I first encountered Galaga as part of a Ms. Pac-Man combination arcade cabinet at a pizza restaurant in Austin, Texas. I fondly recall asking my parents for quarters to dedicate to these two games, which I remember as the only two video games they ever didn’t begrudge my playing. This was likely because, unlike my other favorites (Pokémon SoulSilver and Wii Sports: Resort), these were games present for them at the exact same stage in their lives. Neither of my parents, who were each born in 1972, ever owned an NES or Atari, so console gaming struck them as foreign.

But there was something more universally social to them about an arcade cabinet. As non-gamers, this proto-multiplayer environment (and early multiplayer, in certain arcade formats) was the only obvious social enterprise video games could provide access to. Public records of high scores and dueling joysticks invite players to treat the games socially and competitively by their very nature, and this, at least, was something my parents felt deeply enough to support in my younger brothers and I.

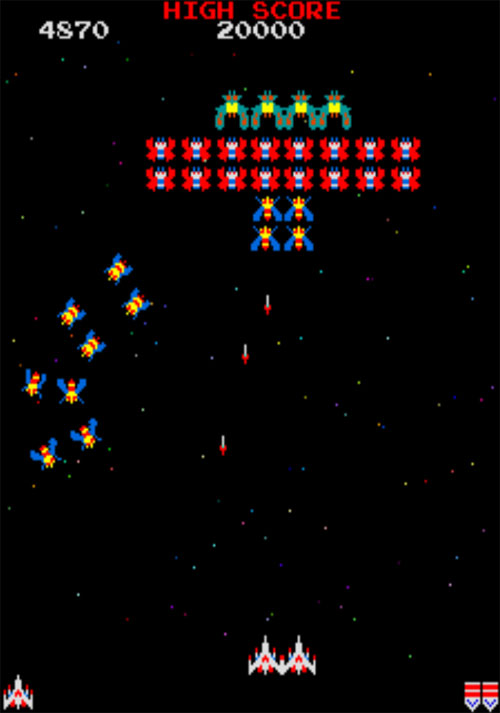

And there was a more specific place my parents, brothers, and I could find common ground in gaming: Galaga. This world-famous 1981 arcade blaster game borrows its mechanics heavily from Space Invaders and its predecessor, Galaxian, with one small inventive twist particularly setting it apart: the ability to “recapture” a ship. Rather than simply blowing up the player’s ship with laser fire or physically crashing, certain enemy ships could project a tractor beam that would suck up a player’s ship and return them to the top of the screen, making the player lose a “life”. However, if on the next life the player could destroy the tractor beam ship without destroying their lost ship, the captured ship would join the player’s ship for double the firepower.

So this is a clever mechanic, but what makes it so special? I would contend that Galaga is a powerful and universal game by seizing on two fundamental game elements that had existed long before its creation: the satisfaction of cleaning, and the magic of a secret menu.

Game genres are often defined in terms of familiar blends of mechanic and aesthetic- roguelikes, first-person shooters, and comfy games each carry fundamental mechanical ideas in concert with, or complication of certain typical aesthetic ideas. But to zoom out further than even genre, a broad swath of games (video and otherwise) refer to the appeal of clearing a space. The aim of a first-person shooter might be to slay every zombie in the environment, or the aim of a restaurant management game might be to satisfy every customer before close. Looking beyond aesthetic and narrative motivations a player might have to clear these spaces, however, why is this format chosen to best gamify and simulate these environments? The space-clearing appeal seems to be a fundamental concept that exists beyond external signifiers as a (psuedo-)universal mechanic satisfaction, especially for single-player endeavors, wherein a developer cannot rely on social pressures to incentivize thorough play. Take the prior appeals-to-clearing of Solitaire or Mancala- gamifying clearing has long been recognized as being among the building blocks of many play experiences.

Galaga takes advantage of the space-clearing appeal by appropriating both the fundamental clearing mechanic and space-age aesthetic of the Space Invaders model, but the ship-recapture mechanism serves as a fulcrum point for both using this appeal to its fullest potential as a single-player matter and introducing a mechanic that generates social appeal. Beyond the obvious social signifier of the high-score mechanic, which even at this point was well-worn across the arcade gaming milieu, the dual ships mechanic is not made explicit in the game’s play (although certain cabinet decals do allude to its existence). By including a hidden mechanic like this in an accessed-in-public but single-player game, even if the mechanic is only mildly shrouded, Galaga is able to do exactly what In-N-Out burger has seized upon anytime a customer orders a burger animal-style- a non-advertised, surprising mechanic serves to make the game a conversation piece in itself. Future, more complex games with large worlds to explore like Skyrim and the Pokémon series have built entire communities around communicating and unlocking their secrets, but Galaga was one of the first to seize upon the intrigue of rudimentary playground gaming myth. The dual ships mechanic even serves to emphasize the aforementioned clearing appeal, as it provides one more obtrusive element that this time one must tread lightly around. I certainly remember my father showing me the recapture trick the first time I ever played Galaga at my local pizza restaurant, and to this day it is the single instance I can remember of ever connecting to my parents through video gaming, a medium they (and even I sometimes) generally resist.

Galaga elaborates upon the broad appeals of many arcade game modes by providing a distillation of the space-clearing appeal and an early case of video game mythmaking, serving as both the apotheosis of one form of gaming appeal and the early genesis of another.