There will be heads ups for each game, but major spoilers for Save the Date, Metal Gear Solid 2 and Hotline Miami, as well as minor thematic spoilers for One Cut of the Dead and Breakfast of Champions will follow.

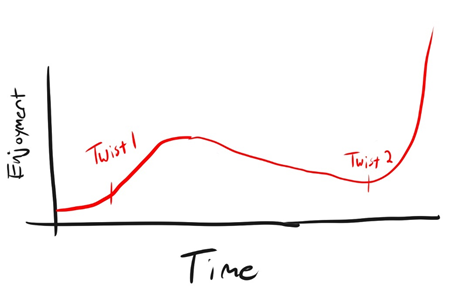

Here is a chart of my enjoyment of Save the Date.

Those who have played Save the Date may be able to infer what “Twist 1” and “Twist 2” are – namely, the first refers to the reveal that progress is actually carried over through playthroughs (with the player avatar realizing that Felicia may be doomed to die and making such a realization apparent through narration), and the second referring to the reveal of the meaning of the game (this is roughly when we arrive at the “Hogwarts pickup spot” and Felicia’s character becomes, well, more of a character).

If you know me, you may know why I liked the first twist a little and the next one a lot. Cool tricks using gaming’s meta elements are something I’m always a fan of (as trite as they have become in modern times), but commentary on a work’s own medium is my jam. Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions is one of my favorite stories, and is also a book about books. Same thing with Shin’ichirō Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead – that’s a movie about movies, and one of the most enjoyable films I’ve seen to date (if you’re interested in seeing this one, don’t look up why it is a movie about movies, just watch it for yourself!).

What I find most fascinating, however, are games about games. These include Hotline Miami, Metal Gear Solid 2, and, now, Save the Date – all of which sit among my favorite titles. I want to use this time to quickly touch on how each makes commentary about games as a media, and what makes each of them special in that regard.

Hotline Miami

When I say “Hotline Miami is about violence”, I don’t mean it in the same way that Mario is about jumping. There certainly is a lot of violence in Hotline Miami, and almost all of it is done directly by the player. Violence is, in fact, pretty much the only way you can interact with Hotline Miami’s world.

But the real reason why I say this is apparent in the game’s first scene, where they are asked “Do you enjoy hurting other people?”. At first glance, this question seems posed for the player character (a man who will go on to slaughter thousands of faceless Russian mobsters), but in actuality, it’s posed to the player – the person who will actually control the murders of said mobsters with glee. The game goes on to cut off its own iconic high-intensity electronic music every time you finish a level, forcing you to walk back through hallways of mangled corpses in silence, and ends with revealing that all your carnage was, of course, at the hands of some faceless underground organization. But when you question why they made you do it, the figures laugh – did you really need a reason why?

There is certainly something to be said about games that attempt to make commentaries on game violence while also featuring violence as a core mechanic, in the same way that some question whether one can make war movies about war. To make a war movie, some critics argue, is to glorify it in some capacity, no matter how many horrors or deeper meanings are shown, and I would guess that such critics would point the same fingers towards Hotline Miami’s pulse-pounding action. Still, I feel like this game makes careful moves to never glorify its own atrocities, and such moves can often make unique use of games as a medium (such as the title’s restrained use of dialogue choices, multiple player characters, and backtracking). In turn, I would highly recommend Hotline Miami to anyone who can stomach it.

Metal Gear Solid 2

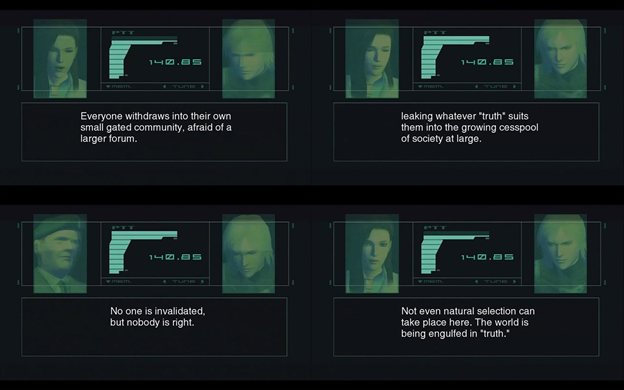

If you know me, you know I can’t shut up about this game. And, apologies to my friends who will hear me talk about it yet again, but – how could I not? Widely considered to be the first post-modern game, Metal Gear Solid 2 is one of the most profound pieces of media I have experienced, like, ever. It also predicted the rise of fake news, internet censorship, destruction of the Twin Towers, social media-bound conspiracy theories, and a lot more.

But how is Metal Gear Solid 2 a game about games? To do that, we need to look at the context of the title’s development. It came right off the heels of the PlayStation’s Metal Gear Solid, which was a booming success and a major founder in the use of cinematic storytelling in games. Further, the story and themes of the first game, as fascinating as they were, were pretty standard as far as espionage thrillers go (albeit from some interesting commentary on genes).

Here is where the sequel comes in. Instead of continuing with a formula from the first game (which would be known to make tons of money), Kojima Productions went in a different direction. They began by seemingly killing off the beloved protagonist of the first game after two hours of play. Then, they made the players play as a more feminine and reserved Raiden for the title’s remainder. Finally, they capped off the game with a long speech about internet censorship, a katana fight with the U.S. president on top of Federal Hall, and a scene where Raiden throws away dog tags with the player’s own name on it. Also, the big baddies (the elusive Patriots and their world-controlling AI) win.

The wider public hated this upon release, and who can blame them? Metal Gear Solid 2 went against expectations in nearly every way. What many didn’t realize, however, is that it subverted these expectations for good reason. They wanted players to notice these subversions, and come up for their own interpretations for why they were made. Through this, Raiden becomes a medium for the player in more ways than one – he, just like us, idolizes Solid Snake, and has gone through simulations of the first game’s events (just like how we literally played them!). The moment when he throws away our name, then, is imbued with profound meaning, inspiring questions on what it means to act as a conduit for a player and the limits of our own agency. This is just one aspect of what makes this title a game about games, but going further would require an unfeasible page count.

Save the Date

I may be fudging my definitions somewhat, as I believe Save the Date is more about stories than it is games. One might say it would be better to call it a story about stories. However, there are countless ways that make Save the Date a story that must be told in the medium of games (most importantly, the use of multiple profiles and constant use of game vernacular within its text), so I feel comfortable including it among these titles.

This is a game about saving your girlfriend, Felicia. Whenever you take her out on a date, she seems to die, let that be from an allergic reaction to peanuts to falling off a collapsed balcony to getting caught up in a ninja attack. Through your knowledge of earlier playthroughs, you can explore different options in hope of preventing her death, and the game is aware of this, making new dialogue appear after you explore these playthroughs. If this was all the game was, however, it would be a cool but ultimately forgettable title.

No, Save the Date is special, and it is special precisely because it is, also, a game about games. Near the title’s conclusion, you use your hard-earned knowledge to take Felicia to a secret location that overlooks the city where the game’s events take place in. However, even here, she seems to always die – falling victim to falling statues, meteor strikes, and alien attacks alike. At the same time, however, this is the first time Felicia can be made fully aware of not only her own constant loop of death, but also as her status as a video game character. And what does she have to say after making these realizations?

Well, she tells us to stop playing the game.

Thinking about it, of course she would want us to stop playing – to her, every new playthrough is a new gruesome demise. But it goes further than that – in doing this, Felicia criticizes the player’s inherent want for some secret, good ending, where he can save her. In actuality, there aren’t many options for her to live within the game, you can hack the title to unlock a hackney “good” ending, or avoid going on a date, which will prevent her death at the cost of your relationship with her. There is a third way, however, for her to survive, but not in a way that most gamers would expect.

This would be in the route where Felicia instructs the player to exit the title and make up their own ending, as if they don’t, she will surely die. In my playthrough, I played this route to the end just to make sure that she is right (she is), and then played another one to the same place, exited the game, and never opened it again.

This is what I consider to be the game’s canon ending, and is what makes it a profound statement on storytelling as a whole.

Why do we seek clean, good endings, at the cost of all else? What is wrong with making up our own divergences from stories? Does the media we interact with exist separate from us, or is it only in our head?

Save the Date doesn’t have the answers to these questions, but it will certainly help you come up with some. And I think that is pretty cool.

Works Cited

Hotline Miami. Directed by Dennis Wedin, and Jonatan Söderström, 2012.

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of the Patriots. Directed by Hideo Kojima, 2001.

Save the Date. Directed by Chris Cornell, 2013.