Minor spoilers for Persona 2: Innocent Sin

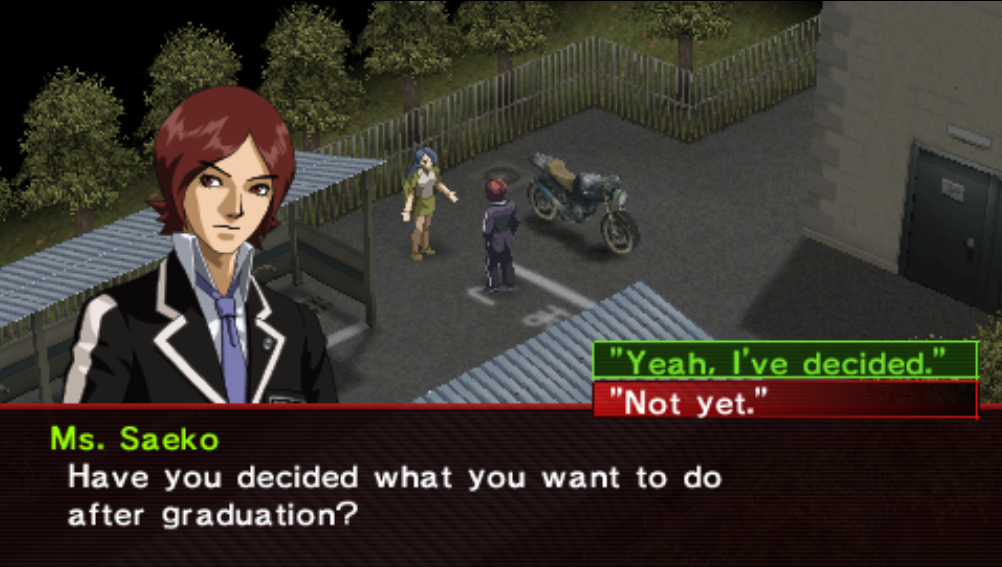

Two years ago, I played through the bulk of the Persona series. When I began the second game (the one which would ultimately be my favorite), I was introduced to the protagonist, who was immediately interrupted by his college counselor. She asked if he had decided what he wanted to do after graduation.

“Oh no,” I, a high school senior, said.

Persona 2: Innocent Sin is an RPG, or a role-playing game, specifically a subgenre called Japanese role-playing games, or JRPGs. Many of the traits indicative of an RPG have spread into the wider gaming landscape, such as character level-ups increasing skills, or choices in armor or weaponry. In a sense, every game is a role-playing game- we always take on an avatar, whether it is Mario or Bigby (shoutout Bruno), but in RPGs this element of player interface is not a bug, but rather a feature. Thus, we can ask of this inexorable element; what does it mean to be in the world of a JRPG? What do these games say us, and the “roles” we play?

The subsection of RPGs that I find most interesting are Japanese console RPGs. They are unique in structure from Western RPGs, which, broadly speaking, grant the player some of the most freedom possible with the player’s avatar-allowing the player to freely create an in-game avatar, from their skills to their appearance, as well as sometimes picking their own backstory, dialogue options, as well as how the narrative is carried out, with games such as the Fallout series and Vampire the Masquerade: Bloodlines, which permit the player to choose between allying with certain factions, which can lead to completely different endings to the game. These also translate to a wealth of mechanical freedom, in choosing weapons and fighting styles, or manners of interacting with the world, such as speechcraft, thievery, or types of magic. In the Elder Scrolls: Oblivion, you can even do whatever this is:

While JRPGs profess some freedom as well (the player is typically allowed to rename characters, and in some rare cases choose appearances), that freedom is considerably more limited. No matter what the player renames the protagonist of a Fire Emblem or Persona game, that character will still retain the same personality and backstory- the player cannot fundamentally alter who they are as they generally can in Western RPGs. In a similar vein, the stories of JRPGs are pre-determined, and the player generally cannot change the events of the story in meaningful ways. The mechanical freedom of JRPGs is similarly limited- characters often are archetyped into certain mechanical roles, and the levels are linear. This is not to say that JRPGs possess no elements of choice (some of my favorites like Final Fantasy 9 and Xenoblade Chronicles boast rich open worlds), but rather that JRPGs commonly relegate the player to what the defined protagonist would choose, rather than allowing the player to make their own choices about the actions their avatar takes in the narrative. The avatar then is not a simple extension of self, or a tool for interaction with the game, but something more.

A “role” is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the character played by an actor.” This, I believe, is the heart of the role-playing in JRPGs. In JRPGs, the player is not afforded a one-to-one avatar for their own choices- the player has been contracted to play the main character, as in theater.

In this way, JRPGs are a tool of storytelling first and foremost. When the player character is inextricably not the player, this individual has the opportunity to take on traits and values and to obtain independent agency in the narrative. In part, JRPGs are then the opportunity to see the world through someone else’s eyes, a new lens to interact with a fictional space. The “role” in this case is literal- the player takes on the role of someone else within their own story.

This point of empathy can be experienced in any form of fiction, yet I believe video games are different as a medium in the capability for conveying roles. In video games, one must personally participate in the story, and actively engage to continue. If the protagonist is to walk forwards, the player must incite them to do so. We personally experience the protagonist’s relationships, battles, and take an emotional journey with them- we do this by taking control of their body and becoming them for the duration of the game. In this way, JRPGs are a form of method acting- learning about different people and experiences in a firsthand way, through literally acting their “roles.” The JRPG can be another way of discovering ourselves- how we relate and project onto certain characters, and what this means about our own identity and experiences.

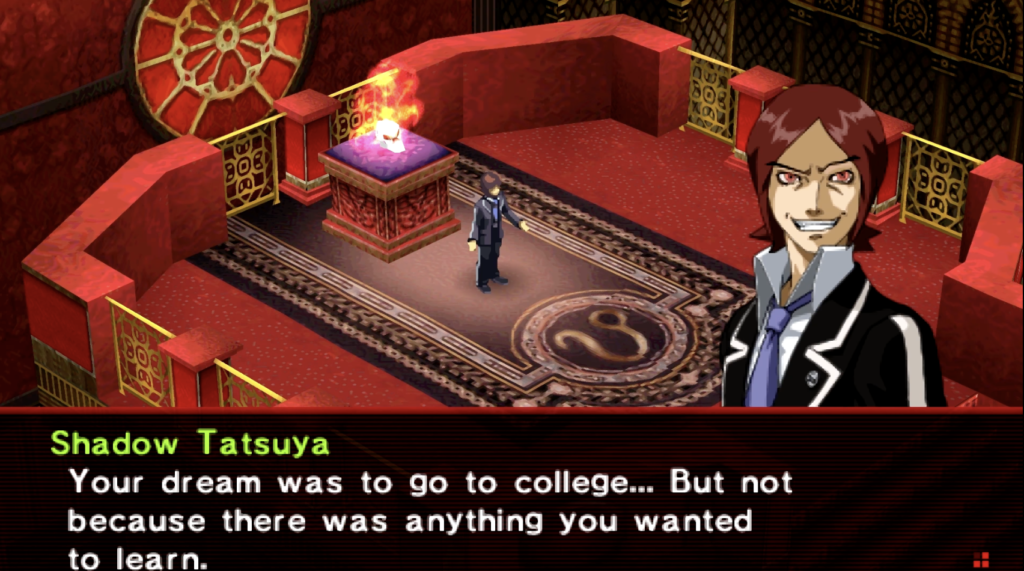

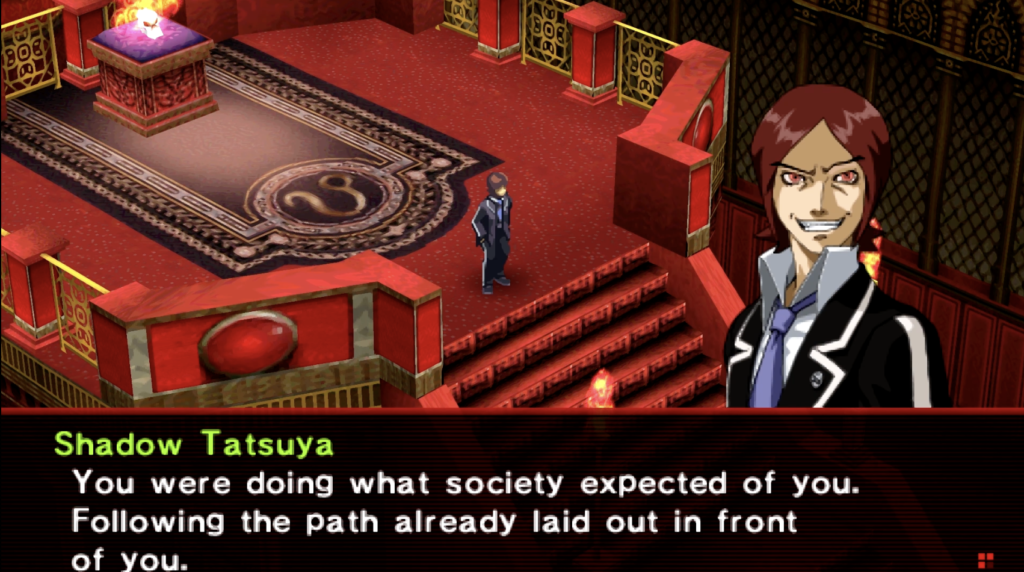

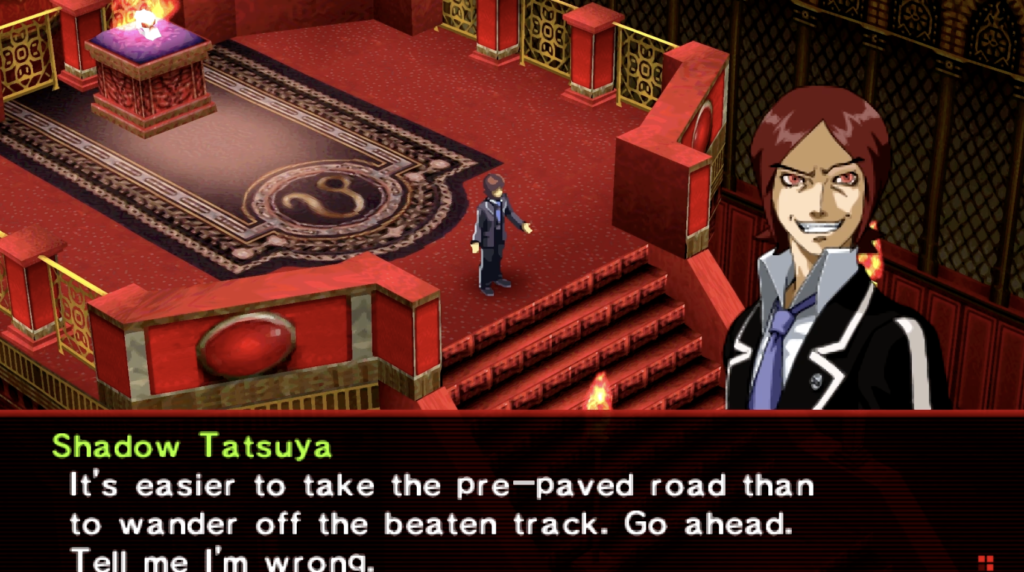

Later in Persona 2: Innocent Sin, Tatsuya is faced with his shadow self, a doppelganger of himself who interrogates the choices made at the beginning of the game. As it was the first scene, I answered the question about his future plans as I think any player would- with my own answers, as I did not know Tatsuya yet, and what he would most likely say. Based on these answers, however, his shadow will interrogate the payer.

It’s here that I believe Persona 2: Innocent Sin truly embodies the strengths of its genre, if it is a little on-the-nose. The player is assuming the role of Tatsuya Suou, and these questions are targeted towards him- about the pressure for him to follow in the footsteps of his beloved older brother, or his inability to express himself. Yet, these are also common anxieties incoming college students have, particularly while choosing majors- fundamentally, the game forces one to use the role of Tatsuya as a lens to interrogate their own plans and beliefs. Ultimately, playing the role of Tatsuya Suou forced me to think, and in this way, it taught me something valuable- about the world, the human experience, or even just myself.