In 1943, Jean-Paul Sartre writes his book Being and Nothing: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology where he develops the philosophical basis to support his theories of existentialism, which included topics such as the existence of nothing, free will, consciousness, and perception. In the perception section, Sartre introduces a concept known as le regard, or “the gaze.” Le regard has the uncanny ability to create a power difference between a person and the person they are gazing at. Sartre states: “by their presence–most forcibly, by looking into your eyes–other people compel you to realize that you are an object for them.”

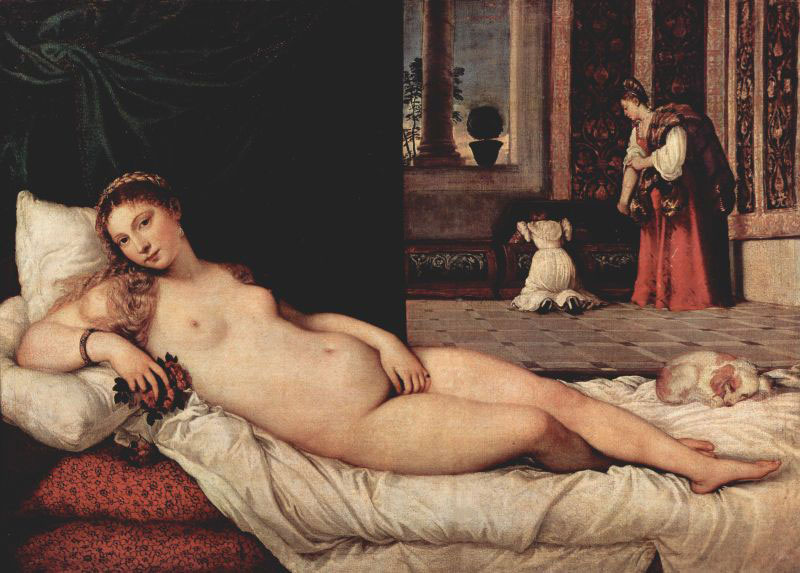

Thirty-two years later, Laura Mulvey took the concept of le regard and applied it to cinema in order to critique traditional representations of women in media. It is from her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” that the term male gaze, the framing of women and the world as sexual objects in the perspective of a heterosexual man for the viewing pleasure of male heterosexual viewers, was constructed. Thus, it can be concluded that the male gaze functions the same as male fantasies–typically sexual, but can also be romantic or platonic–regarding women. The concept was then easily applied to other forms of media, such as literature, artwork, and in the rise of technology, video games.

The Male Gaze in Galatea

Galatea is an interactive fiction game based on the Pygmalion myth from Ovid’s The Metamorphoses. The myth, in whole, is a male fantasy: Pygmalion, a sculptor from Cyprus, carves his ideal woman in ivory–as all other “real” women contained too many faults–and falls in love with her. He prays to the goddess Venus to grant him a wife similar to his statue and, surprise, surprise, with divine power, she makes the statue come to life, and they get married.

Instead of playing as Pygmalion, the player adopts the role of an art critic who has come to Galatea’s gallery to write a review of the gallery as a whole. The entire premise of the game is that the player types text commands into the text bar in hopes of progressing the story. Thus, in a sense, the player themselves, regardless of their gender, occupies the role of Pygmalion.

What do I mean by this? In Galatea, there are around 70 possible endings. With each typed command, you get closer and closer to achieving a certain ending. So, to continue the metaphor, each command is similar to the chisel that was used to create Galatea’s likeness. The more the player continues to talk with Galatea, the more text commands they type in, the more they guide her responses and the conversation, the player creates their “ideal” Galatea in order to achieve a certain ending. The player becomes Galatea’s artist, consequently falling into the same male fantasy that overtook Pygmalion: the desire to have their desires come true.

If you want Galatea to be a woman that eats cheese, you can make her be a woman that eats cheese. If you want Galatea to become your lover, she will eventually become your lover if you go through the correct motions. If you want Galatea to leave, you can make it possible for her to do so. There are endless possibilities, and the formation of her character is entirely up to the desires and fantasies of the pseudo-Pygmalion player.

Galatea is obviously not the only game that uses the male gaze and/or male fantasies in their narratives; Galatea however is probably one of the few games that incorporates the player in the creation of the male gaze. It brings up an interesting question of the functionality of the male gaze and why the male gaze is used. What is gained in the portrayal of women in this matter? Can men or male characters also be victims to the male gaze? Is the female gaze (similar to the male gaze, but directed towards women instead) applicable to video games as well?

Bibliography

Stack, George J; Plant, Robert W (1982). “The Phenomenon of “The Look””. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 42 (3): 359. doi:10.2307/2107492. JSTOR 2107492.

Mulvey, Laura (2009), “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, in Mulvey, Laura (ed.), Visual and other pleasures (2nd ed.), Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire England New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 14–30, ISBN9780230576469. Pdf via Amherst College. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

Ovid. Metamorphoses Trans. Rolfe Humphries. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1961. 241-43.

I think your post says what a lot of us have on our minds, and does a good job of working through the evolution of the theory in the literature that deals with voyeurism, the male gaze, and power imbalance inherit in the objectification that can occur with the understanding that while you can be a subject, you can also be an object. I will say, however, that I wonder how the medium of a playable game twists the meaning or usage of “the gaze” we’re discussing in Galatea. In a film, there isn’t any interaction. No typing. No interaction. You simply watch and observe. A game ,however, presupposes play in some form. How does the action inherit in play manipulate how voyeurism and the male gaze functions in a narrative game like this, if it does at all?

I also appreciate how the post presents the theory of the male gaze in a clear and well-constructed way. And your questions are very interesting! I would say that playing expands the possibility of the male gaze in its 2 oppositions. It can strengthen the male gaze to some extent by offering more detailed looking, vivid interaction, and voyeuristic descriptions. But with the agency given, players can also choose to subvert the male gaze to some extent, by looking away, making her leave, etc. Instead of sitting in front of the screen and being forced to accept the way the director wants you to gaze at a female, the audience can actually pause and think, maybe even change perspectives. In this sense, there might be some space available for reflecting on the gaze in the games.

Helen’s responses assumes an interesting pre-requisite to subvert the male gaze, namely the player’s subversion of their identification with the avatar. Given that the game designer intentionally puts players in Pygmalion’s position and gives them the power of male gaze, players need to consciously acknowledge the avatar’s “male gaze” and take actions to resist what is offered and contradict the intention of the game designer. In this case, I agree to what Helen said: in films, viewers are passive observers without any power to change their own gaze, even if they acknowledge the power of male gaze the protagonist has and do not want to relate to it– there is nothing they can do even if they do not identify with the protagonists. In games, however, people tend to have more agency: if they do not want the male gaze, they just end the game. We have the freedom to relate or not to relate to the avatar, and we have the agency to take actions accordingly. Then there is this question of identification that we touched on during the class: how do video games make us relate to the avatar? How do games prevent the situation where we fail to relate to the characters in the game and act against the will of the game from happening?

I think your post really dives deep into the design of this game. When I played Galatea, I gave up after typing several commands and receiving answers that do not make sense. I never get to the ending. However, from your post I get to know the philosophical meaning behind this game which seems to make no sense and not very player-friendly.

I really enjoyed reading your post, especially as it made me consider how the idea of “gaze” can be applied across different media. The idea of gaze is something that is very clear when we are watching movies, for example, since the camera angles serve as the sort of “eyes” that the viewer has no choice but to see through. However, in Galatea, the player has various options of how they want to interact with Galatea herself, asserting some sense of choice in the type of gaze that they inhabit. Additionally, Galatea is a text-based game, so it is left up to the viewer to imagine the scenes in their mind’s eye; how might this affect the experience of gaze? Does the player have enough agency to view Galatea in their own manner or are the narration and dialogue enough to restrict the player to one “view” of the game?

I really enjoyed reading your post! I think the idea of the male gaze becomes interestingly complicated by the interactivity of video games in ways other commenters have already mentioned. However, I really bought into your argument that in this case, the game’s interactivity strengthens certain aspects of t he male gaze by allowing the player to construct their fantasy woman. I’m interested in considering though how the game developer shapes this ability and whether these limitations are consequential. Yes, as the player you have a variety of possible ways to interact with Galatea and you can build your relationship. generally to your preference. However, your options are still limited, and there are some things you can’t do. How does what you can’t do affect the presence of the male gaze in the game?

The idea of the player “chiseling” away at Galatea is really interesting! One thing I would wonder about that might complicate this, though, is how to incorporate the endings in which Galatea becomes actively hostile against the player–or, more generally, the fact that players don’t know exactly how each ending is going to play out until they’ve arrived at that ending. Galatea, the game, can be a bit obtuse sometimes, and I think that that complicates the notion of chiseling a way to create a character of your desire. Do we judge games based on how they’re played through the first time around, with the player unaware of consequences, or do we judge them knowing everything that happens–or every way a player could go back and replay it–in retrospect? I’m not 100% sure of the answer to this, but I’m glad your post got me thinking about these things!

I think this is an interesting perspective on the game, one that I was thinking myself. Through your gameplay, because of all your options, I feel like the player and therefore the artist has a lot of control over how Galatea reacts and acts in general.

What I think is also interesting is how much this game leaves up to the imagination. Although there is technically a limited amount of options, there usually is a way to do exactly what you’re thinking, whether that be taking Galatea with you, or falling in love with her. I sometimes felt frustrated with the limited options which I feel could simulate how the artist would feel with sometimes getting limited reactions from Galatea. I haven’t been through all the endings, but in those that I have seen, it seems a Galatea is always serving the player, and never really serves herself.

Another thing I wanted to mention that I find interesting is how the male gaze seems to easily be used in all types of media, whether that be in books, cinema, or video games. It is something in real life that can be abused. Even the photo of Galatea gave me an eery feeling of Galatea being almost stalked in a sense.

I really like your ideas in this post! I am studying the Metamorphoses of Ovid for my HUM class right now, and we also talked a lot about the male gaze in that class. In Ovid’s original text, Pygmalion is always the subject of his sentences, while Galatea is always the object. This shows Galatea’s lack of agency and objectification. I definitely agree with you that the player is taking on the role of Pygmalion. And also what I found super interesting is how the setting of this game takes place after the ending of the original story in Ovid, acting like a sequel. I did not expect to find that after turning Galatea into a real person, Pygmalion asked her to turn back into a statue and eventually left her. I think that Emily Short is trying to suggest the idea that many men expect their girls to be exactly how they imagined in their 2D fantasies. Similarly, in many of the endings, the player gets kind of bored after digging up a lot of information about Galatea, and remembers that they have something else to do, and then leaves. This is the exact same thing that Pygmalion did to Galatea. This shows that when men find out too much about a woman, or when a woman has too much agency, she gets “boring” and eventually is abandoned.