We’ve discussed Super Mario Bro’s first level/screen in depth–particularly its elegant disregard for clear-cut tutorials. Since then, I’ve come to not only think back on other game intros that I found compelling (like The Elder Scrolls prisoner intros) but also approach the games we are playing with a specific eye to their first few minutes. To this end, I would say that the first ten minutes of Bioshock (2007) are exemplary in immersing the player into a game’s key mechanics and themes, while also utilizing non-navigable spaces as moments of rich storytelling.

The first words you hear–“They told me, ‘Son you’re special’”–is not only a literal case of main character syndrome, but it also provides the foreshadowing groundwork that builds into the ultimate plot twist at the end of the game. The lack of player-led movement is crucial to consider in the context of Bioshock, as it is not a guarantee that a game will begin with no navigation of the world in favor of a cut scene. Still, with its cinematic start and title sequence, the game then literally plunges the player into the two main forces it will encounter in the following playthrough–water and fire. I would say the object choice of pearls in a handbag says a lot about the later themes of drowned glamor that Rapture encapsulates. At this point, there are little few instructions on what to do, and per Mark JP Wolf’s “Theorizing Navigable Space in Video Games”, the spatial cell at first appears to quite literally be the entire Atlantic Ocean (Wolf 22).

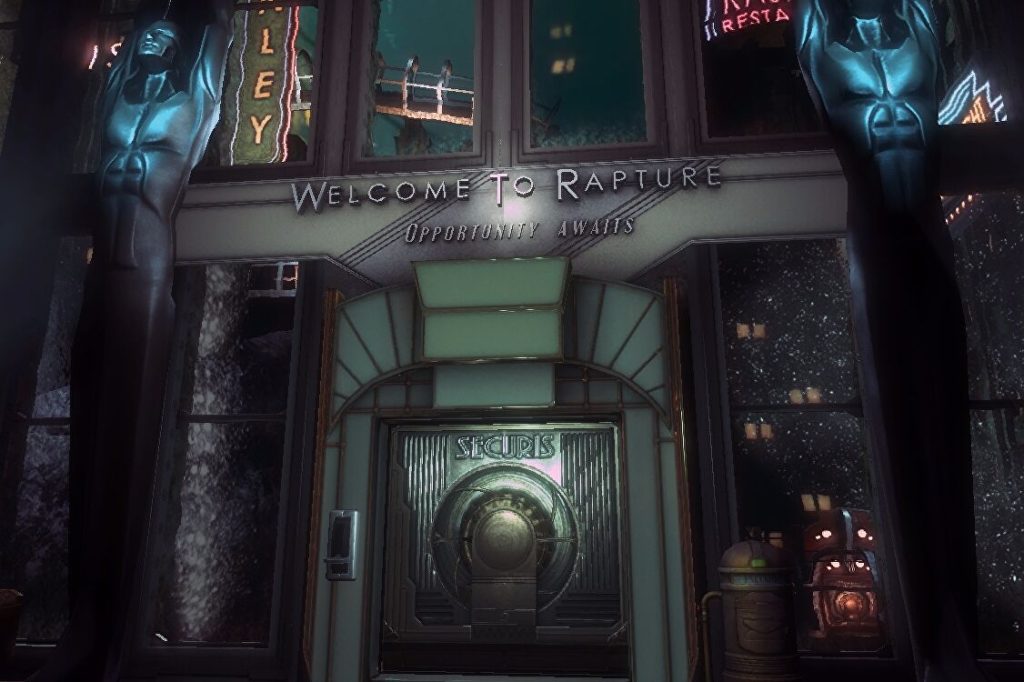

That is until you find your way to the lighthouse, in which the first sight of civilization immediately introduces the player to Rapture’s Art Deco iconography. Thinking along with Henry Jenkins’ frameworks of narrative in “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” such use of architecturally aesthetic serves to evoke narratives of grandeur and splendor known for the eras in which cities leaned into their geometrics. The first connection you pass through is a golden door that’s been left cracked open. As it closes behind you and the lights turn on, you realize that although the world itself is navigable at your own pace, there are enacted story points that you will be led into–and the lack of agency will itself become a central focal point to the draw of the narrative. Bioshock’s use of its environment to invoke and enact specific narratives can do so quite explicitly, as its narrative payoff hinges on the player buying into said enacted narrative so that its plot twist can be all the more rewarding. “No Gods or Kings, ONLY MAN” thus becomes a key point of irony that the game hinges on the player keeping in their minds throughout their navigation of Rapture.

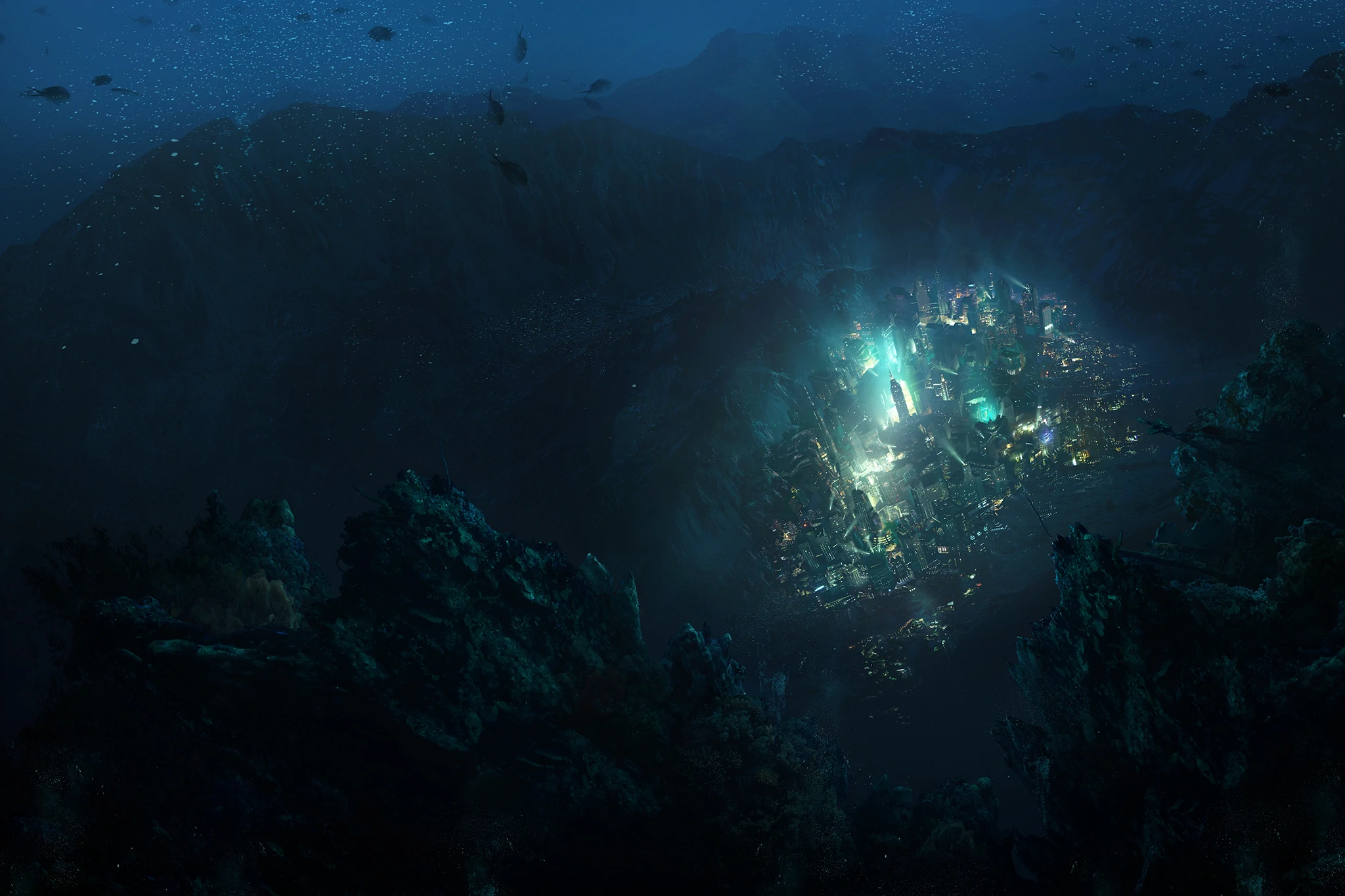

Finally, the lighthouse introduces bit by bit what controls are to the gameplay ahead. Leading the player into the Bathysphere prompts interactions with objects, and the “track-like” descent into the city provides another immersion into the graphic patterns and exposition that are crucial to enact early on. The view outside of the window is a space outside of the player’s opportunity to explore, yet it is a great form of literal submersion into world-making. As the Bathysphere tracks into the first Rapture building, the game also introduces the main antagonists that will come up throughout the narrative–a Big Daddy is seen in a tunnel, Andrew Ryan leads the narration, and a Splicer delivers the first violent death scene (aside from the passengers of the plane). The biggest exception to the introduction’s ability to ‘show and not tell’ is the loading screen that appears before the sphere docks, as the screen does include instructional text on the bottom part of the screen. Nevertheless, I would argue that the immersion of the following last minutes of the introduction still put the player at the helm of finding the key controls through exploration rather than explicit instruction.

Indeed, as the Splicer kills Johnny, the game crucially introduces the UI with health and EVE meters, the New Goal pop-up, Atlas’ voice for the first time, and the motif of horror. For this latter point, it is quite masterful how the narrative swiftly moves you from the awe-inspiring shots of Rapture to the terrifying sight–through a foggy glass–of a Splicer trying to break into the bathysphere as the lights flicker. While the game has yet required the player to shoot by the time the bathysphere opens, Bioshock’s introductory level has established its fundamental narrative points and submerged the player into its Rapture.

I love how you connect the atmospheric storytelling within Bioshock and then extrapolating it to how it immerses the player preemptively.Your points are coupled beautifully with the photos you provided, I think they added an extra layer of depth to your blog post because it allows reader to connect and visualize the points you are making. Enjoyable read!

I love your step-by-step analysis of the sense of immersion developing throughout the first few minutes of the game. You also mention breaks in this immersion, at least with the mention of the loading screens, although this reminds me of other breaks such as the pause/objective menu and the difficulty selection in the beginning. You say that this is a deviation from the “show not tell” aspect of the game, but I think that it still actually contributes to the player immersion. When I played the game, I was at first confused by these moments where the game directly addressed the player to tell them about the game, because it would seem that this would break the immersion into the game world. However, I realized that these moments actually made me feel as though the main difficulty of the game should not be in things like navigation or shooting, which it was giving me tips on — instead, it felt like the difficulty was from the horror of the environment and the story I had to go through. By making the game mechanically easier, it felt to me like the psychological difficulty and terror of the game was made a greater focus, and so even though the “immersion” into the world had been broken by addressing the player, I actually felt more immersed into the emotional themes of the game. I definitely agree with you that the start of the game feels very natural in its immersive construction of the atmosphere, but I also think that even the breaks from the world of the game are so well-constructed that they contribute to the immersion rather than disrupt it.

On that subject of prompting players to explore and interact, I think that opening sequence before you enter Rapture is beautifully done, especially with the ending twist in mind. There is no clear instruction–like you quoted, the play space is literally the entire ocean–but player instincts lead us to go to the island, which is reasonable, but then to delve into this mysterious building with propaganda (as labelled by the game itself) and the bathysphere, which neither the player nor their avatar knows anything about. Yet, the player enters it because that’s what’s presented; all they’ve been given is a space, and of course it makes sense to explore, even though logically there’s no reason to head down the sphere and into Rapture. A reasonable person would have simply waited on the island for rescue, perhaps inside the ‘lighthouse’–but when people play this opening, they’re not reasonable–because the space they’ve been put in is leading them there, almost without question or consent.

I really love how well you strung your argument together. Not only is the writing easy to follow but the structure of the blog is very logical. What I wished you touched on more is the dichotomy between being told that we are the chosen one -very explicitly- and then being thrust into a world that entices exploration as opposed to instruction. What does it say about the game to instruct us narratively but give us physical freedom? Especially when the rest of the game involves fairly strict physical paths but narrative choice.

Your argument is really well constructed. I love your analysis of navigable space during the introductory sequence. To add on to this, the lighthouse also serves as an evocative space. In the third installment of the franchise, BioShock Infinite returns to an opening scene with a lighthouse, except instead of going down and eventually reaching a bathysphere that will take you down even farther, you go up until you reach a totally normal chair that will encase you in an upward-travelling vessel. I think it’s really cool that games create evocative spaces for sequels, and it just goes to show how important evocative spaces are in storytellling.

Your point on non-navigable space informing storytelling seemed especially apt to me. From the Bathysphere, we witness Rapture in all its impossible glory: an actual city at the bottom of the ocean, replete with bold contradiction that the art deco architecture complements. In that first moment, the degree of submersion is so well-tuned that it actually feels like we’re entering a city that we’re going to explore, though most of what we see is non-navigable. It doesn’t matter that the actual gameplay takes place in essentially a linear series of maps (basically sophisticated dungeons, in my opinion); the immersion carries so well from that first moment and is bolstered by additional moments of presentation of non-navigable space (like a window or porthole). Very inspiring post!

This is a super interesting post! The idea of Rapture being “welcoming” despite the pseudo-horror elements of the game seemed a bit farfetched to me at first, but you explained your argument really well. I feel like the game definitely does a good job of “welcoming” you to the mechanics while also developing a sense of unease through the setting and atmosphere. I think a continuation of your argument could go into detail about how navigability in the game could impact the player’s decisions on exploration (e.g. running into every barrier in hopes of finding secrets vs making assumptions and going to specific areas to continue the narrative). All in all — nice work on this one! :>

I like your detailed analysis of how the scenes create a sense of immersion. In Bioshock, the navigable spaces with embedded narratives arguably do a better job of immersing the player than the opening movie cut scene. Through synchronizing the player’s control and the avatar’s movement, the player subconsciously identifies more with the avatar and the world of Rapture.

I also like how the introduction in Bioshock is very limited as to what the player can do. Which I think you touched upon with the fact that the game establishes all the narrative points before the player can even shoot a gun. But I find this limited ability to interact with things to be rather interesting. All the player can do is move and look around. The player is persuaded to think and take in only the narrative points of the game. There is no swimming up and down mechanic, no way to take damage and die (I tried to press against the burning debris), and if I remember correctly you only interact with the lever to enter the bathosphere or maybe the door. But other than those two points the game only really begins, that is the feeling of. danger and having a genuine threat, after exiting the bathosphre. So overall I think these decisions were intentional and the introduction of Bishock is definitely one worth examining because it establishes the narrative rather effectively.