After playing DDLC and TING, and even Save The Date, I started to think about the similarities between these games and frame narratives in fictional literature, film, and television. Obviously, games can employ familiar frame narrative structures (where a narrative is told within a broader one), and narratives told through other media can take on meta elements apparent in the aforementioned games, but I found it interesting that these games, in a way, do both. DDLC and TING each present a narrative in which one of the characters is not only aware of the existence of the game, but comes to control the game space (a sort of character-narrator) – Monika and Game respectively. In DDLC, this frame dissolves by the end – at which point there is no inner narrative/game, and the player is restricted to interaction with Monika. But at different points in both of these games, the player’s actions are observed and commented on by each game’s respective character-narrator, establishing that there are games within these games.

One of the most interesting things to consider, with this in mind, is where the frame breaks down in DDLC and TING – are there any moments, screens, or services within the games that exist between the two frames or outside of both of them? We talked at length in class about what elements of a game exist within the diegesis (the world within the narrative) and what elements exist outside of it – common examples include the audio and visual settings of a game, often the game’s title, and corporate logos. In DDLC and TING however, the game world is purportedly controlled by one of the characters. Many of these elements thus fall within the diegesis of this outer frame but outside of the inner one – in DDLC, Monika not only alters the menu options (clicking on “main menu” does nothing, and previous player saves are deleted) but comments on player actions that are not usually considered game mechanics – quitting the game for instance. In TING, Game is aware of the player’s ability to interact and, like Monika in DDLC, comments on actions like quitting the game and even selecting a language.

Despite the seeming omniscience of these character-narrators though, they still exist within a broader narrative. This might be an obvious point, but I think it is interesting to consider what exactly makes this the case – what exactly rebuilds the fourth wall.

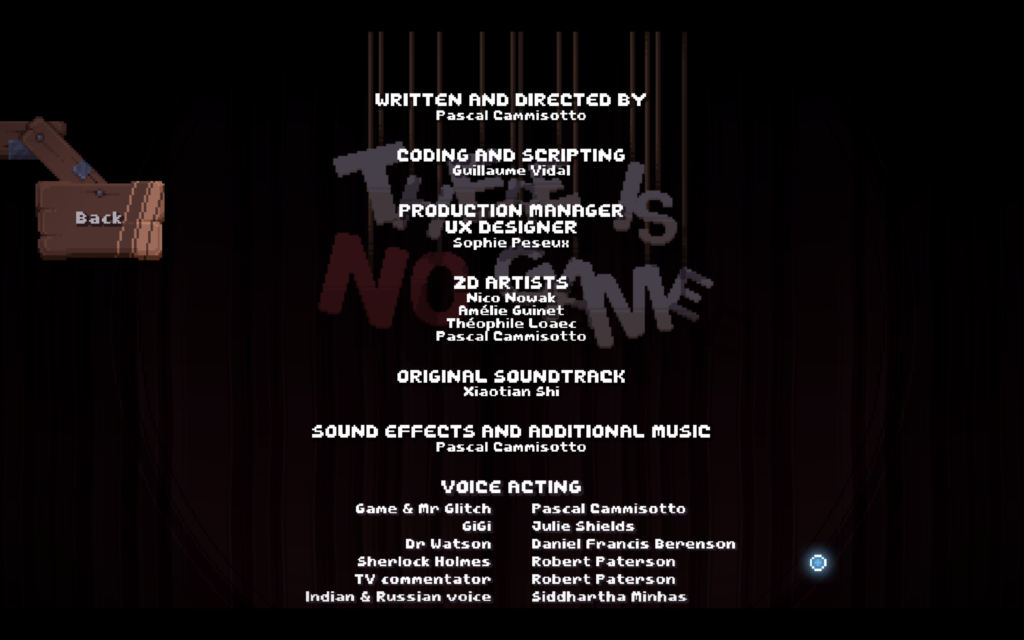

In DDLC, I would argue that one example of this is the help page that opens in a player’s browser when the “help” option in the menu is selected. Although one might argue that this is still within the purview of Monika, the existence of a section that allows the user/player to delete save data and start the game “completely over” – this is certainly not something that Monika would want. When playing TING, the player is able to view the game’s credits in which the contributors to the game are listed without being prefaced by an introduction that maintains continuity (as “Not a game by Draw Me A Pixel” does). This is also apparent in the representation of fictional “character files” that Monika deletes in DDLC, and a fictional desktop for Game in TING.