Dripping with postmodern irony, The Stanley Parable’s avant-garde social critique examines the medium of video games with a humorous sincerity rarely seen in contemporary titles. Released independently, the narrative considers various formal and cultural conventions through a wildly variable set of situations and circumstances. Exploring the notion of free-will, The Stanley Parable is as self-aware and conceptually unbound as any game I’ve played, questioning how a video game can truly utilise and transcend its medium. I could illustrate the importance of The Stanley Parable through any number of its many, many endings. However, I’d like to briefly discuss the “skip-button ending.”

In this ending, found on the game’s Ultra Deluxe Edition, The Narrator guides Stanley to the Memory Zone, retreating from the “disappointing” content of the game thus far. Preserved here, amongst the positive reviews for the original game, Stanley stumbles upon a forgotten area, hiding a slew of negative reviews and critiques. “You constantly have to stop doing anything so the narrator can catch up with his long-winded explanations of what’s happening. I wish there was a skip button” writes Steam user Cookie9. Dejected, The Narrator implements this mechanic, encouraging you to press skip whenever you feel he’s gone on for too long. Cookie9 is as irrelevant as his complaint is innocuous, however this review, alongside The Narrator’s vulnerability, damns him and Stanley to an ending of true existential terror. After hours in his company, the game has nurtured a genuine relationship with The Narrator. We’ve heard all of his thoughts, aspirations, frustrations, and insecurities, which makes what’s about to happen next all the more painful.

Inevitably, we’re incentivised to press the button. However, after our third skip, The Narrator informs us that not only did Stanley skip the last 35-40 minutes but the door that they entered through has also inexplicably disappeared. Trapped in this room, the time jumps begin to incrementally increase as we repeatedly push the skip-button. Left alone, The Narrator’s psyche beings to slowly unravel until he is left pleading with Stanley to stay with him, to keep him company. After our sixth skip, The Narrator solemnly describes his year in dark isolation, a realisation made all the more significant by the fact that we, as the player, chose to press that skip-button and leave him alone. Of course, we are only given the illusion of choice, nothing would actually change if we elected to stay with The Narrator but there’s no way to tell him that.

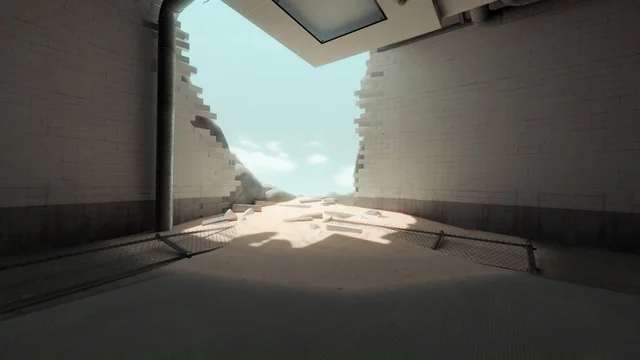

After our eleventh skip, we hear The Narrator endlessly repeating “the end is never the end” before lapsing into perpetual silence. This is the last we’ll ever hear from him. The next couple of skips presumably span millions of years as the room gradually decays, caves in, and is transformed into a serene area of calming plant life and sunshine. I’d love to expound on the strange existential comfort of this room, somewhere close to the end of time, but inevitably we press the button again and lose it all. Over the final two skips we’re plunged back into darkness before the walls finally collapse, breaking the skip-button in the process. We climb out into a flat, endless desert, truly alone at the end of time. We begin to wander out and the game resets. I don’t know what to feel. I thought this game was supposed to be about working in an office…

I like your detailed description of the “Skip Button Ending.” This also reminds me of the concept of “game time.” In non-real time games, we as players experience game time very differently from real time. Even in real-time games, we are given the privilege to pause the game or leave the game at any time. “Skip button” magnifies the disparity between player’s time and the game’s narrator’s time. The player becomes the god-like character that is immune to game time, while the narrator is trapped in game time and the game decayes with accelerated game time.

I think that existentialist is the right word to describe this ending. Here, the idea that perception by and interaction with a conscious object is crucial to one’s grasp of meaning is vividly illustrated, not only through the narrator’s breaking-down, but also through the existentialist feelings of void and solitude that the game–with the decaying scenery and the disappearance of the narrator–renders the players with in the end. As such, I agree that this ending has a particularly powerful effect on the player. I, for one, was thoroughly mesmerized.