Minor spoilers for Doki Doki Literature Club, Batman: Arkham Asylum, Final Fantasy IX, Phoenix Wright Ace Attorney: Justice for All, and Santa Claus as a concept.

A discussion we touched on in class that I find myself lingering on is that of the “magic circle.” A magic circle, in the realm of virtual worlds, is the extent of the imagined play-space where the game takes place. In essence, if I am, for example, playing with a play-house and a baby doll, in actuality, both of these items are plastic- they may superficially resemble a house and a child, but take on none of the responsibilities or properties such objects hold in the real world. Within the “magic circle” of the plastic house, however, I and my playmates confer imagined properties to these items- we pretend that there is a floor in the house so there is meaning when we remove our shoes, or that the plastic doll responds to imagined food in a plastic spoon. This concept applies as well to video games, where the magic circle must be understood to cover the mechanics and rules of the game- we understand the avatar to “be” ourselves, so closely that players will often say “I died” rather than “the avatar died” or “Link died,” and some even say “ow” when they are hit in a game (myself included). Players also understand that game mechanics are symbolic of something greater than the literal- glowing blue orbs in Xenoblade Chronicles are representative of items the player can pick up, and relationship meters or ranks such as in the Persona or Fire Emblem series represent degrees of closeness between the two characters rather than being a literal number. None of these items are what they appear physically to be, whether plastic objects or numbers, as our suspension of disbelief dictates that they are more.

“Suspension of disbelief” is a literary term I believe to be closely related to the concept of the magic circle. It was originally explored by Aristotle, who used the term to apply to theater, which is its own magic circle of sorts- we imagine that the sets are real places, and that the actors are truly the characters they embody. However, while the two terms are linked, the magic circle actually permeates deeper than simple suspension of disbelief- American philosopher Kendall Walton skeptically argues that suspension of disbelief is not wholly achievable the vast majority of the time, as people emotionally respond to fiction, but do not truly act as though the events were real– those watching horror movies, for instance, will not flee the scene or call 911, because they ultimately experience separation from the events of the film.

In the magic circle, however, players are forced to physically react to events- in a horror game, rather than a horror movie, when faced with a threat, players can indeed flee the scene, and even must do so in order to progress. They still know that the events of the game are not real- that they can turn off the game console (in some cases- I believe some metagames such as Doki Doki Literature Club can disable exiting the game, and Batman: Arkham Asylum implements a fake game crash, though I haven’t personally played either so I may misremember) or physically walk away altogether. However, the expectation and capacity for physical response heightens the reality in a way simple suspension of disbelief cannot.

Thus, I will attempt an answer to the question posed in class: in a world with incredible amounts of content relating to video games (including mods, strategy guides, and more), where does the magic circle end? My argument is that the magic circle exists insofar as suspension of disbelief does- that the magic circle is more a state of mind than a physical arena like a game board. This means that it is highly dependent on each individual experience, but I believe it must be. The magic circle for Pokémon Go, for example, has no limits but cellphone service and land boundaries, yet although I live in an area where it might be played, I would not consider myself a part of the magic circle. I do not own or interact with the game, so I cannot suspend my disbelief that Pokémon I cannot see or detect roam the streets. I could be a part of someone else’s magic circle, however, if I am standing in front of a Pokécenter, and thus become an unwitting obstacle in the game world- with in the context of the game, my presence takes on new meaning.

This means that if someone chooses to employ mods in their game, these mods become part of the magic circle for them and others who use the mods. If the individual is willing to suspend their disbelief that, for instance, there is an additional aquarium mechanic in Stardew Valley, or that Beatrix joins your party in Final Fantasy 9 (I wish…) or that every dragon in Skyrim is replaced with Thomas the Tank Engine, these developments become intertwined with play. They are diagetic additions to the game, incorporated seamlessly into the game-world. Wikis, however, are not part of the magic circle, because they are out-of-character. The Stardew Valley Wiki speaks about game mechanics forthright- if it were part of the magic circle, it might say something like “farmers should make sure to pet their animals. If you pet your cat or dog every day, they will start to love you more. Being friendly with your cat or dog could lead to benefits in the future!” rather than “the pet has a maximum friendship of 1000, increasing by 12 every time it is pet. Every 200 points is equal to 1 level, and having 999 friendship points will make the player eligible for 1 point in Grandpa’s Evaluation. Click on the pet once each day to pet it.” “Points” do not exist within the diagesis of the game, but rather are a mechanical representation of the “pet relationship” concept, a quantifiable value to express to the player how much the pet loves them. This is akin to referencing the fact that the baby doll is plastic.

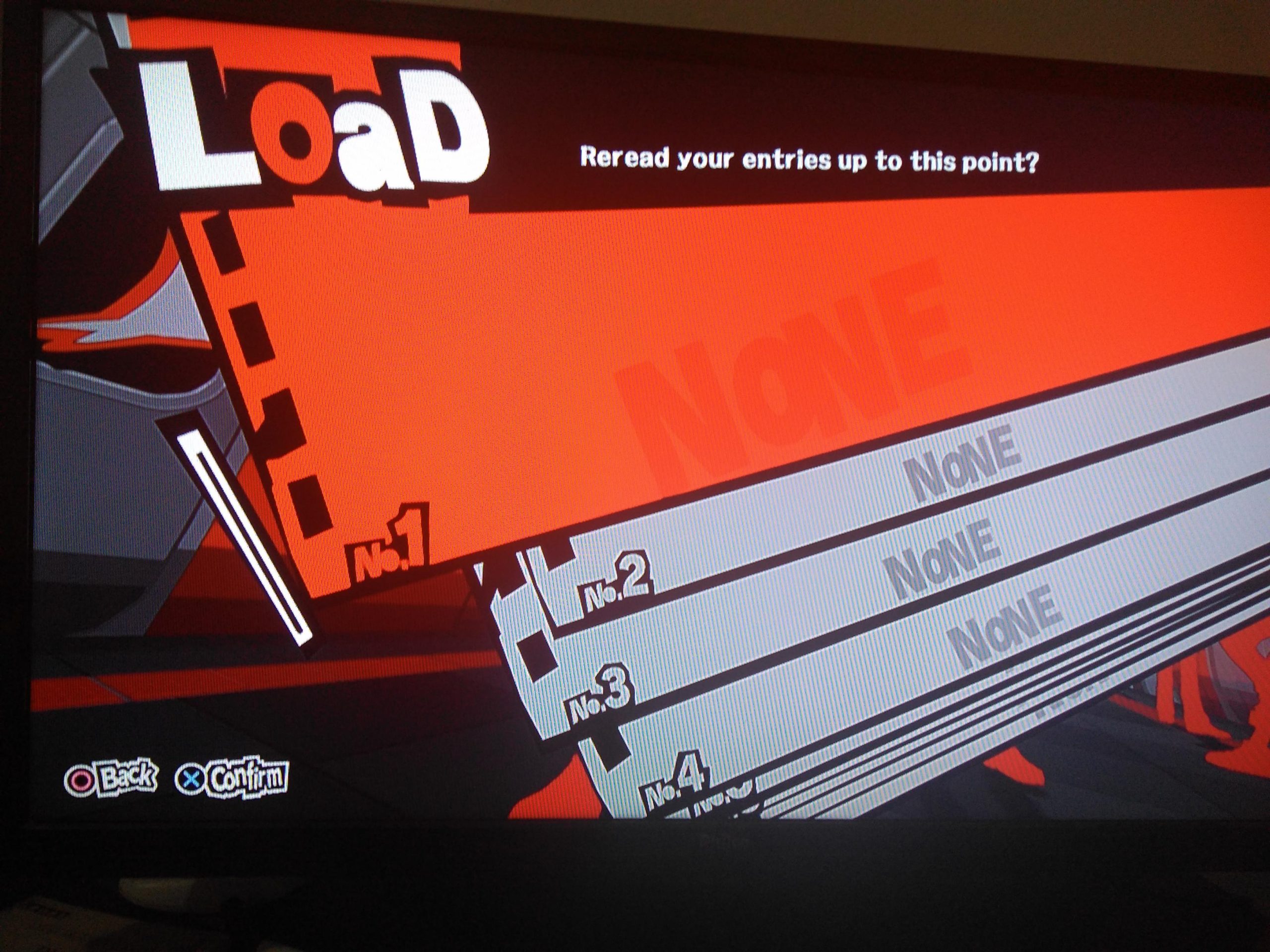

In light of these claims, I would now like to pose two questions I’ve been considering: firstly, how important is immersion in suspension of disbelief? I am intrigued by situations in which the “magic circle” is broken by the game itself, inspired by the game we played for class today, Dys4ia. The game was buggy and at times unplayable for much of the class, myself included, yet many of us had different “breaking points” where the magic circle ceased to function. One classmate noted that he believed the waiting section was simply 5 minutes long, rather than “exiting the magic circle” and assuming that the game itself had broken. Many modern games even employ interesting “suspension of disbelief” explanations for times when the game might exit the magic circle. Saving is an action that necessarily brings the character “outside” of the magic circle and into non-diagetic menus, yet Persona 5 tells us within the magic circle that the protagonist is recording his experiences in his parole diary when we save. In Xenoblade Chronicles, the aforementioned literal interpretation is that the player picks up glowing blue orbs containing items to increase their inventory, but within the magic circle, the item descriptions often reference that the science-curious main character is occasionally picking up samples to study, and the rest of the party is helping to name new plants or animals they find. Thus, the game contextualizes the player’s desire for money or solutions to future quests as the main character’s own intentions. Final Fantasy 12 contains teleportation devices in the world of the game to explain fast travel within its magic circle. Many games incorporate the tutorial as the main character learning or reviewing different actions, such as the Phoenix Wright Ace Attorney series, where every first level contains a new lawyer character learning the rules of court, with the exception of the second game where Phoenix hilariously gets amnesia. Are these examples of additional immersion which create stronger and more steadfast magic circles, or are they unnecessary insofar as players must know the game-world is not real, as they must take actions outside of their suspension of disbelief to play the game at all (i.e, turning on the console and controller, pressing buttons)?

Secondly, how important is simulated realism in the experience? A fascinating development in the modded magic circle of Skyrim and Fallout 4 are the immense prevalence of “immersive” mods which implement basic functions into the game, such as a mechanical system for eating, sleeping, and even using the bathroom. Does this addition increase the immersive power of the game, and the suspension of disbelief that the player is a real human in the same way that a baby doll with a speaking function or blinking eyes might? Or do they “gamify” basic functions in an inherently unrealistic way, and even break the suspension of disbelief by reducing complicated functions like nutrition to a single hunger bar?

I found this post fascinating – especially when you touched on the exceptions to how video games typically use magic circles (namely, Batman: Arkham Asylum and Doki Doki Literature Club). How these games played with the player’s expectations of a magic circle popped into my head during the discussion about the concept last class, but I couldn’t really put it into words. And even if I could, I don’t think I would be able to make my point as succinctly as you did, with: “However, the expectation and capacity for physical response heightens the reality in a way simple suspension of disbelief cannot.” I completely agree with this point and believe that is a big reason why these moments from those two games are so scary!

I found your discussion of “saving” as a mechanic that brings a player outside of the magic circle particularly interesting. It made me consider how saving can disrupt a player’s entrance back into the “magic circle” (ie. if you forgot to save, if your data is erased, or in a game like Animal Crossing: Wild World where a diegetic character will address the fact that you didn’t save). Particularly in the instance where the data is not saved, I believe the player’s “suspension of disbelief” is jeopardized. Personally, when this happens to me in narrative based games, I feel as though this technical setback puts me in a liminal space between the “magic circle” and reality; I must passively B-ing through everything I have already seen before I can begin interactively immersing myself into the game. When players are forced to confront the limitations or faults of the medium they are engaging with, I think important questions emerge about where/when “play” begins. Am I really “playing” within the “magic circle” when I am speed-running through cut scenes to get back to where I left off?

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this blog post. I specifically enjoyed the section where you describe Pokemon Go’s relationship to the concept of the “magic circle.” I hadn’t thought of augmented reality games in that way before reading this.