Super Momotarō Dentetsu (Momotarō Electric Railway) was released in 1992 for the Famicom as the second installment of the Momotarō Dentetsu series. The premise of the game is that players are traveling around Japan by rail or by ship, buying up properties and thwarting their rival entrepreneurs. The gameplay itself is designed to draw upon the mechanics of a board game.

The game is meant to be multiplayer and there is a turn rotation system. Each turn, a player may choose to play a card, or roll a dice to determine the number of spaces they can progress forward. Players can choose how many years they want to play for, and each cycle of player turns represents one month. The short term objective of the game is to be the first player to reach a particular major train station. Once all the years have been completed, the player with the most amount of money wins.

For context, the tale of Momotarō is about an elderly couple who find a giant peach floating down the river one day. From the peach is born a baby boy, Momotarō. When Momotarō begins to grow up, he sets off on a journey to defeat the yōkai on Demon Island. After vanquishing the demons, he returns home.

Originally, I wanted to play Super Momotarō Dentetsu because I had done previous research on how this folktale character, Momotarō, was mobilized during World War II as a symbol of Japanese imperialism in the animated war film: Momotarō: Umi no Shinpei. When I first looked into the game and saw that players were competing with each other as railway tycoons, I became curious about whether this figure was being appropriated for a new narrative about Japanese industrialism or capitalism. However, my experience playing this game caught me completely off guard. Despite being so eager to connect this game to my larger body of research, as I began playing, the insights the these critical lenses could offer me seemed to pale in comparison to my profound feeling that Super Momotarō Dentetsu was wholeheartedly trying to make video games, as a medium, an accessible and democratic space for people in Japan.

When I was searching for a way to play this game, I was unable to find any emulator with English translations. In the end, I played the game using a translation guide by E. Phelps. In Phelp’s introduction to the game, they provide insight into why this game about trains is connected to the folktale of Momotarō at all, “Momotarou Densetsu (“The Legend of Momotarou”) is an old Japanese folk tale, familiar to all Japanese people just like English people are all familiar with Jack and the Beanstalk. This game’s title, Momotarou Dentetsu, sounds a lot like the name above, but is translated (“Momotarou Electric Railway”).” Embedded in the iconography of the game is a folktale figure that is “familiar to all Japanese people.” The imagery in the game that draws on Momotarō, as both a folktale figure and as a young Japanese boy, makes this game accessible to all age groups and provides a democratizing cultural reference point for new players to latch onto.

The mechanics of the game are very analogous to that of a board game which makes the game more accessible to individuals who are unfamiliar with video games. The A button is used to roll a dice, which bounces across the screen in a way which flattens the entire game space to resemble a tabletop experience. The special actions of the game come in the form of “cards” and the effects of each “card”is on a menu during each player’s turn. Through the turn system and card and dice mechanics, Super Momotarō Dentetsu makes its gameplay accessible to a large audience. Furthermore, when players choose which direction they want to move their train in, the game does not punish players for accidentally moving in the wrong direction. If the player moves back a space, prior to using up all of their available moves, the game simply restores that “move point” back to the player. This, in combination with the dice roll and menu being activated by pressing one button, relieves the burden upon the player to be dexterous or familiar with video game controllers.

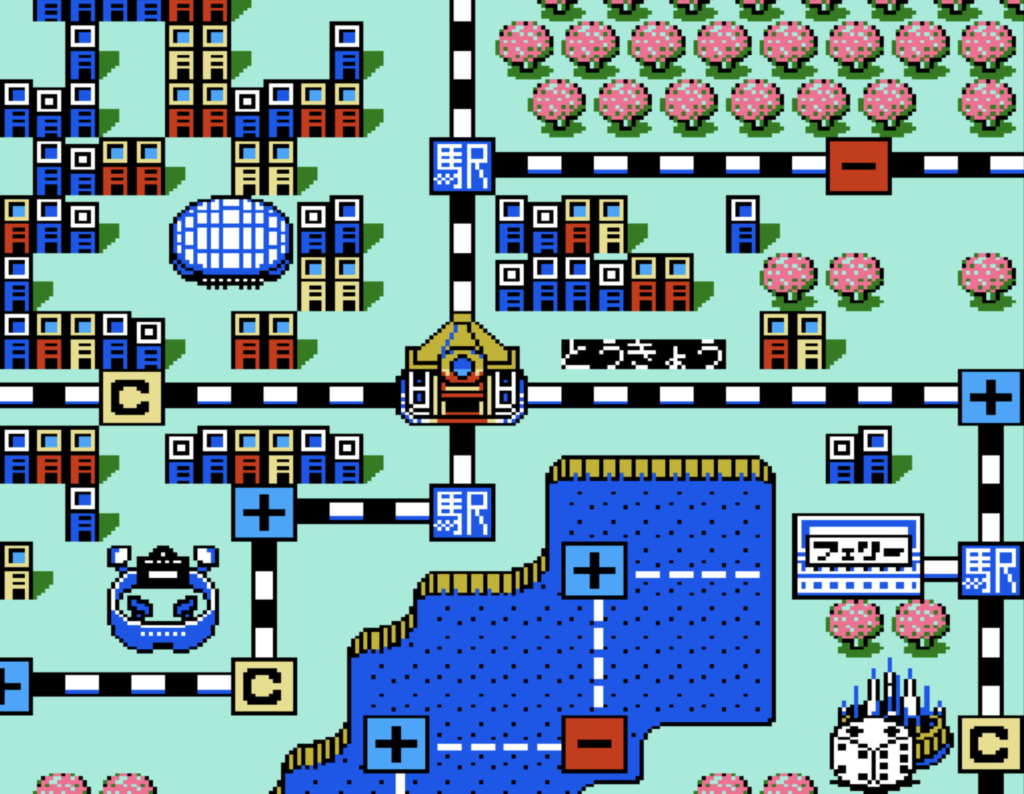

While many of the challenges in this game are based around the luck of dice rolls and card picks, what I found the most difficult about this game was probably intended to be another democratizing feature. The board of the game is essentially a geographically accurate map of Japan, and the player’s job is to navigate the railway system to reach a particular station first.

The game assumes that the player knows their Japanese geography and does not provide clear hints about what direction to go in. Part of the excitement of the game is that the spaces beyond the field of view are hidden, so players will not know what they might land on if they go in a particular direction. For this reason, the player cannot look around the map to orient themselves. In my experience playing against two computers, I constantly was typing station names into Google Maps, trying to figure out what direction I needed to head in. However, when considering who the game’s intended audience is, the choice to make the map based on Japan places value on the player’s knowledge outside of a video game setting. The reflexive understanding of where these places are located for a Japanese player adds another familiar reading practice onto the game, it is basically navigating a real world map. Additionally, this is presented to be analogous to the map of the public transportation system in Japan.

While there is certainly an argument to be made about whether this game is an actually advertisement for the Japanese train system, or about how this game’s real world mapping of Japan extends Momotarō as a figure of imperialism, I could not bring myself to focus on these aspects while playing. Instead, my experience with this game resonated deeply with a movement towards making video games, as a medium, more accessible during the era of this game’s release. I think Super Momotarō Dentetsu’s iconography and mechanics were meaningfully aimed towards a broader audience and as a multiplayer game, it presents itself to be played in a social setting and to be shared with others. While this game’s content is quite inaccessible to non-Japanese speakers, as well as to people who may not be familiar with Japanese geography, the game’s specificity towards its intended audience allows it to draw upon cultural reading practices that best suit its players.

This game franchise’s success continues to flourish in Japan today. According to Nintendo Life, as of May 2021, the series’ new release for the Nintendo Switch has surpassed 3 million sales copies, despite remaining a Japan exclusive game. It appears that even as video games rise in popularity and gaming literacy is higher than ever, Momotarō Dentetsu’s mobilization of accessible cultural icons and spaces continues to make it a tenderly cultivated experience for players in Japan.

Works Cited:

Craddock, Ryan. “Momotaro Dentetsu Surpasses Three Million Sales on Switch, Yet It’s Still Exclusive to Japan.” Nintendo Life, Nintendo Life, 13 May 2021, https://www.nintendolife.com/news/2021/05/momotaro_dentetsu_surpasses_three_million_sales_on_switch_yet_its_still_exclusive_to_japan.

LastBossKiller. “Super Momotarou Dentetsu Strategy Guide.” GameFAQs, 10 Aug. 2014, https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/nes/580602-super-momotarou-dentetsu/faqs/69756.

“Momotaro Dentetsu: Showa, Heisei, Reiwa Mo Teiban!” Nintendo Everything , https://nintendoeverything.com/momotaro-dentetsu-showa-heisei-reiwa-mo-teiban-gets-new-trailer/.

What a cool game to review! I’ve heard of the series but never acquired the hardware to play, so reading your review was super interesting. The fact that it hasn’t been ported to English speaking audience does speak volumes on how culturally rooted it is in Japan. While it would be awesome to be able to play it in English, it really seems like so much of the nuance in dialogue and gameplay would be entirely lost, if not just straight up impossible to achieve, in localization. Even the game’s name, being a play on words, would be impossible to properly capture in any other language. It’s very nice to see such an underappreciated game in the West being discussed!