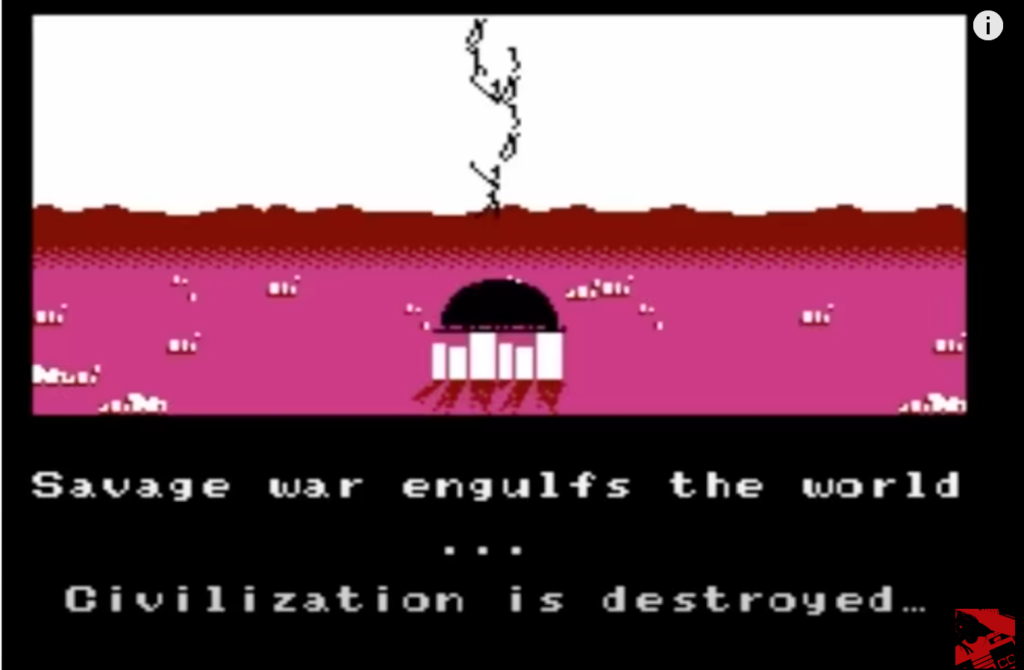

“October 1,1997. The end day. Savage war engulfs the world. Civilization is destroyed. An evolution had taken place. The earth’s axis shifted and all creatures became mutated. Life would never be the same. Those surviving vowed not to repeat their mistakes of the past and erected a great tower in the sky to oppress evil forever…”

This is the introduction to Crystalis, a Japanese role-playing action-adventure game released for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1990. The game takes place in a post-apocalyptic future that has been ravaged by nuclear war. The war ended modern civilization: the few survivors gave up science and technology after seeing its consequences and instead decided to only use magic. They have also built a giant floating tower, where they plan to live away from the dangerous mutants who roam the earth and keep guard against any future wars. The game follows a male protagonist–a scientist who awakens in the year 2097 after being cryogenically frozen for 100 years. He soon learns that a villain known as Draygon is attempting to combine science and magic to infiltrate the tower and conquer the world, and it is the protagonist’s destiny to stop him.

The game’s mechanics and visuals are fairly standard, and are reminiscent of earlier fantasy and adventure RPGS such as Legend of Zelda. Just like Zelda, the world of Crystalis is seen from a top-down viewpoint and the protagonist can move both vertically and horizontally. In addition to these movements, the protagonist can attack enemies with one button and use items or magic with another button. The protagonist also has an inventory where the player can store and access weapons, tools, and a variety of items including armor and medicinal herbs. However, underneath the simple 8-bit graphics and the somewhat customary mechanics lies a deceptively dark tale that carries with it the mass trauma of an entire nation.

In 1945, two atomic bombs were dropped in Japan, resulting in extreme consequences that were still being felt and reckoned with when Crystalis was released 45 years later. The critical role that this tragedy plays in the game’s narrative is evident from its start, which describes an apocalypse caused by nuclear bombings while the graphics show a mushroom-shaped cloud enveloping an urban skyline. However, Crystalis goes much further, incorporating the effects and consequences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki into even the smallest details of gameplay and character interaction. One of the most evident ways the game accomplishes this is through the enemy structure. At the beginning of the game, the player mostly only interacts with enemies in the form of mutated animal-like creatures that roam the earth. However, as the game progresses, the player encounters higher level bosses, all of whom are humans who work for Draygon. After Draygon is defeated, the ultimate boss is revealed: DYNA, the powerful computer that runs the floating tower. Another relevant aspect of gameplay is that while the majority of the mutated creatures do not approach the protagonist, all of the human enemies do. This hierarchy of enemies may reveal one of the ways that Japanese citizens concieved of the evils they witnessed through the bombings. Applied to real life, this framework suggests that at least a portion of Japan viewed the technology of nuclear warfare as the ultimate evil, even worse than the individuals who chose to use the technology. This argument is also built into the game’s narrative. The survivors of the apocalypse are described to be at peace because they have given up technology, and Draygon is characterized as evil in his attempts to reclaim the powers of technology. Though Japan in 1990 was certainly far from totally rejecting modern technology, millions of survivors of the bombings fought for the prohibition of all nuclear weapons, and continue to do so today.

Crystalis’s gameplay also touches on other traumatic aspects of the bombings, such as the environmental consequences. Bodies of water tend to be easily contaminated by radioactive particles, making marine life particularly susceptible to genetic mutation and other side-effects.This fact is made central in one mini-quest that must be completed in order to advance. The quest begins when the protagonist interacts with a mutated fish-like creature in a lake, who complains of being in pain. The quest is completed when the player gifts the creature with a medicinal herb.

Other mini-quests deal with Japan’s attempts to repair its national identity, as well as literally repair the ruins left by the bombings. The protagonist has the opportunity to collect multiple statues that have been lost or kept hidden by NPCs. One of the statues that the player collects is broken, and must be repaired before the game proceeds. The mechanic of collecting and repairing statues utilizes the standard RPG trope of collecting tokens or figurines while imbuing it with affective power that characterizes the difficulties of attempting to recover as a nation from a tragedy of such immense proportions.

As Crystalis progresses, it also grows darker, and the narrative does not hold back in expressing some of the more disturbing consequences of not just the bombings, but World War II as a whole. At one point, the protagonist enters a town that is largely empty. By interacting with the remaining citizens, the player learns that the town is empty because its residents have been imprisoned by the Draygonian regime and forced to do labor. One of the few remaining citizens is an old man who has been left outside to die after being unable to work further. He dies shortly after telling the protagonist what happened to him. In addition to being a clear representation of the atrocities that Japanese-Americans faced in internment camps, this scene also references the speculative fears that plagued survivors and witnesses of both the bombings and the internment camps. It is no coincidence that the town is located in a frosty, arctic wasteland that resembles the nuclear winter hypothesized by many to be one of the greatest risks of nuclear war.

Despite Crystalis’s extremely dark storyline and frank depiction of death, internment, and dictatorship, the game ends with an idealist message of hope and resilience. The protagonist succeeds in defeating both Draygon and the supercomputer, saving the world from the dangers of authoritarianism and modern technology. The game ends with the following quotation: “This will be a legend forever remembered to maintain peace and humanity…and peace will remain.” This almost unexpectedly positive conclusion is not especially surprising considering the game was released directly after the conclusion of the Cold War. Though Crystalis tells the story of a Japan still struggling with and deeply affected by the trauma incurred by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it also tells the story of a Japan that has rebuilt itself, and that has witnessed the end of the risk of imminent global nuclear war. Ultimately, Crystalis is a surprisingly moving RPG, and though its mechanics may feel familiar, it expands upon these traditional structures with the help of a complex narrative to craft a poignant and supremely underrated gaming experience.

Bibliography:

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings.” ICAN. ICAN, accessed October 26, 2021. https://www.icanw.org/hiroshima_and_nagasaki_bombings.

Listwa, Dan. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Long Term Health Effects.” Center for Nuclear Studies. Columbia University, August 9, 2012. https://k1project.columbia.edu/news/hiroshima-and-nagasaki.

NintendoComplete. “Crystalis (NES) Playthrough – NintendoComplete.” Youtube Video, 3:42:21. July 6, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTfTvrVvkZ8.

SNK. Crystalis. SNK. Nintendo Entertainment System. 1990.