Metagames are games that think, talk, mock, and open discussion about themselves as games within the social and historical context of games. This allows them to comment on problematic or inflexible genre tropes (such as in “Doki Doki”), poke fun at and invert game common mechanics (“There is No Game”), and critique the thought process behind gaming itself (“Save the Date”).

That being said, all of these games rely on some form of previous knowledge of games from general knowledge of play to highly specific genre and sub-genre community knowledge, which can make them either difficult or inaccessible from new gamers to veteran gamers of other genres (Dating Sim vs FPS vs Mundane Games). This can result in a limited audience for the game or act as a sort of gatekeeping mechanic that limits the experience for non-veteran gamers.

This is very apparent in the case of the first section of “Doki Doki Literature Club”. Each of the four girls in “Doki Doki” represent an archetype within Anime Dating Sims (the smart/quiet girl, the cute/kawaii girl, the childhood bestfriend, the class president/out of your league girl) and they, mostly, behave as such. So much so that the first part of “Doki Doki” can seem not only trivial, but cringey and uninspired to players unfamiliar to, or who do not like, Anime Dating Simulations.

If “Doki Doki” as a meta game seeks to use these tropes to their advantage (for shock and horror), or seeks to make a more social message about the toxicity of anime dating simulations and the effect their expectations have on women, its audience must know these tropes! Otherwise it is just a very scarring dating simulator instead of a game ABOUT scarring dating simulators.

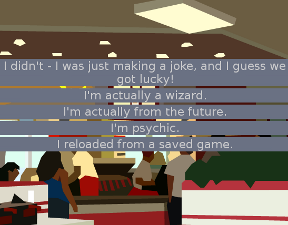

On the other hand, “Save the Date” uses common mechanics found within the game such as “save”, “reload”, repeated death/respawn, and the idea of a win state to define its ‘meatiness’. By using these easy to access mechanics and concepts that exist outside of video games such as ‘win states’ and ‘good endings vs bad endings’, save the date makes a mostly self-contained meta game that can reference within and outside of itself while still being accessible to new gamers.

Based on these two examples, the game’s audience seems to decide if it is a metagame, and that level of ‘meatiness’ is different for each player. Conversely, the accessibility of a meta game defines its audience and reach.

As we discussed in Section 3 last week, it is helpful to view accessibility in meta games as a spectrum, with games like “Save the Date” on one end and this like “Doki Doki” at the other. While Save the Date widens it’s audience to be more accessible, “Doki Doki” taps into a specific sub-culture of games and can critique it with more specificity and accuracy.

How the relationship between the accessibility of metagames and its audience is weighed is crucial to both designing and playing a good meta game. The question of how accessible can become too generalized and how specificity can become limiting is crucial to defining the next era of meta games.

I loved reading your post and I think that the accessibility of metagames is a very important topic. When I consider the target audience for each game, I do feel like it makes sense for Save the Date to have a wider accessibility and DDLC to be less inclusive for new players/players of other genres. I think the “moral of the story” of DDLC is more specifically targeted to men with unrealistic fantasies, who in general are those who would normally enjoy Dating sims. Meanwhile, Save the Date’s moral is about redefining what winning is and about not being obsessed with getting a certain ending (maybe), which could be something of relevance to anyone. I love the meaningfulness of metagames and hope that there will be more metagames from both ends of the spectrum.