What does it mean to be ‘in the zone’?

Think back to the last time you were deeply enthralled by an activity. Remember how it felt to reach that strange zen where reality itself fades away; so immersed that before you know it the sun had set. That flow state better known colloquially as ‘being in the zone’ is a mental state in which one becomes fully engrossed by their present situation. Three key distinctions of flow are the distortion of temporal experience, intense degree of satisfaction and concentration, along with a momentary loss of self-reflection. Games routinely attempt to use this to their advantage for player engagement. Flow however, is not a binary state, it’s a gradient.

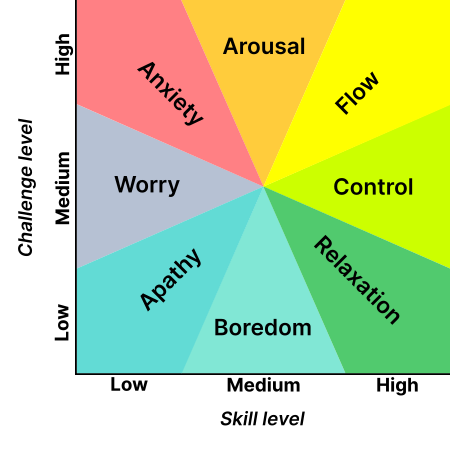

This zone is highly dependent on one’s skill and the challenge imposed by the activity. Thus developer have the delicate task of imposing obstacles that fit the demographic of their genre. Consider that a game like Stardew Valley (a farming sim) will often aim to keep a player relaxed, but still present forms of progression so as to not lead players towards boredom. On the other end of the spectrum, Outlast (a horror game) must create obstacles that feel insurmountable without creating frustration or off-putting levels of anxiety. It is also important to consider that flow is highly reactive as a person ability begins to match the challenge. This means developers must find methods to dynamically scale difficulty in a manner that generates momentum or maintains flow.

Tetris is Timeless

Tetris is perhaps the most notable example of flow usage as evident by its continued success. How is it that despite decades of re-releases with almost no innovation it is still enjoyed by countless of people?

It likely has to do with its direct appeal to human aesthetic need for visual/geometric order. The gameplay loop is easy to understand, but still provides very visceral feedback. It is this openness in interpretation that Tetris can mean different things to different players. This is especially important when in regards to difficulty. The game is relaxing when taken at a pace below the player’s skill while still challenging when seeking high scores. There is little punishment for a mild performance, instead the game incentivizes skilled play by displaying additional fanfare when going for strategic chain combos; in turn the game reacts to their ability (by proxy of score) by raising the speed. Although losing is inevitable, the player is still fulfilled by the experience because of the gratification involved from being in the zone and stringing successes.

Achieving flow in Rougelikes

Difficulty is a staple of rougelikes. This is often due partly to the randomness requiring quick improvisation, but also the relatively complex mechanical input required. In order to offset the possible frustration associated with adjusting to this playstyle most modern rougelikes offer safe havens.

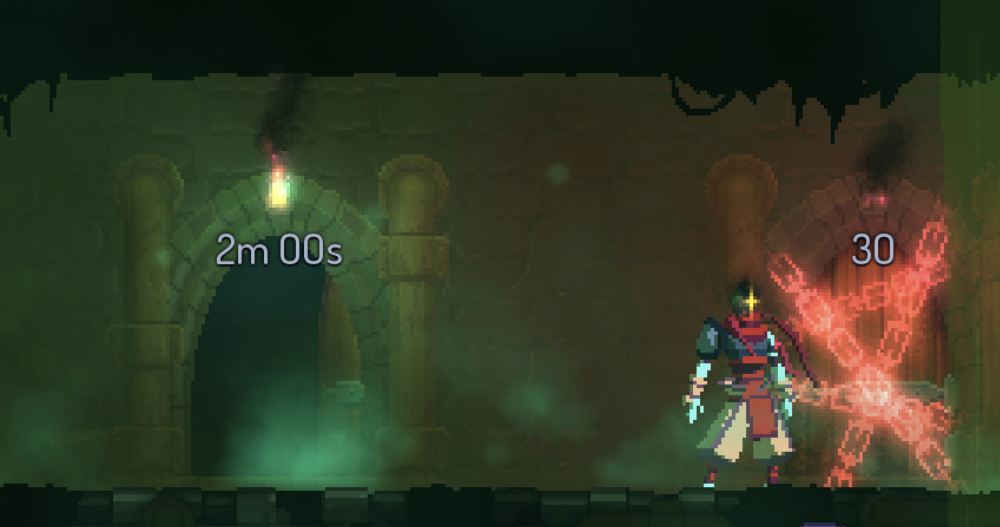

The player is able to take the time to strategize and prepare for the road ahead at their own pace. However, in comparison to Tetris these games present greater opportunities for risk-taking for players of high skill level. For example, in Dead Cells a skilled player might be willing to gamble their entire run on a cursed chest or timed doors for much rarer rewards they would have gotten otherwise.

Cursed Chest begging to be opened.

Who knows what sort of treasure hide behind these doors?

In the case of failure they are able to reconsider their choices on the next run and play more reservedly. If successful the player is able to then leverage their new found strength into further gambles creating momentum. This idea of momentum is extensive, even on a micro scale, as the player is rewarded with a speed buff for kill combos enabling even faster and easier kill chaining. Arguably, momentum is less about the character’s raw strength and more about creating a state of hyperfocus. When a player becomes deeply aware of the state of the game and are comfortable with their ability they are more likely to succeed or recover even when situations become unfavorable.

Reaping the benefits

Once in the zone a player can potentially rampage through lower level content providing a steady stream of satisfaction. It’s important to consider that this ‘god-mode’ is transient, with games quickly becoming boring if they posed no challenge. This is where new game plus enters the fray, allowing for these players to immediately engage in more challenging content. Eventually the game will reach a point to where it can either no longer provide the necessary challenge on its own, or the player has hit their skill ceiling. But that is okay. No single activity can, nor should, aim to provide the complete mental engagement of a person forever. Instead we can come to appreciate the fleeting occasions as they happen and learn to let them go.

Related Posts:

Death & Progress in Video Games

What Roguelikes/Roguelites Teach Us About Failure

Randomness:the most cost-efficient key to increase the playability

One genre that I think is built on the concept of player flow state is rhythm games. Most rhythm games have a combo system that rewards players for not missing a single note, which is a difficult feat. However, many players (including myself) talk about entering “the zone” while playing, where their hands move on their own and they’re feeling the beat of the music. It’s kinda similar to how I felt after getting a speed bonus in dead cells. The game similarly rewards “full combos” in the form of defeating a certain amount of enemies without getting hit. Rhythm games and Dead Cells are both fast paced, and i do think that this high speed is important for creating a flow state. While I’ve had insane decks and power trips in Slay the Spire, I’ve never been “in tune with the game itself.” Maybe there is a way to make a flow state for slower games, but I think it’s much easier to design around in faster games.

This was such an interesting psychoanalytic take on how video games can be made to maximize a player’s playtime by hitting the sweet spot of challenging, engaging, and relaxing. Even to a new player of video games like myself, a game like Dead Cells put me ‘in the zone’ as the aspect and the challenged of the repeated deaths made me want to play over and over again in order to build upon the knowledge I had previously. Your post also reminded me of how Flappy Bird was such a significant phenomenon at one point in our lives, and thinking about how it was challenging in the way that there was no end/no ability to really win against other people/hard to get the bird not to touch the pipes, but also easy to play in the way that the controls were super easy to maneuver and it was a phone game that was easily accessible to all. There is definitely a way to get into ‘the flow’ while playing Flappy Bird, and there was something really addicting about trying to reach the state where getting the bird past the pipes was easy. Great article!!