How to Fail Gone Home

There was a discussion in class on Tuesday (Oct. 12th) about the overall nature of Gone Home, and in this discussion there were interesting ideas regarding whether Gone Home was a game or simply a piece of interactive fiction. If I recall correctly, one of the points made against Gone Home being a game was the fact that there was no failure state. The gameplay consists of the player walking around the mansion looking at clues and listen to recordings. There is no way to “lose” in the traditional sense. There aren’t any monsters lurking around the house that try to kill the player, and there aren’t any possible endings that the player could’ve missed. Compared to in Soma where there are various monsters that can attack the player, there is no way for the player to even receive damage in Gone Home. Playing it is much less active experience, almost like walking through a museum, but is still active nonetheless. But I would argue that there is a failure state.

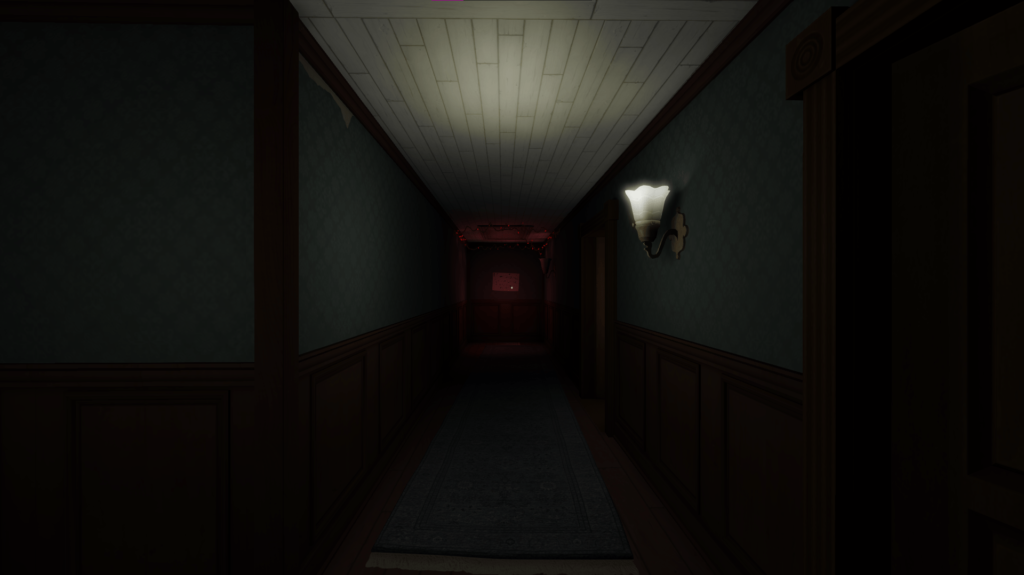

In order to make this claim, I first have to make a confession: I am terrible with horror. If I get even the sense that something bad will happen, most of the time I refuse to continue. I couldn’t finish Gone Home. I stopped a little while after seeing the red lights around the attic door for the first time. If I were to guess why that aspect of the game in particular caused me to stop, I would say it was because I was afraid of the truth more than any potential jumpscares. Seeing those red lights around the attic illuminating the dark hallway screamed “DANGER,” and the note on the attic that said “Do not enter if red lights are on!” felt very eerie. I started fearing the worst possible outcome for Sam, who had seemed to always be a disappointment to the family based on the clues left behind.

The Failure State

In a way, this is sort of the goal of the horror in Gone Home. The game drops the player into an unfamiliar house, and they are given the sense that something bad has happened, with Sam’s note left on the front door. It feels like the game is intentionally trying to cause the player to fear the worst, as obstacles towards finding out the truth. Frequent clues left behind about Sam not living up to her parents’ expectation, the red dye spill that is presumably blood until the audio file starts playing, and then general emptiness of a house whose family was presumably anticipating their daughter’s return all contribute to this spooky atmosphere. The player’s character, the favorite sibling, has been gone for a while, and as a core part of the family, it feels like Kaitlin Greenbriar, controlled by the character, is obligated to figure out what happened in the time she was away from home.

It is in this way that I feel like I managed to reach the failure state of Gone Home: I was unable to fulfill Kaitlin’s obligation to uncover the truth, and because of it, it feels like diagetically, Kaitlin will never learn what happened to her sister. Facing the truth is not supposed to be easy, and although the truth was not nearly as grim as I had imagined, failure to attain it by playing the game myself feels like missing the end goal of the game: the failure state.

One might say that this notion of failure state applies to any game with an established end goal. If I refuse to finish Super Mario Bros., Mario will never rescue Princess Peach. If I refuse to finish what I set out to do in the first place, the story will remain incomplete. However where the difference lies with Gone Home, and perhaps other horror games as well is that horror itself is such an intense medium to experience. My emotional engagement with the game is partly what defines the horror genre. As such, not being able to handle the intensity of a horror game feels more like a mechanic rather than faulty software or a matter of personal preference, especially since my particular feelings of horror align with what seems to be intended by the game.

So then why would a game be designed such that some players will stop playing? Similarly to how it’s possible for players to lose in a tutorial level, my example of a failure state seems to be something that is highly uncommon, but can still happen, so it doesn’t feel like the game is necessarily designed for me to quit, although there could be an argument made about how quitting is a failure state for horror games in general.

I really loved this post, and I think that is in part due to how much I relate to it. I, too, am someone who struggles a lot with horror, especially in games (SOMA, despite being criticized by games journalists for not being scary enough was quite the impossible feat), so this week posed some challenges. I actually played Gone Home years before, and when I revisited it, I suddenly remembered the horror fake out elements. Thinking back, I remember almost dropping the game until I looked up a spoiler that exposed there were no jumpscares or overt horror segments.

However, does the fact that I completely forgot about these fake-out parts to this game say anything about this part of Gone Home? Looking deeper, these horror parts seem to do more to lead the player astray, making them think this game is something its not. Is this a good thing? Would Gone Home have the playerbase it has without its initial misconceptions? Did the developers feel the need to introduce these more standard elements because they were breaking new ground in terms of untraditional games?

These are all questions that your post has inspired. Really great work — you made something I completely forgot about into something that I can’t stop thinking about!

This is a great point, and I think, when defining what a game’s failure state is, an important thing to consider is what defines its success state. I find that, at its most basic level, Gone Home is a mystery game, where the player must look for clues and piece together evidence. Success in this regard would be to uncover what has transpired. As such, the failure state specifically is not figuring out the mystery and stopping, even moreso than quitting any game could be considered a failure state.

The player does not play the protagonist of the story (Sam), but instead an almost “detective” like figure. For example, in a detective story, the detective does not fail by getting killed (while the person they’re investigating might), but instead by not being able to solve the case. I think this connects directly to your argument that Gone Home’s failure state of quitting is different from simply quitting other games.