It has been my second forced relocation in 48 hours. Now situated in a stark, sterile, white walled box, I finally take a moment of pause. Solitary. The sole window is ajar, allowing for the semi-humid, crisp night air to accumulate on my recently unmasked skin. I realized then, that I could never smell the rain. A single pillow and sheet have been adorned on the twin mattress crammed in the corner, but any remaining furniture, save for a desk and chair, have seemingly vacated the room. Bare. My worn, hastily packed suitcase is set on the floor beside me, its ribbed handle still imprinted on my hand following the abrupt relocation from a prior space that I, once again, never had the opportunity to call my own. My laptop whirrs away, its jagged steel outline disrupting the otherwise barren landscape of the desk. Its screen harbors a low-poly entity, drifting aimlessly among a spattering of makeshift stars. Spinning. A chime then cuts the silence, fading as abruptly as its interjection. Text. “I’m lonely”. Mountain continues to move, circulating around its vast ever-expanding world trapped within the confines of my computer. Isolated. A quiet overtakes my room as the meaningless drone fades, Mountain growing ever more distant and a deep, constant thrumming is all that remains. My only response, spoken to briefly fracture the semblance of encompassing silence: “Yes, Mountain. Yes I am.” Lonely.

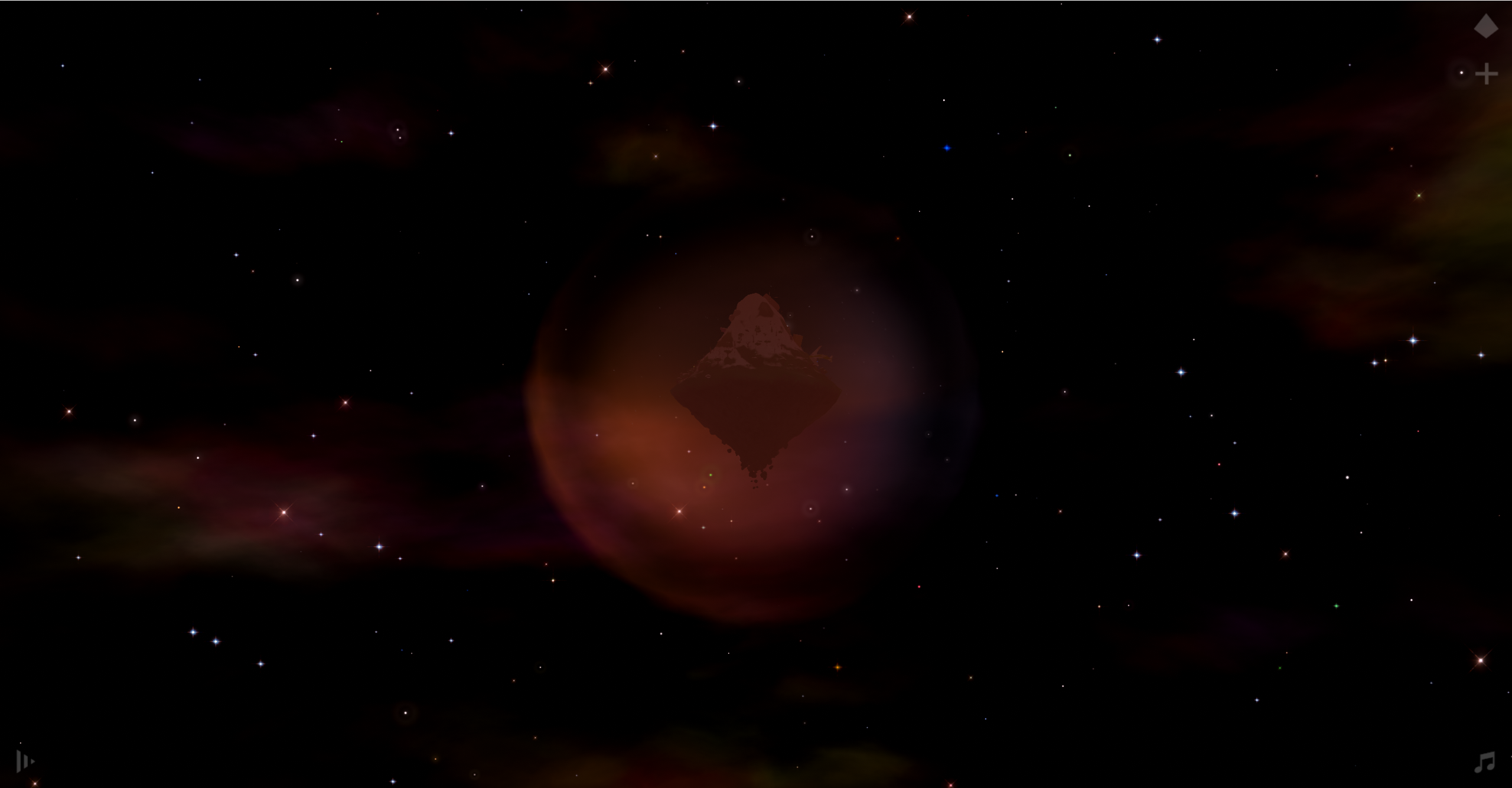

Mountain, developed by David O’Reilly, serves as a self described nature simulation game through which a Mountain takes residence within your chosen device. Upon launching the game via a pixelated image of a low-poly octahedron, you are greeted with prompts by which to crudely draw whatever pops into your mind. The prompts themselves grow increasing in complexity, and I fully admit that my attempt to represent “mercy” through a trackpad-scrawled image of stick-figures was less than touching. Then, however, the real premise begins. Before you a floating mountain appears, suspended within a spherical atmosphere where particle clouds dance and various trees dot the conical landscape. “Welcome to Mountain. You are Mountain. You are God.” A greeting text is paired with a resonant chime, and it’s one you will grow familiar with throughout the game. There are natural events, your Mountain’s foliage takes on seasonal hues, objects may collide with your Mountain, you discover (perhaps accidentally) that you can play music, and you might even proceed to watch as a storm of frogs descends upon your little floating realm of mass when you play an atmospheric rendition of ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” on your keyboard.

Past that, however, there is no further game. You do not progress, Mountain doesn’t grow in physical volume – save for the oddly sized objects that careen into its surface with a satisfying thud. Its thoughts do not grow more complex, nor can you revisit any past thoughts it might’ve materialized. You can’t ‘unlock’ new songs or edit how Mountain specifically choses to change its lovely colors. It, simply, just continues to exist.

So, knowing the entirety of the game, how would you categorically define Mountain? I, for one, believe its beauty is found in its inherent intersection between it being both a game and a passive interactive art piece. The technical definition of a game is “a form of play”, and Mountain’s genre revolves around a mode of an idle game. I feel, however, that Mountain actually serves as a loosely derived, self-imposed narrative game through which the player defines their mode of play within the provided mechanics. Some may view this as management, organizing and rearranging Mountain until it satisfies their Marie Kondo dreams. Others might appreciate the achievement aspect of the game, running through codes and idling the game to gain all the potential Steam achievements. Groups might even feel collectivist, scouring the internet for a list of all potential objects and weather patterns to accumulate on Mountain.

Yet, with other idle games like Egg, Inc and Cats & Soup, the linear progression is clearly outlined by the game, and your experience within the game is directly and irrefutably tied to how much time you put into it. You have the illusion of choice, but in the end you simply need to wait to gather enough of some currency by spending time idling. Overtime, yes, your community grows and you have some modicum of influence over the species of cat or the color of your chicken eggs, but you can never truly change the game via exploratory methods. With Mountain, however, it simply exists. Mountain doesn’t need you to micromanage it, you simply must serve as a silent observer. Mountain has never demanded my time. Mountain does not care.

I believe the genius of Mountain is not found in its ability to represent the human experience, but rather how its experience is distinctly developed depending on its humble God, that being the player. Upon initially reflecting upon the game, I loved the metaphorical aspect of Mountain, as it seemed to serve as a reflection of the human experience. Various “junk” may accumulate, and despite how you might decide to rearrange or compartmentalize these facets of your life, they will always find a hold. You can play music, appealing to yourself while watching Mountain dance to its newfound erratic weather. You can strategically shake off weather clouds or release the accumulating objects back into space. You can even choose to destroy Mountain, sending a mass of pulsing polyhedrons careening to its surface to then frantically decide whether Mountain was really worth saving. “You are Mountain”. You, the player, are inexplicably tied to the thrumming entity within your device.

Mountain serves as a unique, profound experience that differs vastly for each player. Coming at a time where I experienced uncertainty within my life, I felt it was reflected, and in turn I felt seen, by the disorganized chaos and randomness that is Mountain. It gave me a medium through which I chose to define my mode of play, within this system choosing to compartmentalize, experiment, organize, and then destroy the ever-present octahedral mound that resided within my laptop. Yes, Mountain is a piece of idle art, but I believe players will find solace in the stance of the silent observer, simply allowing Mountain to be.

I want to end with a poem of sorts, plastered on the singular arcade-style rendition of Mountain produced following the initial release of the game. It reads as follows:

You will not see me

But look at the Mountain

If it should remain in place

Then you will see me

Your writing is very beautiful. I agree with you that a great part of the magic of Mountain comes from it being an interactive art piece, which creates an experience really different from more conventional game play.