Playing into the irony of digital productions – metaproceduralism is noted by Fest to be a powerful tool for getting players to look more introspectively towards the algorithmic and procedural actions that they take or interact with. This metaprodural content often has a critical and intentional purpose that changes game to game as the themes and atmospheres differ. Stanley Parable may use it to get you to think differently about personal will, desire, or purpose in corporate environments, or the adherence to big tech’s seeming omnipresence. Doki Doki Literature Club’s use could be more aimed towards challenging your pre-existing views towards matters of significance in dating-sim games or relationships more generally speaking. The usage of this type of irony in these cases seems to carry a critical focus as we can directly apply the insight they provide to big-picture problems or ideas that we think about in the time we’re not playing games.

In comparison to examples of non-critical metairony, where the intention is typically just to garner a quick laugh or make note of itself, does critical irony always prove to be more provocative? I believe there are still critical concepts that indirectly come about by the use of non-critical metaproceduralism. Although it might initially be seen as just a comedic gag based on self-reference, these instances have the potential to snap players out of their immersion in a way that more critical forms of ironies wouldn’t. It’s not like these forms of irony are mutually exclusive or cannot occur within the same game, but I want to make note of the way in which “simple” self-references can still carry a lot of emotional or cerebral weight.

”

“I The Game, Am Upset With You, the Player”

Why would a game or the characters within it express that they are not having a great time to you the player? Well, you may be going on a bit of a power trip. Just because you’ve been given the privilege to live vicariously through an invincible/super powerful/charming character doesn’t mean you should let it go to your head.

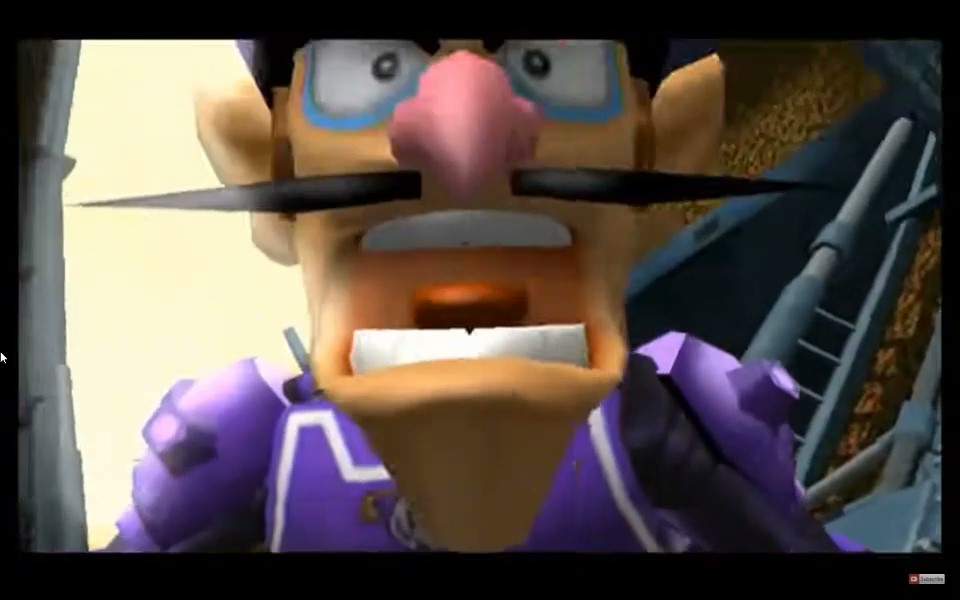

This idea comes across as Resetti asks you to treat him with some respect and not as an object to be used then ignored.

It also comes up in There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension where you continuously ignore Game’s wishes and invade their personal space. They both tell you explicitly that you are overstepping bounds, but also get in the way of your gameplay via large chat bubbles and safe-locked buttons. This may be a simple humor point at first, but further reflection can get the player to think about how their actions impact players in the virtual world. What may be good fun and games to us as players certainly is pretty real to them. In this way, we can be likened to war generals treating soldiers on a battlefield like pawns in a chess game. Sans in Undertale definitely makes you conscious of this fact as he informs you of exp and lv meaning execution points and level of violence respectively. These meta concepts are pretty explicitly being applied to phenomena that are just in the games, not immediately transferable to real life, but they can find a way of being important to real-life interactions nonetheless.

“Maybe We Shouldn’t Talk About “That” Here”

Sometimes we should not talk about the things that immediately come to mind. Like in the case that you would want to avoid copyright complications with the misuse of creative content. The interaction between the two characters in the clip above is aloof but can be a genuinely good thing to hold in mind with actual conversational interactions. When certain events or situations make it inappropriate to bring something distracting up that is unrelated to the current topic, this moment makes note of that. Or when you unintentionally mention something that can be hurtful or a sore topic for some, this moment also can be used to think more critically of that position.

Games convey messages about their world that translate to ours in more ways than the encompassing messages that are more explicitly given. Through mundane comments and interactions, they enable us to be emotional or witty, simply by acknowledging us in those ways.

Honorable Mention – Just Something I Wanted to Talk About Removed from the Main Point

“Your Save Data is Gone”

It is pretty scary when a game character just up and deletes your save, or pretends to. It feels like a pretty heavy loss to have so many hours just gone, and seemingly out of your control. It’s a loss of agency in a pretty different way to horror games where you often have the catharsis of the danger being behind a screen and not actually affecting your physical materiality. This, by contrast, is a direct assault on the player’s time investment and connection to what they’ve achieved within the game.

The reference to Resetti really resonated with me. Especially in Animal Crossing: New Leaf where the player has much more perceived power, becoming the mayor of their own town, getting scolded by Resetti for resetting does seem to be a method for keeping the player in their place. Although the fourth wall break isn’t complex in nature, it does have a greater implication than simply humor. I’m not sure if this was intended by the game developers, but either way, it certainly has this effect.

I think this is an interesting point to make about subtle moments of irony. The way I see non-critical irony is like a parenthetical in a piece of text; it’s a short moment where the author/game designer can speak to the reader/player directly, aside from the reading/video game experience. Novels that are purely fiction are unlikely to speak to the reader directly on, in the same way that straightforward adventure games or role-playing games are unlikely to have these small meta moments.