For this blog post, I want to briefly discuss how the inclusion of images in text-based games (like visual novels, interactive fiction, etc.) contributes to or disrupts the gaming experience.

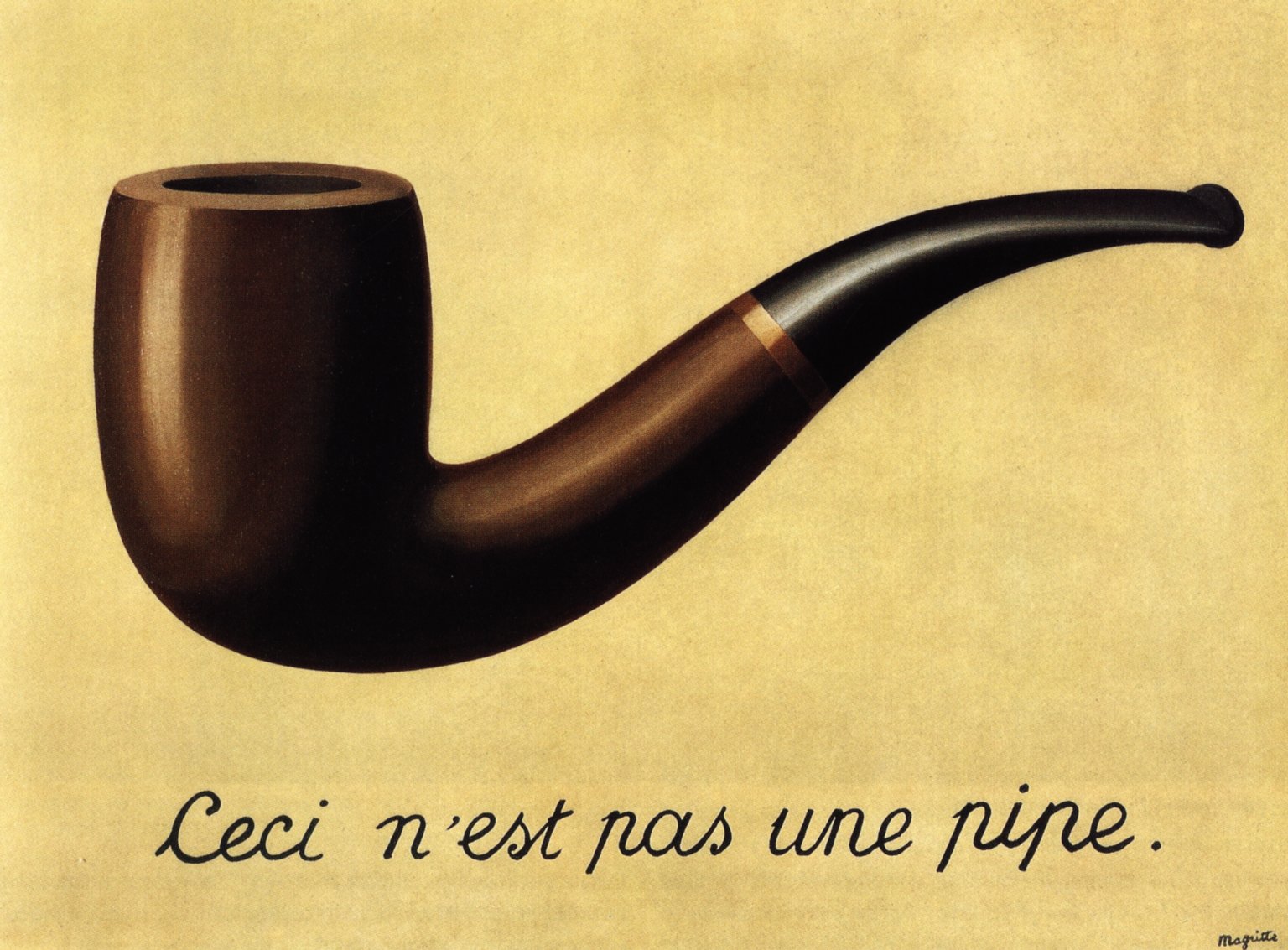

To begin with, a related background theory is Saussure’s construction of language as linguistic signs. A linguistic sign consists of two essential elements: the signified and the signifier (Saussure 66). The signified means the concept represented by this specific word/sentence, “what is signified by this word”. e.g., the word “pig” signified a pig, so that when we read it, we know what these 3 letters are referring to: “an animal that has a large head with a long snout that is strengthened by a special prenasal bone and by a disk of cartilage at the tip. The snout is used to dig into the soil to find food and is a very acute sense organ. Each foot has four hoofed toes, with the two larger central toes bearing most of the weight, and the outer two also being used in the soft ground” (Wikipedia “pig”).

The signifier is the thing that is used to represent the concept, e.g., the word “pig” is a signifier used to signify pig. This word is associated both with a sound, the pronunciation “/pɪɡ/”, and also the image of a pig, how a pig looks like. So, a signifier is essentially a sound-image. And a signifier (sound-image) plus a signified (concept) is a complete linguistic sign that forms our language. Our language also functions according to a constructed conventional understanding to a large extent. E.g., when we say pig, we assume that we all know what pig refers to so that we can further build conversations on these concepts without having to explain what pigs mean every time.

However, conventions are not stable, and each individual will have their nuanced interpretation even for the same signifier based on their experience and language habits. E.g., when talking about a pig, person A’s default association might be a small and cute pet pig, while person B might think about a huge pig in the barn. When talking about more abstract concepts like love, the variations will be even larger.

This crack of instability is where the inclusion of images comes in and adds the complexity of the gaming experience. A pure text-based game like Galatea bases its creation and diversity entirely on the players’ personal “signified”. Each player may have a slightly different image of what a hallway in the museum looks like, or placard, etc. In this way, the variation of the games is not only in terms of different orders the players give, but also how they perceive and understand the same given text. So, each player will essentially have a unique gaming experience starting from this micro level. But pure texts require more literacy and comprehension ability from players, which could be a potential obstacle. On the other hand, visual novels that included heavy use of images somehow hindered these nuances, because the inclusion of image is essentially designating a standard “signified” and telling everyone that this is what this concept/word should be referring to. E.g., Diya should be imagined this way, their way to school should be imagined that way, the stadium looks like this, etc. It makes it more difficult for players to develop their own imagination but is useful for fostering a common understanding of the story.

Balancing these two sides, how can game designers make good use of the inclusion of images in text-based games? What effect will it have if we redesign the same game in the other way, say, making Galatea a visual novel while taking away Butterfly Soup’s images?

Works Cited

Saussure, Ferdinand de. Course in General Linguistics 1959 [Hardcover]. Facsimile Publisher, 2021.

Wikipedia contributors. “Pig.” Wikipedia, 22 Oct. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pig.

I think the last question you pose is interesting, because I believe that both games could have the potential to be either a visual novel or interactive fiction; in fact, I think that if Galatea had images, the message the game is sending would be even more evocative and if Butterfly Soup was entirely text-based, the story would still be expansive and detailed. However, in the scenario of switching form, would the agency in choices still be the same as it was in the original version of the game or would the ability to pick choices/routes have to change alongside the form of the game itself? Like if Galatea became a visual novel, would the player still have the ability to type in commands or would Galatea have a limited amount of choices that the player chooses from? At that point, I feel like the games themselves would be entirely different games and have maybe the bare bones of the original. It is just interesting to see how different forms and genres of games could impact the actual game itself and how much of the narrative would have to change to fit the new format.

This post really changed how I think about images! I think the idea that different people can have different mental images of the same thing is very interesting, and the way that imagery can build on or exploit that is very cool. I think that not including images in a game is still a significant choice – just as much so as choosing to include them. An imageless game leaves more up to the player’s imagination, asks them to interpret the text they are given on their own, rather than holding their hand through it. I think that’s why Butterfly Soup has images and Galatea doesn’t. Butterfly Soup has a pretty specific story it is aiming to tell, and its images help to accentuate the story and make it clearer to the player. Galatea, on the other hand, is more interpretive. The player guides the story with different dialogue and action choices, so it makes sense that the game wants the player to also be able to imagine the setting for themselves.