In her Ted Talk “The danger of a single story”, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about just that: a story focused on only one aspect of, one perspective on a people or a narrative, and how that breeds stereotyping and reduces that people to a single trait or concept, losing everything else in the process.

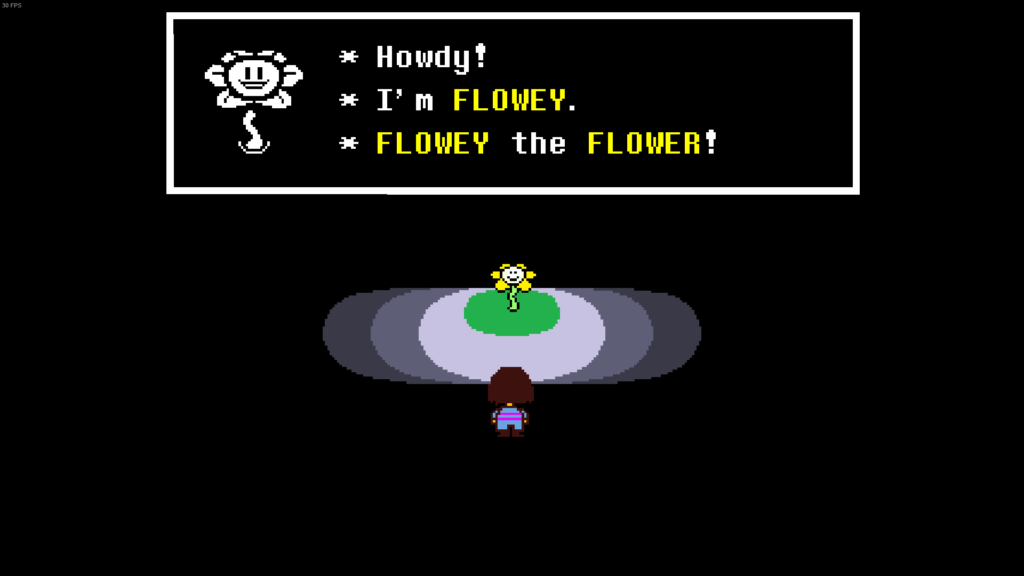

Undertale is not a single story. Typically in a game, enemies are just that—enemies—but in Undertale, even though they’re called “monsters”, they exist as more. They are a people, and each individual monster is a person, with their own personality. From the player’s first encounter, Flowey makes it clear that more belies this world than shows on the surface–he is not just a tutorial, as the game and his dialogue structurally suggest at first, and he’s not just a happy little flower as his sprite and music might imply. He’s more than an enemy; he’s an independent actor with his own story and goals.

This concept continues through the game’s most distinctive combat mechanic, the “SPARE” button, which usually only works after the player uses the appropriate “ACT” option, or series of options, to get the monster to agree to spare you. For Loox, that’s “Don’t pick on”, as he requests of you through in-battle dialogue, and for sad Napstablook, that’s three “Cheer”s, followed by a fourth after he shows his hat.

Even from a broader, literal perspective, Undertale is still not a single story–it has three separate narratives that can occur: True Pacifist, Neutral, and Genocide. The sheer contrast between the Genocide and True Pacifist routes makes them feel like completely distinct games, set in the same world, which each show two completely different sides of the monsters. This is a big part of why Undertale characters are so memorable and beloved; they have so much depth, so much detail, and so many stories that they feel almost real, despite the distance of the screen.

I have always looked up to Undertale for its use of making the enemies more real and making how you treat them a mechanic. You bringing up the difference in naming is very interesting though. Enemy is ambiguous, often it has human connotations but most people know “enemies” can refer to nonhumans. Monster, however, is very commonly used to dehumanize someone. Which plays directly against Undertale’s message. But this doesn’t take away from it, in fact, the tension builds the argument even more as it continues to hammer home the idea that games have been working to condition our minds away from empathy in some capacity.

The depth of the characters and the change in focus of the battles from the player character to the monsters really sets Undertale apart from the rest of its mechanical genre. The player has to pay attention to the other combatants, one way or the other, much more intently than they would in, say, a Final Fantasy game or even Earthbound. It seems like Undertale has its own specific message, which is that the major characters in a narrative aren’t the only ones who have a story. Bit characters like the dummy, Napstablook, and the Royal Guards all have their own places in the game’s world, and their stories are allowed to play out… provided the player doesn’t, y’know, eviscerate them.

I really loved your post on Undertale. I do truly believe Undertale is one of the most beautiful games out there. I feel like it even goes beyond the enemies and how these “monsters” are actually “humane” or contain emotions, although they executed it beautifully. I feel like it even gets you to love your companions and the people in the Underworld; we’ve seen how many people love Sans, Papyrus, Undyne, Alphys, etc. but I didn’t think about it until know how much I love even these very much side characters like Monster Kid, Tem, Bratty and Catty, and so many more.