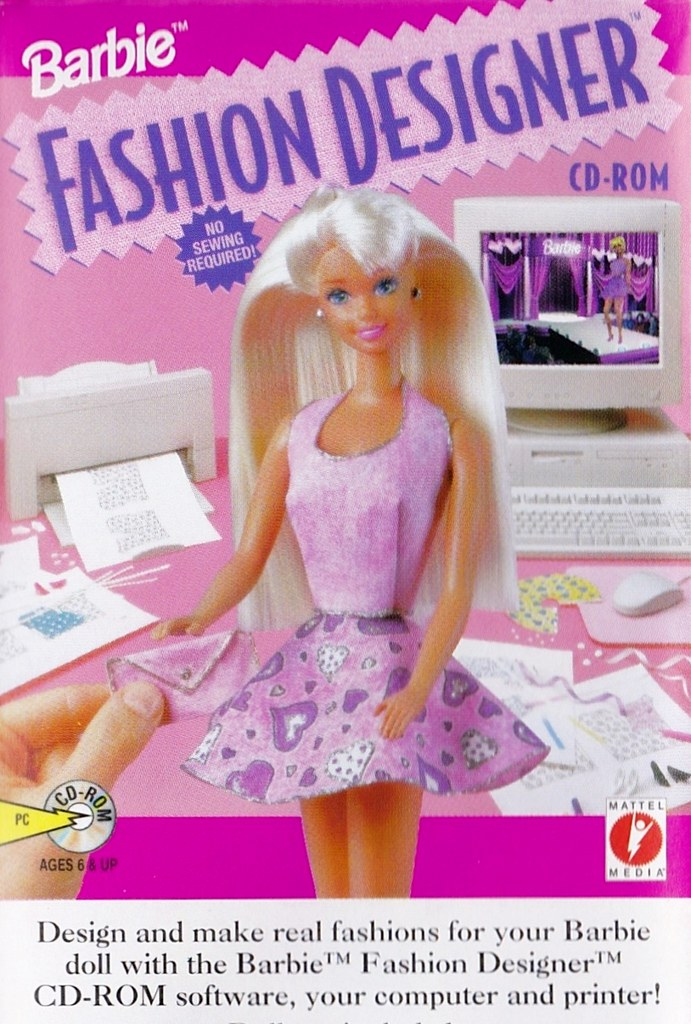

The game is exactly what it sounds like: players are allowed to design clothing and style outfits for Barbie and various Barbie-adjacent characters, with the added feature that they can then print their designs and translate them into real-world clothing for their real-world dolls. Published in 1996, it closed out the year as the sixth most popular game– outselling both Doom and its myriad clones.

So where does this game that, in a world of incredibly gendered toy marketing, ignores the male population– games’ alleged target population– fit in? How can it give us insight into the gaming practices of 1990s females, and how does this impact Rosenfield’s argument?

For one thing, Fashion Designer’s success refutes the quote that began this article. Myst is not the only game of its scale to sell to more females than males– Barbie and her pink dresses and high heels would arrive three years later to blow that out of the water. And though both outsold Doom, neither genre– games that either appealed in some part or wholistically to a female population– would go on to see the impact that Doom had on games going forward.

This is not just capitalism at play, as Rosenfield argues. This is in relation to the argument with which he begins his article– that gaming is a male-dominated, male-marketed, and male-received field, with the idea of female “gamers” brushed under the rug when it comes to production choices. Barbie Fashion Designer and Myst combined proved in an era of misogyny that there existed a vast and paying population of women ready to join the gaming world. When it comes to answering the question of why they didn’t see the future success and replication that Doom did, the stigma and idea that women cannot enjoy video games was almost assuredly some part to blame. If money was all that was on the mind of producers, advertisers, and developers, they were passing up a golden opportunity to make a quick buck off the girls perfectly content playing with their dolls in a whole new way.

I really appreciate you bringing a game like this into the conversation! My only wondering is whether Rosenfield would qualify his statement’s use of “this class” of video game to refute your argument, insofar as I took a big part of his argument to be that Myst is a relevant game to consider with gendered promotions of games because of its fairly (gender) neutral mechanics. Barbie Fashion Designer leans so heavily into the girl-aisle tropes of our time, which I wouldn’t say is exactly what Rosenfield’s argument was getting at in regard to Myst vs Doom, but I’d love to hear other’s thoughts on this!

I think it is incredibly ironic that Rosenfield employs arguments about sexism and then conveniently leaves out a female-marketed, hugely successful video game. I wonder if he saw this as a video game at all? While I think he was arguing about gender-neutrality (Myst) vs masculinity (Doom), I think he misses out on a large part of the spectrum by not including femininity. By doing so, he created a false duality of Myst vs Doom. Another interesting fact to point out is that some people consider Myst and its series to be misogynistic, which means that it was not even wholly gender neutral. Rosenfield’s arguments leave a lot to be considered.

I love the irony of how a video game like Doom was outsold by a Barbie game. The fact that even games like this are left out of the conversation about games proves your point of women being left out of gaming since it’s seen as a masculine subject, especially in the 90s. It’s crazy to think that the effects of this marketing are still highly apparent today.

Very interesting point, and it certainly is ironic that this game ended up outselling Doom but it makes me wonder what other games Rosenfield could have potentially overlooked by stating that Myst was the last time a top selling game had more female over male players? I don’t have the statistics but DS games from the early 2000’s like Nintendogs comes to mind when I think of games that potentially had larger female playerbases. The Nintendo DS marketing was fairly gender-neutral from what I’ve seen and it was mainly marketed as a cool new handheld gaming console for all kids and I think Nintendo as a company is overall a really interesting thing to consider marketing-wise because consoles like the Wii and Nintendo DS I feel like performed so well because they were marketed towards a wider audience and to families as opposed to XBox or PlayStation which felt more like they were going for the “hardcore gamer”. I wonder if there could even be more recent examples as I feel like many cozy/farming sim games have very large female playerbases but maybe the question of whether it is larger then the male player base is up in the air.