Sometimes it’s hard to play slow games. I have to admit it. Sometimes I just want the fast paced, shooty, slashy, bright and flashy action that comes with so many modern titles that I play. Even as I delve into ancient videogame history and confront the Isle of Myst, I find myself spam-clicking my way through the screens, trying to move through limited controls as fast as I possibly can. I feel like in nearly every aspect of my modern life, I am conditioned to move as quickly as possible from point of interest to point of interest – work faster, play faster, scroll faster. I can’t help but remember the words of countless boomers – “kids these days, soon they’ll have the attention span of a goldfish” – is it really true?

In comes Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn (2018). Obra Dinn asks the player to carefully and deliberately traverse a once-thought-lost shipping vessel and the lives and deaths of its crew, collecting information on their identity, cause of death, and killer to report as an insurance claim to the East India Trading Company. This premise already sounds like it will struggle to satiate my Gen Z brain’s constant need for dopamine. But maybe there will be cool action scenes and awesome dynamic controls to really punch it up! No. Obra Dinn sets the player’s walking speed at nearly a crawl and makes them sit through long transitional cutscenes, long sequences of pages turning and writing appearing on pages, and unskippable dioramas, where they are unable to progress until the music has run its course. Everything about this should have frustrated the hell out of my overactive, sensory seeking brain. And yet…

The longer I played Obra Dinn, the more comfortable I felt slowing down. Sure, I certainly started in my min-maxy ways, attempting to identify all of the information as quickly as possible and before the death pages opened to me, or find the body that would be highlighted by the shaking pocket watch before the initial search time was up (literally just so I wouldn’t have to run over and could click confirm right away), or sprint as quickly as possible to the destination of the flowing white smoke, only to be super frustrated when it took such a circuitous path to reach me. But as I continued to play, I found that I began matching the slower tempo of the game, taking time beyond that allotted to me to explore each diorama, and flowing with the smoke trails instead of frustratedly waiting for them to arrive. What caused such a change in my pace of play? How did this game so quickly transform me from a dopamine junky into a chilled out, zoned in insurance collector? (I am hyperbolizing my experience here and throughout somewhat, but only slightly).

Obra Dinn has a special knack for demanding your attention. It functions fundamentally differently from most puzzle games I’ve played in a number of ways that force you to zone in or get lost. Most puzzle games rely very heavily on visual elements – most often in motion or interactable – to communicate their information and form the substance of their puzzles. Obra Dinn challenges these tendencies by separating both of these key features – things in motion and interactable things – from the main visual space of the game. All of the motion of the game (beyond that of the player moving around) comes in the form of hyper-detailed moments of (visualless, subtitle only) dialogue – or just gore noises, in some cases – that depict the moments before the death of whichever crewmember’s body you just found. These audio-plays demand absolute attention from the player. They not only set up all of the context for the diorama of death to follow, both situating the player in the timeline and often establishing motive, but they also provide invaluable information about the identities of the characters in the diorama, be it through name, accent, affect, use of formalism or even location in stereo space. These soundbites form the body of the story of Obra Dinn, offering not only narrative context, but essential mechanical information to the player on their quest to unravel the fate of the Obra Dinn. They require careful, undivided listening and re-listening to pick apart all of their meaning and information. You can’t just hear the story of the Obra Dinn, you have to listen.

Likewise, the vast majority of interactivity in the Obra Dinn is confined to the player’s record book. Rather than gathering pieces of evidence, pointing accusatory fingers, or seeking out hidden doorways or hidden messages, Obra Dinn offers the player a static 3D diorama, a sketch of the crew, a ledger, and map, and asks them to do nothing more than fill in the blanks of their book. Even the limited intractability the player has in the 3D playspace of the game of the game funnel back to the book – focusing in on a given character shows their picture from the sketch (and opens to said sketch upon opening the book), or standing over a dead body and opening the book flips to that body’s death page. Obra Dinn asks the player to take time to sit with information, cross reference, flip back and forth, check and recheck, and just think.

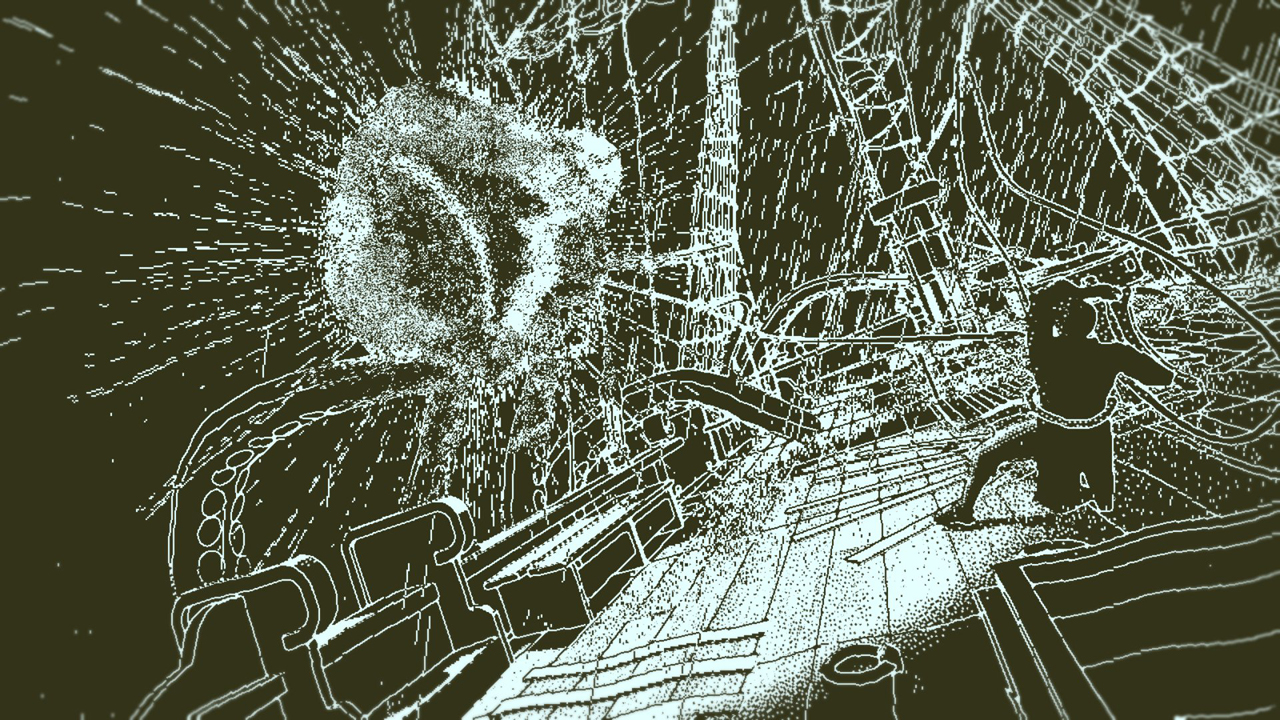

Even in the dioramas themselves promote this careful, slow attentiveness – you are forced to stay in each for at least a minute before you can even begin to enter information into the book. To complete the game, you must carefully scour every last corner of each diorama, looking carefully at the physical appearance of each character, their mannerisms, where they are, what they are doing, all just from a frozen moment in time. More than once, essential information about the identity of a character is revealed when they are in an entirely different room or side of the ship, not at all involved in the action and death that is unfolding around them. You must do more than just observe, you must look.Obra Dinn is a game that exists in an expanded moment; rather than fast paced action and new sensory input by the second, it separates the senses and makes the player live in an instant for minutes at a time. It immerses the player into this expanded moment, requiring their attention to every detail, sonic, visual, or logical, to unravel the fate of the Obra Dinn. It slows the player down, asking them to methodically sift through the chaos of the Obra Dinn and make sense of what was once nothing more than rapid, senseless violence and noise.

Excellent point. I found your thoughts on the audio aspect of the game particularly interesting with respect to attention—the contrast between the brief, expressive soundbites and the procedural, drawn-out moments of detective-ing stood out to me. I found myself leaning closer to the screen whenever a new memory was beginning, trying to hear the scene before I saw it. I think, in some sense, as a result of the audio primer, each corresponding detail I noticed in the memory afterward was like a mini “a-ha” moment, which further heightened my immersion. I wonder how different the game would be without such convincing voice acting and sound effects, or even if it was just some basic form of “voice” like in Undertale.