If you agree that the title is a mouthful of jargon, read this post to find out why it could make sense.

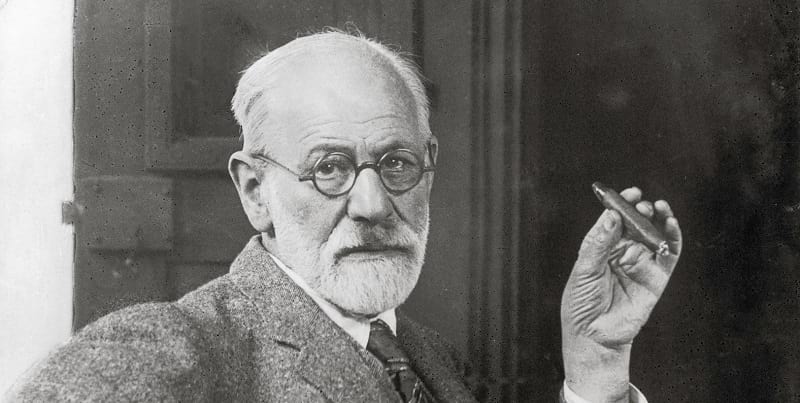

In this post, I wish to further investigate the Freudian idea of the uncanny and how it relates to spatial storytelling/narrative. I will first explain what the uncanny means in Freudian terms, then explain how the Freudian analysis of the uncanny is in fact an allegory for self-consciousness, and explain why self-consciousness enables spatial storytelling. I will present the argument that the uncanny does not follow spatial storytelling, nor the other way around. Instead, self-consciousness lies as a medium between and for the two.

According to Freud, the word “uncanny” contains a dialectic in itself. That is, it means, on one hand, “that which is familiar and congenial,” and, on the other hand, “that which is concealed and kept out of sight,” or the unfamiliar (Freud, 4). Based on this, Freud posits the uncanny as the aesthetic and emotional process of the revelation of something unknown to both others and the self. This unknown is also at the same time very familiar. Because of this, the uncanny is essentially the mark of the return of the oppressed–a thing that’s supposedly familiar but became the opposite due to its oppression/estrangement (Freud himself uses the two terms interchangeably in the essay).

Freud posits that the doubling of self is an essential way through which the uncanny is evoked. That is, the doubling of self is often a spectacle used in narratives designed to evoke uncanny feelings. From this, Freud explains that this doubling of self is a “narcissistic” act of human consciousness (Freud, 9-10). Yet, this double of the self, which initially was so familiar to us, then developed such that it became “a vision of terror” (Freud, 10). For why this is the case, Freud believes that it is because the doubling of self has to be something done out of narcissism by a child in the earliest developmental stages, and that because of this the double is something dating way back in one’s consciousness that it has become unfamiliar (Freud, 10). As such, when this double self reappears, uncanny feelings are evoked.

However, I think that self-consciousness–as awareness, perception, and regulation of self–is more prominently at work in this process. What I mean is: the doubling of oneself is essentially the positing of oneself onto external things, in the primary process of cognizing everything around oneself. That is, how we learn and make sense of the world is through thinking about the relationship the thing has with us, or how the thing orientates around our existence. This drive to cognize things and oneself, which is essential to the positing of oneself onto external things in this interpretation, is “narcissism” for Freud (also a very Nietzschean way of thinking). The difference is, in this interpretation, we are always cognizing and thus always positing ourselves onto any surrounding that we encounter and learn, rather than seizing to posit ourselves onto external things once we grow out of childhood.

So, self-consciousness is the thing that evokes the uncanny. The familiar is myself, while the unfamiliar–the estranged–is that which I posited onto external things in order to cognize them, as well as to cognize me. But the two–the familiar and the unfamiliar–are the same thing, which is myself. And as far as it is myself, it is my self-consciousness.

Self-consciousness is a fundamental building block for spatial storytelling. This is because, in so far as positing myself onto external things is a means of cognizing in which I situate the thing and I in a relationship, I also cognize the thing as it is related to me. That is, the very action of cognizing an external thing entails that I cognize it with myself, i.e., my self-consciousness, in it. Therefore, every time we pick up an item in Gone Home, we are cognizing the item as “I” and with “my self-consciousness” in it. The “I” and “my self-consciousness” here includes two levels, one for the subjective self that the game’s first-person view and controls endow the player with, and the other for the player’s self, which comes to cognize the space of the game through identifying things in the game space with things in real life. At both levels, self-consciousness doubles itself and posits itself onto the things presented by the game space. The two self-consciousnesses are essentially one belonging to the player, which cognizes the game space through a doubled doubling of self, which all return to the real world player such that both meaning and narrative can be constructed by the player, while feelings of the uncanny are produced and enhanced. Necessarily, spatial storytelling requires a player that recognizes and cognizes the space as meaningful. And in so far as it is meaningful space, it is also space that’s able to enter into relationship with self-consciousness. And in so far as it is space related to self-consciousness, spatial storytelling is enabled only when there is self-consciousness.

Works Cited:

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny”. 1919. https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf

Very interesting read! I think the way you implement concepts of Freudian philosophy into the context of Gone Home makes for some very compelling discourse. Considering these more formal, philosophical elements in the space of video games helps us to both better understand this art form as well as to better understand ourselves, our own self-consciousness, and our streams of reactionary thoughts. I think a crucial point you make that speaks to cognizing media as a whole is when you state that “spatial storytelling requires a player that recognizes and cognizes the space as meaningful.” It seems that by this logic, absorbing any sort of media requires you to assign “meaning” to it, and that meaning needs to be able to interact your own self-consciousness. These Freudian concepts appear to speak to media and gaming as a whole, even beyond spatial storytelling.

Very insightful post! I really like how you argue the familiar self juxtaposes with the unfamiliar external collaborates in constructing self-consciousness of the player, which provokes uncanny feelings. The process of exploring the game space provides a process of first experiencing the space construct and then learn about or familiarize with objects that embed memories that constructed the self. The exploration of game space, therefore, is a way of establishing self-consciousness in this simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar experience.