Before this class, I never knew anything about metagames, and I never successfully finished reading any metafiction. However, after learning about the real meaning of the metagame and its underlying mechanism, I gradually learned to appreciate it.

In this blog post, I want to differentiate between games that utilize “meta” elements and real metagames. Then I want to make an analogy between metagames with cubism in art history to demonstrate the value of metagames and how it should be appreciated.

For most of us, playing games and reading novels are just different ways of entertainment. When we choose to treat games and fiction in this light-hearted way, it is not unreasonable that we will sometimes find metagames and metafiction boring.

There are essentially two types of games that involve the concept of “meta”:

The first type is games with meta elements. Instead of being their major genre, metagame is just some elements of breaking the fourth wall into which these games incorporate. In other words, this type of games retain the common game mechanics and only incorporate meta elements inside the game. That’s why this type of games usually have a wider range of audience. Metagame is the bonus scene in these games.

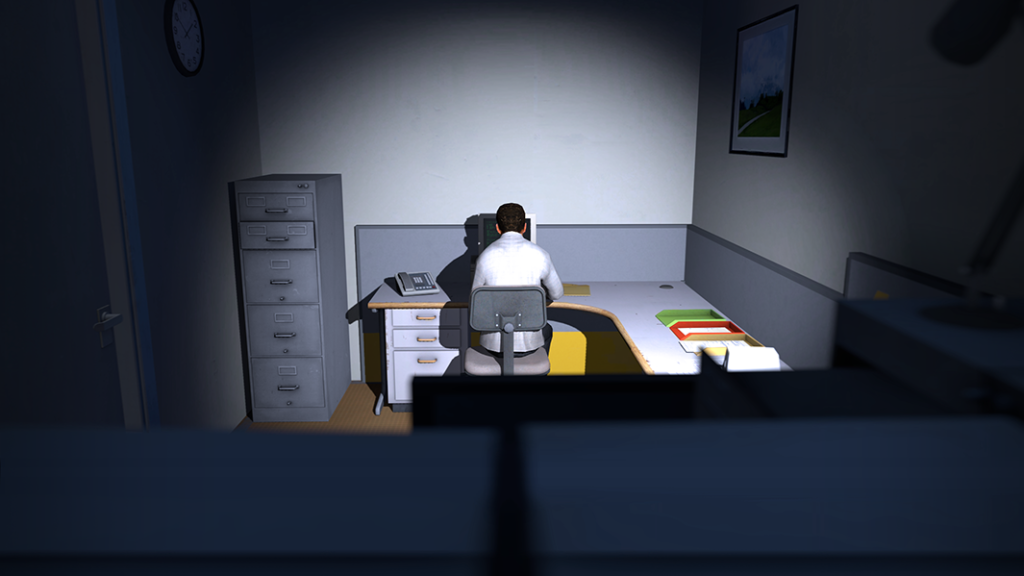

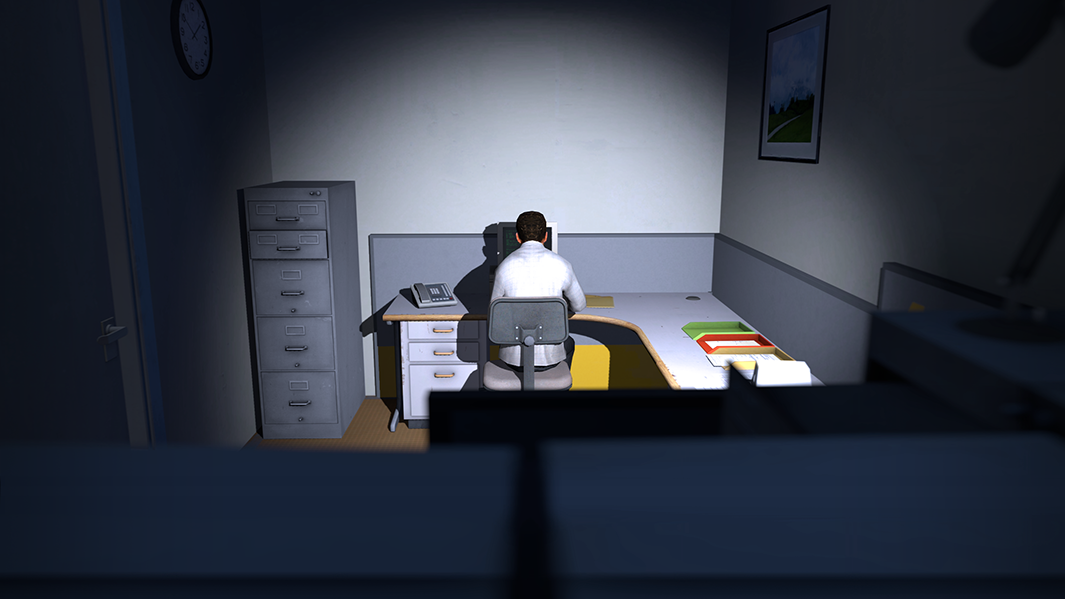

In contrast with pseudo-metagames, the real metagames’ whole purpose is to let players realize the existence of a fourth wall and try to break the boundary between reality and virtual. The metagame in this sense, represented by “Stanley’s Parable”, usually let ordinary players feel bored because they have forfeit the usual form of game mechanics.

I was among those players who feel extremely bored by metagames. However, my learning experience of cubism made me understand the value of metagame: when I first saw some of Picasso’s works, I totally couldn’t understand how these pieces of scribbles could possibly be treated as masterpieces. To me, they were not even qualified as art. However, after learning art history, I learned the development of cubism and modernism. After that, I gradually learned to appreciate Picasso’s work. It makes me understand that we have to view things in a developing perspective: the context does matter in many cases.

Just like cubism which seems to diverge from the original purpose of painting– to look real– metagames also diverge from what a game should be like. However, the reflections and revelation they give us is valuable and should be appreciated.

I really like the premise of this post. I actually find myself agreeing with a lot of your feelings to start- I also thought metagames were boring, and I think I still might not understand elements of modern art… but the idea of intentional boredom interrogating our assumptions of games is interesting- much alike how cubists intentionally subvert “rules” of art meant to promote realism. Ultimately I think this is a question we’ll tackle throughout the class, but it’s also something that got brought up at the beginning: do games have to be fun? I think we tend to assume they are intended to be fun, and drop games that we think aren’t fun, and you’re right that metagames sort of go against the grain in trying not to be fun.

Yet, I’m not sure if I wholly agree that metagames are not fun. Games like DDLC are clearly trying to be fun in some way- the poetry mechanic is intentionally boring, but the experience of the story unfolding is clearly intended to be as thrilling as something like Until Dawn. There Is No Game gives the player puzzles to solve, which are as satisfying as in an Ace Attorney or Portal game. I think that even if I wouldn’t describe the games as mindlessly fun as say, a Mario game, they still had moments of fun and intrigue, where the player is meant to be enjoying themselves.

I find myself curious while evaluating these experiences. Do these mean something? Are these the “game” element of the metagame? Is there a deeper reason players like you or I might find these experiences boring? Thank you for this analysis- I really liked reading about your personal experience with the genre!

I agree with a lot of what you said. I think it’s important to distinguish between appreciating something versus enjoying it or finding it fulfilling. A lot of the narrative driven games we’ve played this quarter for me have not been the most interesting. This however, helps us consider what we find valuable in a game—which for myself is engagement and difficulty. Even without historical context I feel that there is something to always take away from any experience even if its frustration or boredom. Our existence becomes better defined by expanding the range of our experiences and what might not click for one person might click for the next. Even if it’s not pleasant we can appreciate that there are options for people of all interests and walks of life. So really there’s at the very least two ways one can come to appreciate these experiences, one with context and one without.