The Oregon Trail is an educational game first released in 1971. Created by three student teachers from Carleton College, this game was originally designed for a middle school’s history class. The avatar is a 19th century pioneer of the famous Oregon Trail and leads a group of chosen settlers. To successfully finish this 2,000-mile journey that spans from Missouri to Oregon, players need to use resources efficiently (eg. purchase food and ammunition, change food ration and travelling speed, hunt for food, etc.) and deal with unexpected situations along the way (eg. disease, theft, bad weather, broken items, etc.). Both the first and later versions of the game wan huge popularity among North American schools, accumulatively affecting millions of students and making itself one of the most successful educational games in the history. After playing this game myself, I came to see the beauty of this game and the great potential of educational games to revolutionize people’s learning processes.

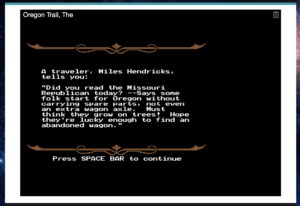

The success of The Oregon Trail lies in its shift of the relationship between players and the knowledge. Unlike traditional educational practice which teaches students what is important and forces them to remember key concepts, The Oregon Trail makes players actively engage in the knowledge-memorizing process. Here, every landmark that the avatar arrives at and every person the avatar interacts with might contain important information that critically determines the success in later rounds, while all the key information is blended with other less relevant yet equally important historical facts that the students are expected to know. Thus, without a clear idea of what is crucial to the success of the game and what is not, players need to carefully read through and even memorize every piece of information brought up in the game. For example, before the avatar sets out, one key piece of information that the player gets by talking to the local is the importance of purchasing six oxen in order to win. Players can still go back and adjust their purchase based on this if the number of oxen they buy differs from six. In this way, players not only get hint about the game but also learn about items travelers carried along on the trail in the past.

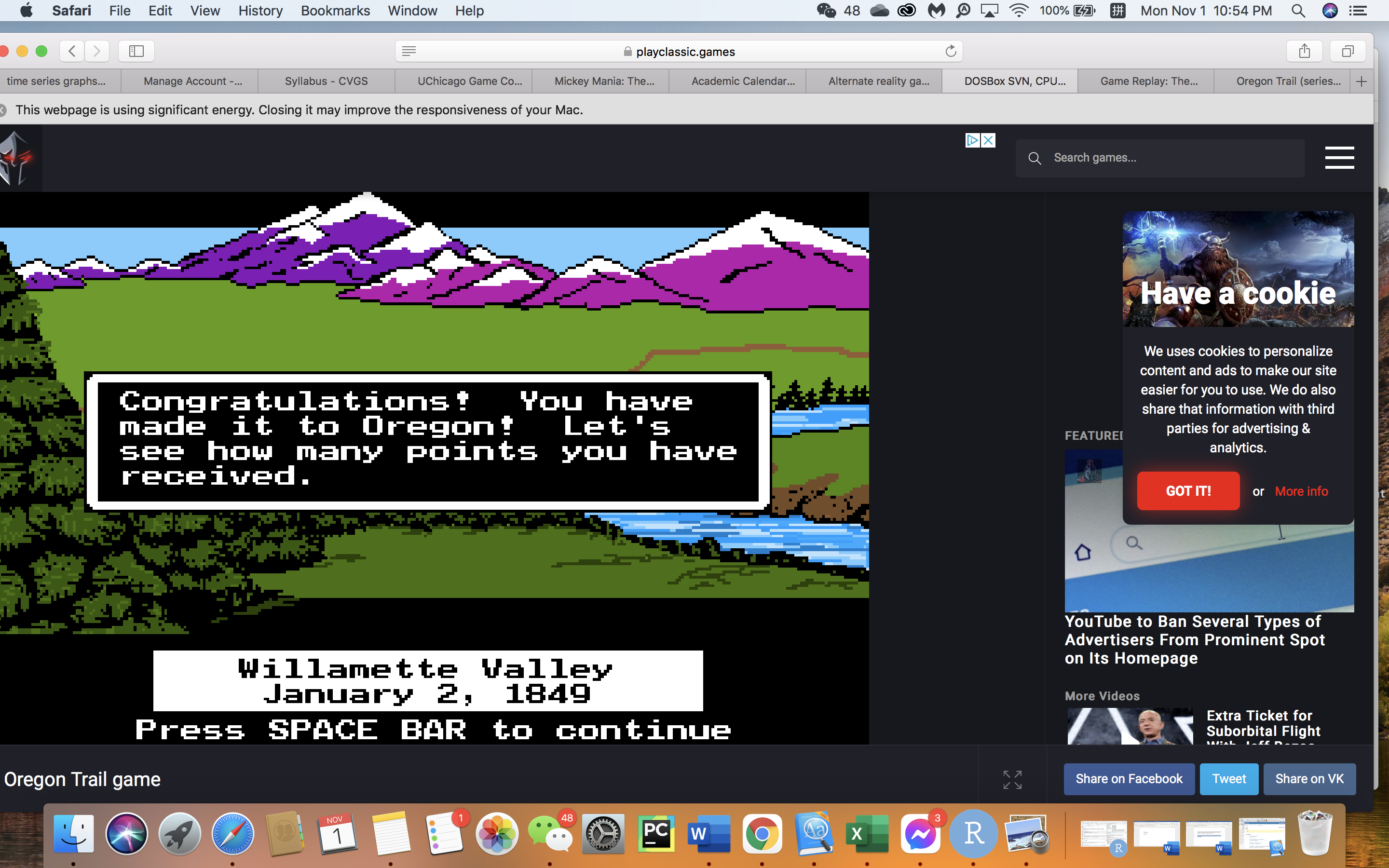

Additionally, rather than throwing all the information—relevant to the game or not— at the players, The Oregon Trail intentionally hides all the key information and triggers players to actively seek for it: it is up to the readers to decide on whether to talk to the locals, and players only get one piece of information after successfully arriving at a new landmark. Knowledge here becomes a reward, something that one makes effort to get and needs to cherish. Essentially, The Oregon Trail abandons the traditional passive relationship between students and course materials and offers a new learning mode that encourages active knowledge acquisition.

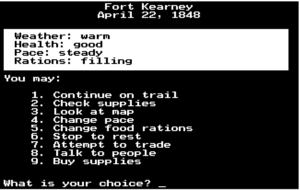

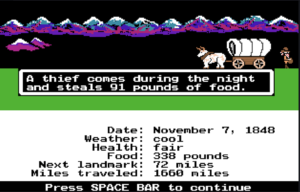

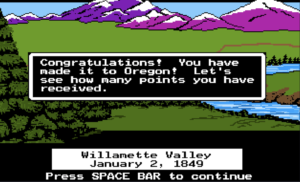

Besides making changes to the means students encounter knowledge, this game also changes the way students process knowledge by creating situations that allow them to put what they learn into practice. As what Ian Bogost argues in his book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogame, video games use process persuasively. Just like many other educational games, The Oregon Trails uses processes rather than language to make explanations. For example, to let students better understand the geography of the trail, at certain points the game will ask the players to make decisions on which direction to go into. In order to make the right choice, players need to carefully study the map, or their wrong choice will lead to serious consequences. I learned this in a hard way. When I was playing the game, I once ignored the map and chose the wrong path, which directly led to the exhaustion of the food and caused the death of the avatar, forcing me to start the game over. It is worth mentioning that the frequency and details of the random events along the way, such as weather change and diseases, are carefully set up based on historical records to more accurately reflect the real situation. Hence, by playing the game and engaging in this process, players will have a more well-rounded understanding of this historical period and better make sense of the knowledge that they acquire. In other words, by placing players in this virtual setting and having them go through this game process, The Oregon Trail demonstrates clearly where the knowledge comes from and how it should be utilized.

In a nutshell, The Oregon Trail is a great example of the educational game genre and explores how video games can offer new education methods. Its innovation in both knowledge acquiring and digesting processes abandons traditional passive teaching mode (where students are forced to remember whatever is given to them) and shifts to a more active and engaging learning process. With smart design in the game mechanics, students here take the initiative to seek knowledge and apply them in this virtual environment to gain a better understanding and deeper memory. What will the future of education be like? The Oregon Trail definitely offers many possibilities and gives us hope.

References

- Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007.

- The Oregon Trail (updated version). [Don Rawitsch et al.]. MECC. 1990. Video game.