Prior to our discussion on Doki Doki Literature Club in class, I decided I wanted to do something special for what I believed was my 3rd playthrough of the game. Normally, if I’m given the option to play a game that is either free or offered at a cheap, discounted price, I would immediately take that in a heartbeat before you could even give me a second option. However, considering how much I love this game and how impactful this game’s story was for me, I instead chose to buy the $15 version, which is titled Doki Doki Literature Club Plus. Both versions of the game are pretty much identical in terms of visuals and gameplay mechanics with the only real difference being that Doki Doki Literature Club Plus has six additional side stories that are unlocked after you beat the game’s main story.

These side stories take place in an alternate reality of the game in which the Protagonist does not exist and it is assumed that Monika has not yet had her epiphany that she is not real and just a character in a video game. Through these stories, the player discovers not only how the Literature Club was formed, but also how each member became friends with one another. Each side story focuses on a pair of characters at a time, and what makes each of these stories incredibly effective is how well they are able to flesh out each character’s personality, backstory, and most importantly their inner demons. Whether it’s Sayori’s depression, Natuski’s malnourishment and abuse, or Yuri’s susceptibility to inflict self-harm, each of these thematic elements that were explored in the main game are even more fleshed out in the side stories, and through each story, each member attempts to overcome their demons by learning to open up to each other with Monika serving as a sort of guide for each character. These side stories showcase just how important these characters are to each other and that they will always be by each other’s side… yeah, about that.

![Doki Doki Literature Club Plus] Sayori and Monika How They Met - YouTube](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/0059VUANs9Y/maxresdefault.jpg)

The point I’m trying to make about these side stories is that in an alternate universe of the game, a universe in which “we” the players do not exist, the characters in the game are able to live happier, more fulfilling lives. Sure, the inner demons they had in the main game are still present, but without our presence, the characters are able to talk to one another about their problems, and by doing so, they allow themselves to be on the path of overcoming their struggles and ultimately become healthier, happier people. In an alternate universe where “we” the players do not exist, Monika does not have her epiphany that she’s in a video game, which not only prevents her from feeling such extreme depression and loneliness but also doesn’t drive her to kill off every single character for some twisted sense of love. In the main game, every character dies in gruesome, horrific manners, all for the player’s unrequited love because they were programmed to prioritize your affection for them above all else, and if they can’t have it, then what would be the point?

This is one of the subtle horrors when it comes to a dating sim: the objective of a dating sim is to woo a character into becoming your partner, and most of the characters’ purposes in a dating sim is to express love and affection for the main character. However, if their feelings with the MC aren’t mutual, then imagine the kind of pain and stress that could cause: their only purpose is to be selected to be the MC’s partner, and if their purpose isn’t fulfilled, then what is the point of their existence? These are the questions Dan Salvato explores in Doki Doki Literature Club. The characters in DDLC are not stable people, they all have inner demons that are eating them up inside (as seen in the side stories), so as the player continues playing the game and does all the cliche, generic dating sim tropes, it takes a toll on the characters to the point that every single one of them dies in gruesome ways, regardless if you confess to them or not.

However, the horrors of being in an anime dating sim take the biggest toll on Monika, someone who despite being self-aware of the fact that she’s in a video game, is frustrated that she herself can’t be a romantic option for the MC, which drives her deeper and deeper into insanity to the point that she commits all those unspeakable cruelties that happen in the game. However, the worst of it is that when she finally gets to spend time with us, when she finally gets to be with her “one true love”, we reject her, we erase her character file, which not only serves as a stab to the heart for her, but she also comes to this self-realization that the game she is in has no sense of happiness. No one can be truly happy, so she decides to just shut it all down, all because every one of the characters is programmed to be madly in love with “us” the players.

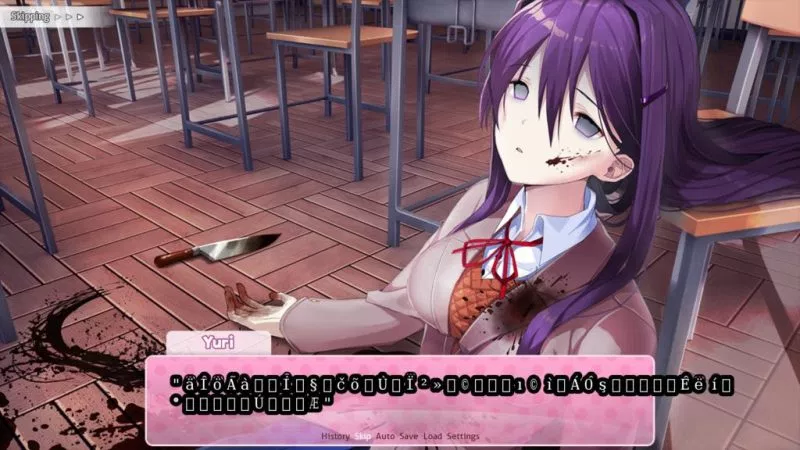

This is where I come back to the side stories I mentioned in the beginning. In an alternate universe where “we” the players don’t exist, the characters are able to live their own happy, self-fulfilling lives. They are able to control their own destinies, and most importantly, they are able to overcome their personal demons through their close and strong friendship with each other. It was when I played these side stories where I truly realized that “we” the players pretty much ruined these girls’ lives. It was because of our forced inclusion in the game that all the crazy, insane stuff happened. Each member of the literature club was already going through dark emotions, and to now force them to fall madly in love with us because they happen to be characters in an anime dating sim only drives up those dark emotions. If “we” the players didn’t exist in the game, then none of those horrific events would have happened. Sayori wouldn’t have hung herself, Natsuki wouldn’t have bled tears and bent her neck, Yuri wouldn’t have stabbed herself, and Monika wouldn’t have started all this horrific nonsense in the first place.

These characters have a chance at actual happiness, and “we” the players ruined it by forcing our existence on them. It doesn’t matter if we want what’s best for them. By simply existing in their world, we have fundamentally ruined their lives, and I don’t know about anyone else, but that just makes me feel like a bad person. Sure, you could theoretically get the “good” ending of the main game by spending time with each character before Sayori hangs herself, but Monika still has to suffer in the end because of her epiphany. No matter what, someone will be scarred by the end, and it’s all our fault. Monika is not the true villain of Doki Doki Literature Club. We are. We are the true monsters because our very inclusion is what jumpstarted the events of the main game. These characters are much better off without us, and if you truly want the “best” ending of Doki Doki Literature Club, it’s best to just not play the game at all… but then again, you probably will anyway.

This blog post offers us an well-rounded summary of DDLC Plus and gives an inspiring perspective to think of our relationship with the video game characters. One thing I want to ask after reading your post is, by sharing these side stories of the girls, does the game help weaken the centrality of players? Like you said, players forced into the characters’ lives and evoked their demon, then would knowing that it is the player’s presence that turn these girls against each other further satisfy the player’s sense of dominance and reinforce what players are expected to get out of a dating sim? I can’t agree more that DDLC is a game which aims to challenge implicit gender dynamics and gaming traditions embedded in dating sims: at the end when we were finally forced to sit alone with Monika, she told us she knew why we were here and what we expected to get out of this game and out of them, and every setting here complied with our own imagination, no matter how weird they really were (eg. cute girls in Japanese suits speaking English). Then, does DDLC Plus further speak about the claim DDLC wishes to make, or does it head in the opposite direction?