“Interactivity is an essential part of every game’s structure and a more appropriate way of examining and defining video game genres.” (Wolf, 2) In Wolf’s article, he places a central emphasis on player’s experience to categorize video games and believes that player’s interactive experience is the basis for classifying video games (Wolf, 3). This sense of interactivity gives players a direct feeling of responsibility and allows them to perceive the environment/ setting more vividly.

As a person new to video games, I started to feel the unique power of game’s interactivity that draws the players to a world it creates and leaves a message that hits them profoundly. In Hair Nah!, the central mechanic of the game is to let players control the avatar’s hands to slap away others’ hands that try to touch her hair. The growing frequency of unpermitted hands reaching out to touch the hair, together with the noisy sound, made the game harder and caused a lot of chaos while I was playing it. In the last round, I constantly missed hands and got irritated. The agitation of failing to get rid of all the hands allowed me to vividly feel the frustration black women face in their everyday life, and this central message from the game hit me more effectively than any other perceivable media genres, through its interactivity.

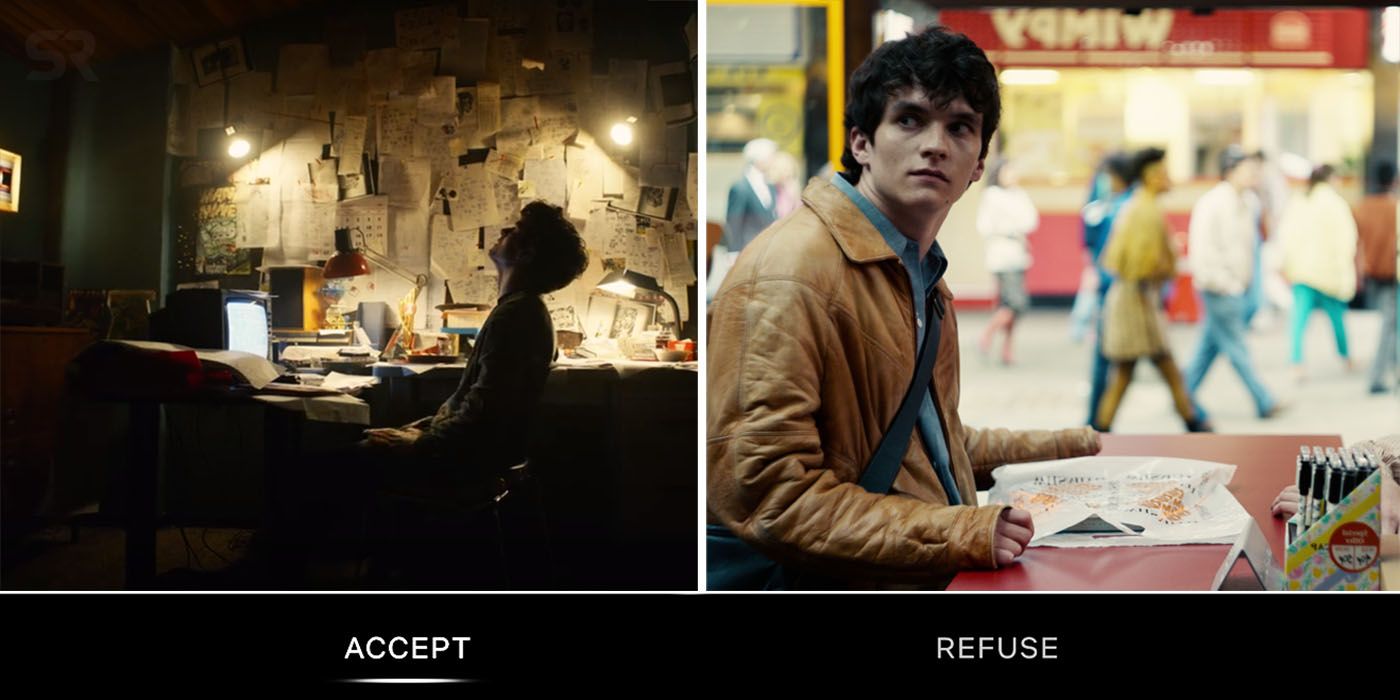

However, narrative and iconography are not irrelevant to video games. According to Jagoda, games take inspiration from the storylines of literature and films, especially genres that “are most invested in world-making and spatial storytelling. (Jagoda, 140)” After reading these two articles from last Tuesday that both highlight videogame’s interactivity as something unique compared with literature and films, I was reminded of Netflix’s film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) that aims to bring the element of interactivity to films and extend the boundary of this media form. In Bandersnatch, viewers are invited to participate in the progress of the story and make decisions on the plot. More specifically, when characters are in major decision-making moments, the film will pause, offer a few options on the screen for viewers to choose from, and have the plot go on according to the decisions they make. The significance of viewers’ choice varies in the film—from choosing what cereal for breakfast (little impact on the progression of the story) to making decisions on whether to let the protagonist or someone else jump out of the balcony and commit a suicide (huge impact on the plot).

These interactive moments in the film appear to give viewers agency in deciding on what to see next and bring the aspect of interactivity to the film, yet their decisions are still being monitored and guided by the film to head in certain directions. For example, if viewers choose to let protagonist commit a suicide, the film will pause and ask them to go back and choose again. It is like walking in a labyrinth with a couple of exits: we appear to decide for ourselves on where to go, but at the end of the day we are still restricted to walk in this certain area and our appeared success of escaping from the labyrinth is merely because our routes comply with what the architects expect. There is only this illusion of freedom in Bandersnatch, and the interactivity of the film does not place viewers’ experience at the center but serves the purpose of the film’s narrative.

What about Hair Nah!? What is the difference between Bandersnatch and Hair Nah! in terms of interactivity? What can their difference tell us about interactivity in relation to narrative? In one aspect, both works have a few settled endings: in Hair Nah!, players either fail or succeed; Bandersnatch only offers a few possible film endings. Our interaction with either the game or the film will leave an impact on the outcome of the works, yet this interactivity in either films or video games does not lead to total freedom but a restricted space with a set of possible outcomes. Nevertheless, the interactivity in Bandersnatch only takes place to push forward the plot, while our participation in Hair Nah! and many other video games actively contribute to the progress of both the plot and the outcome— that we win or lose totally depends on our performance in the game. In this way, the interactivity in videogames and films differs in the extent of our participation to one of a number of predetermined possible outcomes of the work.

Through comparing Bandersnatch and Hair Nah!, I looked into the possibility of interactivity in films and further explored the concept of interactivity in relation to the narrative of both media genres. Just like what professor Jagoda mentioned during the first day’s class, more and more films start to take inspiration from videogames. I believe Bandersnatch marked a marvelous start of this new set of exploration and look forward to more audacious projects that challenge and extend the boundary of media.

Bibliography:

Jagoda, Patrick. “Digital Games and Science Fiction.”

Wolf, Mark. “Genre and the Video Game.”

Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. (2018).

Hair Nah! (Momo Pixel, 5 minutes)

I think Jessica’s comparison of interactivity in video games versus films is very interesting, especially the point that film may provide have more limited uses of such devices. Reflecting on my experiences watching/”playing” such films, in addition to the limited affect the player’s action may have on the story, the integration of such forks always seems fairly unnatural to me, and pulls me out of the story. While a film tries to get the viewer lost in the narrative, forcing them to pause and make a choice reinforces the fabrication, breaking the suspension of disbelief. It seems to be nearly a reversal of video games that have extended cut scenes that pull players out of the game play. But just how many games have found ways to successfully integrate story in a way that doesn’t diminish interactivity, could there be a way for film to integrate interactivity without diminishing story? For example, narrative television has always had episode breaks built into the medium, and viewers are used to these breaks. Could they be used to implement interactivity, such as if there were two possible sequel episodes to watch?

I was also instantly drawn to the bandersnatch comparison when we were talking about interactivity in film in class, and I agree with you that I definitely noticed an illusion of freedom – it didn’t truly feel like my choices mattered as much as they do even in a game with simple mechanics, like Hair Nah. However, at the same time, I also cannot ignore that my brain is primed to view games differently from how I view films and television. I go into them expecting different amounts of interactivity, I approach my games mostly expecting the gameplay and mechanics to affect both my story and the actual playing of the game. When I approach a film I expect to see a story being told, one that my own actions do not have an impact on; rather, I expect the story of a film to be different to me as opposed to other people because of my previous experiences, and while I expect that from games, I also expect the gameplay and mechanics to factor in. However, as Jessica said, I look forward to more interactive viewing experiences, the “gameification” of cinema as it were