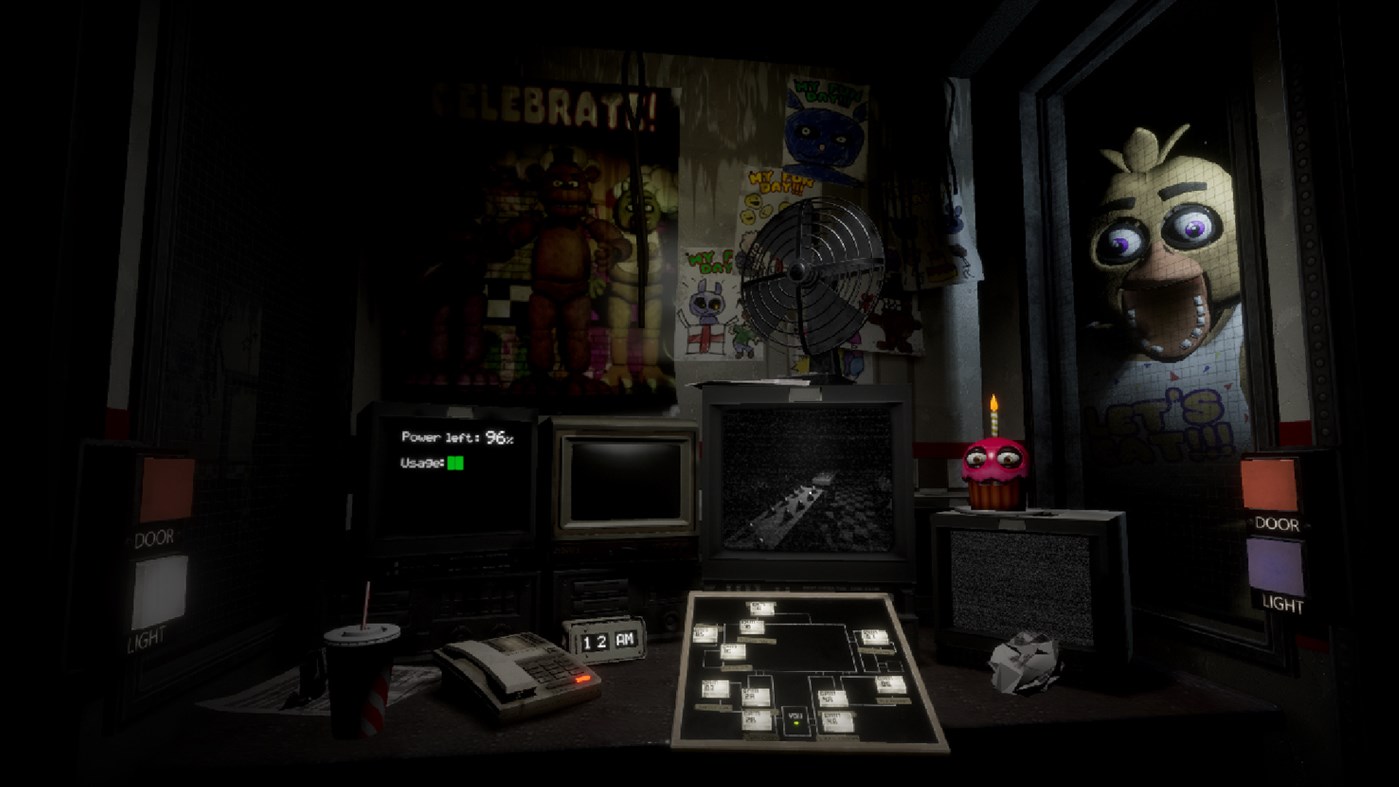

It feels like common knowledge that most things that stake their identity on being edgy or transgressive can quickly become old hat, cliche, bo-ring. The idea that Elvis’s pelvis gyrations could’ve caused a storm of controversy in the 50’s is basically laughable now, and the grunge culture of the 90s can often seem dated and shallow now—stuff for dads, and Limp Bizkit. But at the same time, it seems like over the past 10 years or so, the most shocking games have often, continually become the most successful—at least, numbers wise, virality-wise. Happy Wheels went viral in the early 2010s off the back of its extreme gore, along with countless horror games (Five Nights at Freddy’s, Slender, etc), games marketed as “difficult” or “gory” (Super Meat Boy, Binding of Isaac, etc), and so on and so on. So why is it that these games keep succeeding, despite often having superficially similar premises? And what made a game like Doki Doki Literature Club stand out from the crowd?

DDLC, for all intents and purposes, pretty much capitalizes on the same of the internet’s instincts that, say, Five Nights at Freddy’s did. It’s shocking, it takes well to facecams and other YouTube videos, and it thrives on people telling their friends to go play it “blind”—it’s practically begging to spread by word of mouth! In that sense, I guess DDLC isn’t different. But how come DDLC has become acclaimed and studied when even successful games, such as FNAF, have fallen by the cultural wayside? That is, to say nothing of the countless games that fall in similar categories and fail to garner any traction at all.

I think the fact that we’re studying DDLC in the first place has something to do with it—it’s a game with a lot of layers, and a lot of very clear commentary on the genre it ostensibly forms a part of, as well as internet “anime culture” in general. In this sense, it’s a bit like Neon Genesis Evangelion, providing meta-commentary on something extremely near and dear to much of its primary audience’s hearts: otaku culture, the sometimes perverse nature of projecting onto fictional media, and depression.

These obviously aren’t complete thoughts, and what makes a game successful and lasting or what makes fiction have an affect on a person are questions that, if I could answer them definitely, I might not be taking this class! But DDLC, while rising above the crowd to a certain extent by virtue of its shock and horror, seems to stay with its players via what it actually has to say, and what its creator was thinking about when making it.

Just a quick thought from me, I really like what you’re saying here. DDLC was (at least according to the author) explicitly designed to draw in people who had never played visual novels and it shows. It’s not hard to trace some of the ways DDLC was designed to go viral (shock value of the suicide jumpscare, or the file-type-polymorphism of the .chr files that sparked so much conspiracy), but it leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Sure, DDLC was designed for a specific audience and it hit that audience en masse, and in doing so it made some messages that have allowed the game to stay relevant. But now I really don’t like how the game’s distasteful, heavy-handed treatment of serious mental health issues was basically a tool to get YouTube clicks. Sometimes, (like many of the shock examples you gave,) shock-value is good. But I think DDLC is an example where intentional use of shock to generate discourse isn’t always a great plan.