Many of the serious and educational games that we’ve talked about this week aim to teach the player more about a certain life experience by simulating it in game form. This is the case with games like Spent and We Are Chicago, in which the player tries to embody someone living in a difficult situation. These games want the player to empathize with the characters that they play as and interact with. I think that thy are initially successful in this goal, however the way that they are structured leads many players to focus on optimizing their play and getting the best possible results.

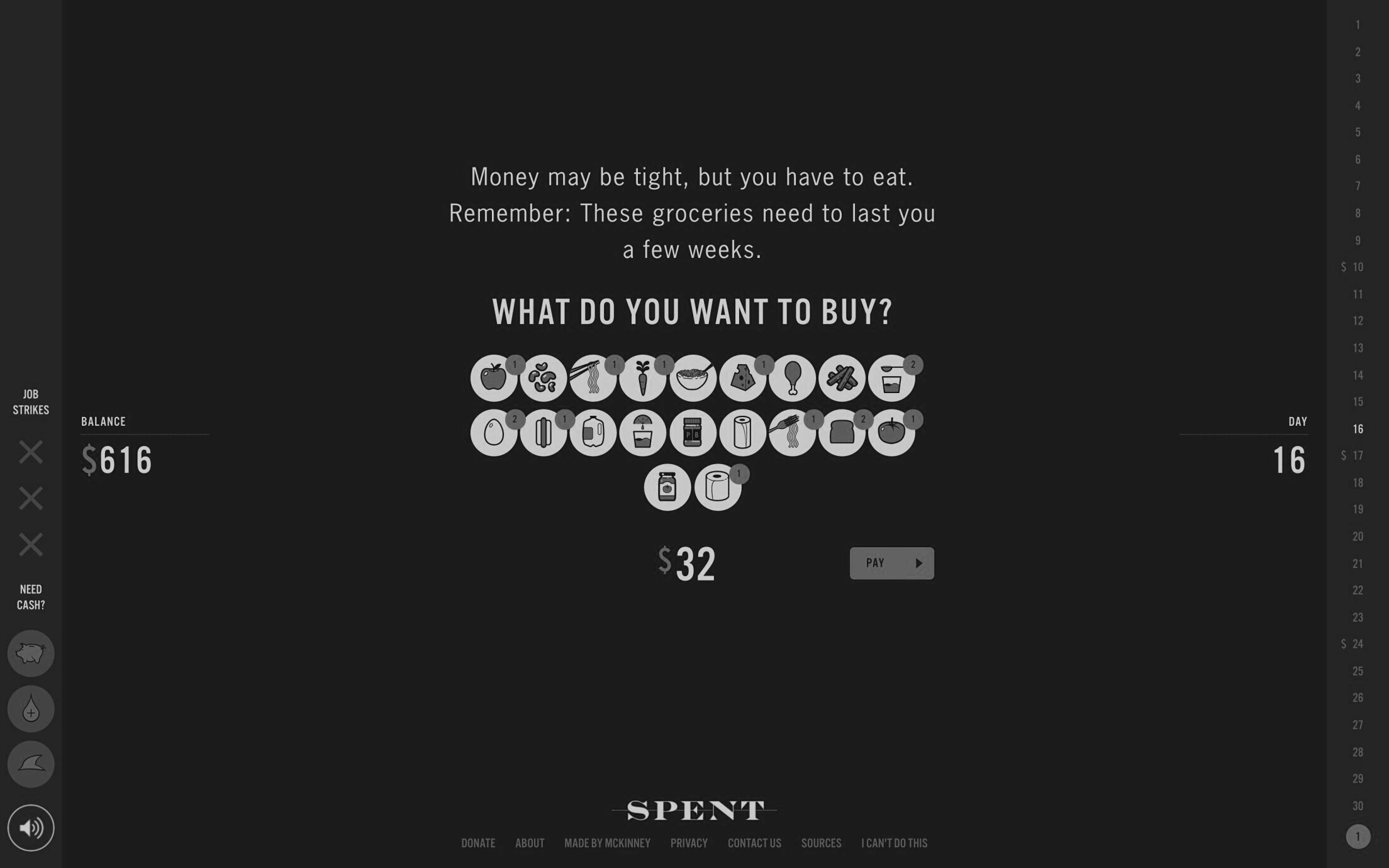

When I played Spent the first time, I barely made it two weeks before running out of money. It made me think about how difficult the experience had been, and how reflective it was of the shoestring budget that many Americans live on every day. However, I hadn’t seen much of the game. My curiosity drove me to uncover the rest, so I replayed it – and I nearly won. By my third playthrough, I knew what choice to make in most encounters and was able to survive the month with a positive balance. Had I chosen to continue playing for much longer, I probably would have known the right decision to make in every interaction in Spent. Once I was able to complete the game this easily, I found myself taking it less seriously. The message I had initially gotten seemed less poignant now that I knew how to beat the game.

I didn’t play We Are Chicago, but its structure seems similar. There are a variety of “good” and “bad” outcomes to most decisions, and for the game. Since the game is short, a determined player would have little trouble optimizing their playthrough to achieve the best possible ending.

Of course, this kind of replayability is not realistic. Low-income families cannot try the same month repeatedly until they manage to end with a positive bank balance. High schoolers cannot repeat an interaction with a friend until they get the best response. Allowing players to get the same exact results every time they play through the game removes the factor that makes the initial game experiences so stressful: uncertainty. When the player knows the exact consequences of each possible decision, gameplay seems easy and intuitive, which is exactly how it is not supposed to feel. This replayability undermines the goal of these games, which is to make the player feel stressed and uneasy and to make the environment seem deliberately unfair.

I think that if a narrative game seeks to communicate what it is like to live an experience difficult from the player’s, uncertainty is one of the most important factors to accurately communicate. Games can do this by making themselves dynamic, finding ways to not generate the same outcomes every time they are played. For instance, certain decisions in a game could lead to multiple risk-based outcomes instead of a single outcome. In Spent, this could take the form of risk associated with saving money. Instead of a predetermined event where the character feels ill, there might be a random chance of illness, with a randomly determined consequence if the player opts to save money by avoiding seeing a doctor. Finding ways to change the narrative and make replays less reliable can maintain the sense of stress and unfairness that games like Spent are aiming to impart to their players, which will make their messages resonate more strongly with those who replay their games.

Image Credit: https://www.whitenoiselab.com/interactive/spent

I think that you have a really great point. I think this conversation can be continued by considering all game genres more broadly. In many games outside of the serious/educational genre, players may often save their gameplay right before a boss or another difficult point in the game in the case that—should they fail or not achieve the desired outcome—they can repeat that section of the game immediately until they succeed. And while completing gameplay and then attempting again is not exactly the same because it is not immediate, I think it carries the same sentiment. Games are games, and unlike life you can facilitate do-overs.

Over the course of this past week, I have been thinking a lot about a question that you touch on in your post: how do game developers help a player to better understand difficulty and hardship when the player’s method of interaction (pressing buttons, moving joysticks, etc.) is often much easier and more accessible than the mechanics or actions they represent — e.g. in Spent, you purchase groceries, pay off debts, and avoid fines by clicking on a few icons, but the real-world actions/processes these things represent are much more laborious. I think that this, along with the ability to replay the game, might be one of the reasons why the developers of Spent did not see the results that they might have hoped for as makers of an educational/serious game. I know that the Kaufman and Flanagan reading/study addressed this in a way, but I would be interested to see an analysis done specifically on how playing a game that involves/represents a certain action or event affects the player’s perception of the “real-world” difficulty of that action or event.

I think your post is doing a great job of thinking through how games like Spent are caught in a bind between creating moments of uncertainty and driving home how inevitable hardship is for low income families. Personally, when I played the game, I managed to make it through the month on my first run, and this left me with the profound feeling that I had just gotten lucky. But, I think this outcome could have caused another player to feel that, as we were saying in class, poverty is all about making the right choices and that ultimately, you are in complete control of your situation. I would be curious how changing this game so that a player could never make it through the month would impact the component of “uncertainty.” I think if the player didn’t know it was impossible to make it through the month, it could create an interesting replay situation where the player desperately goes through trying to make their choices mean something, only to be confronted with the reality that individual actions are not always equip to fight systemic issues.

Though in large I do agree with you that predictability can make a game feel too easy on subsequent runs, randomness runs the risk of swaying things in the opposite direction, particularly if you only play it once. When you introduce randomness into a situation, if the outcomes are all similarly bad, or a situation that has a certain chance of occurring at any time is guaranteed to happen at some point, it defeats the purpose of the randomness because the events are still essentially guaranteed. On the other hand if you have chance for events of varying severity, you run the risk of leaving people thinking that they only lost due to extreme bad luck rather than actual difficulty, or even worse gives them the chance to actually succeed by luck because they got the only somewhat bad options. Though I do think randomness would lead people to the failure state more often, I’d worry that it could lead to some people taking home messages even further from the intention.

Your post makes a great point about replayability undermining the game’s educational purpose! And the discussions in the comments are all very interesting. This reminds me of a similar point brought by the reading in horror game week, which says that the horror of the game can be undermined by gameplay and the player’s desire to win. E.g., If you are just busy finding a save spot, you will be distracted and not be as immersed in the horrifying environment around you as you are supposed to be. Thus this makes me wonder: are games really a suitable educational medium for mediating people’s difficulty and teaching lessons (maybe) to players? Or what kind of games are more effective in achieving such a purpose?

I was reminded of Hair Nah, which was a pretty short and simple game. But it was pretty effective for me in terms of being an educational game: the message at the end hit hard and actually let me be more aware of and sympathize with this annoying daily experience that could happen to black women. The game presents a difficulty that you can kind of overcome at first, but will not be able to overcome fully in the final round (when there are simply too many hands and you are expected to not be able to defend yourself against each of them). There wasn’t much replayability to Hair Nah, though admittedly you can replay it, the game didn’t present a clear goal for you to replay it. So learning from Hair Nah, some programmed difficulties that are not supposed to be solved by player action could be an effective representation of real-life difficulties, and its lack of replayability (which is to say giving all the content at once) might help the players be more impressed with the message (like, the message may hit harder than if the message is diluted in multiple rounds of playing?).