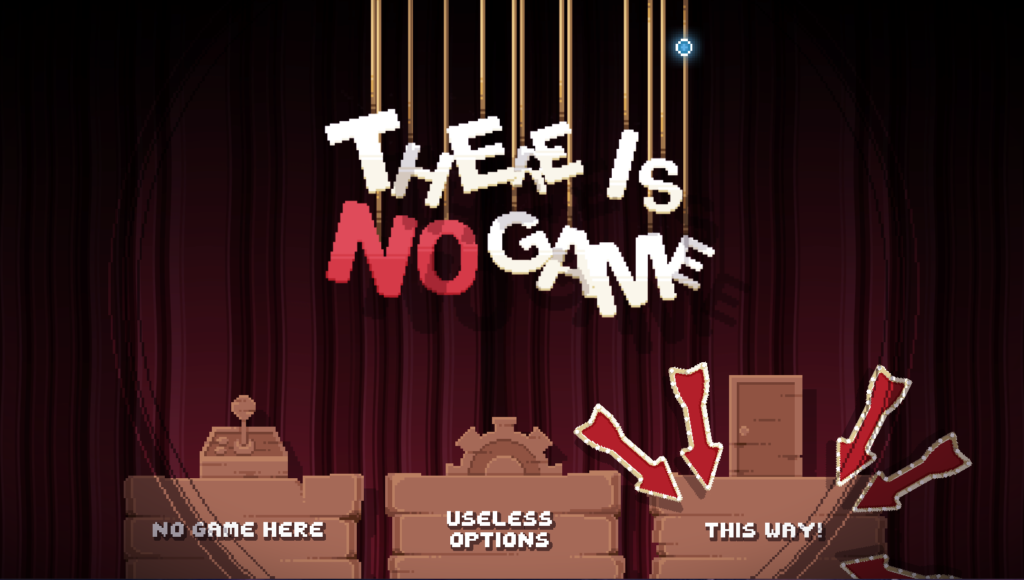

Two of my favorite videogames that fall within the metagame category are Oneshot and There is No Game: Wrong Dimension. Both titles break the forth wall and communicates with the audience effectively, though through drastically different means. Of the two, There is No Game takes a lot more explicit approach. In its first few screens, the game sets up a narrator, who communicates with the player directly through audio and on-screen interactions. Throughout different levels, the player is always the one driving the game. We are involved in the production and decomposition of game worlds, each corresponding to a different style and genre of games (i.e. puzzles, rpgs, etc.). The player interfaces with different elements on screen in a point-and-click style. This allows for the game to comment on these genres without making it explicit in the narrative. There would be no game without the player.

Oneshot tackles the metagaming genre in a materially self-reflexive manner. The protagonist, Niko, is guided by the player. In most parts of the game, we can influence her by picking different “dialogue” options. However, in later parts of the game (without going into spoilers), the player gradually loses control over Niko and the world. It is revealed that the world is controlled by an entity who messes with the player in different ways, including altering files in the player’s documents. Oneshot integrates the player’s and Niko’s world in an organic way. Unlike in There is No Game, where the player simply stirs trouble in the narrator’s world without any repercussion, Oneshot establishes a two-way connection. In Oneshot, the world is truly dynamic; the characters can act on their own behalf; the antagonist reaches into our world to fight back, and things are partially or completely outside of our control. This allows for the player to question their absolute power as a guest in the game world, and radically changes traditional presentations of the player-game relationship.

Different as the two games are, they are both considered metagames. In both cases the player is led to scrutinize and question the medium of videogames. They are videogames about videogames. It is their reflectiveness that makes them so brilliant.