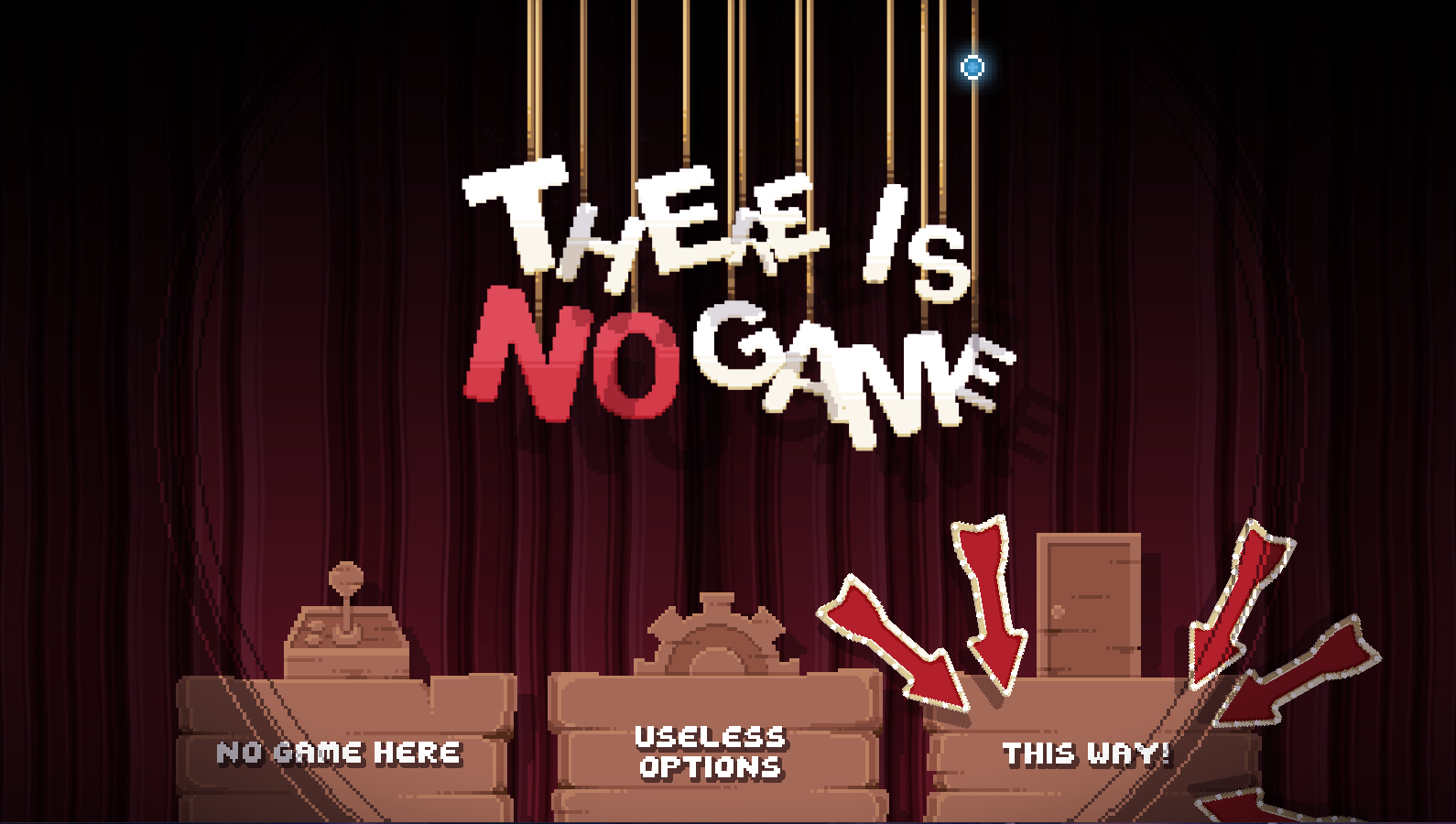

In class, we discussed the topic of video games training us in obedience. We have to think in the mind of the designer in order to progress and often we follow a pre-prescribed path through the game. Some games complicate this idea, like Braid, where at every turn, the player is told to turn back, to stop chasing the princess. We continue on anyways, and it raises two questions. The game we played this week, There is No Game: Wrong Dimension takes this same idea as Braid and turns it into the main gimmick. In every way possible, this game explicitly tells you to exit and stop playing, from the in-game narration to the UI design. If we listen, however, I think it raises two questions.

- If we don’t continue, would it still be a game?

- If we do continue, how does this relate to the idea of obedience?

The first question is more half-formed but something I’ve been thinking about since Braid. If we are to listen to the signs and we do put away the game, what does this mean for the game? Can it still be considered a game if we listen to what it tells us, and we stop playing? Once you reach the end of a game like Braid, those signs are important for delivering its themes and message, but it’s not like the game’s designer truly expects you to listen to the signs and stop playing.

This idea could loop back to the question of obedience. If obedience is the idea that we play the way the designer intended us, There is No Game is an interesting question. We obey what the designer intended us by playing through the game and its various puzzles despite the game being visually oriented and designed around the idea of getting players to exit: from the comically large exit button, to the neon sign board saying “Click Here,” to the narrator constantly begging the player to quit. In order to obey the designer, we have to disobey the game, so in a meta-kind of way, it’s still playing on the idea that we are being obedient to the designer. But that is the whole point of the metagame of There is No Game.

These kinds of messages are interesting and can make for wild and wacky gameplay design or some very deep commentaries on the pursuit of progress. However, the signs themselves are not intended to be taken seriously, as the designer still wants you to continue playing, and this can lightly complicate the idea of video games training us to be obedient.

You bring up an interesting observation. I mean if you think about it, There is No Game is simply telling the audience to “stop doing something” with the intent that they do the exact opposite. If the game didn’t use this rhetoric and instead just told you to “do this, do that”, the player would probably get bored very quickly and the game wouldn’t be half as interesting. The reverse psychology definitely helps with obedience, even though the audience is always subconsciously aware of the designer’s intentions.

I never thought about it like that! I guess for players it’s obvious that a game called “There is no Game” would be a meta-game and would try to do certain things until the game was ‘unlocked’. It’s a lot different from a game like SimNimby which looks like a game, but you can’t do anything in it.

I was also very intrigued by the warning (non-conspicuous at all) flags and other danger-alerting signs in Braid. It was in fact a terrifying experience to look at the flags in the game after knowing all the desperate warnings they were sending, in front of lovely castles and the faithful dinosaur, but I also think its charm largely originates from the fact that this meta concept is not all what Braid as a game was trying to play about. I was in fact less interested in this meta-message when playing There is No Game: its brattiness didn’t attract me at all. And I think this discussion indeed raises questions about the agency with game, i.e. if one person doesn’t continue with something, something/someone else will appear in real life – reality always opens another door. But that is a level of engagement one can hardly replicate in a game.