It is a common misconception that the writing of history simply entails recording what happened in the past, and that the role of the historian is nothing but a courier that carries history to the present and deliver it without any intervention. The process of history involves an active process of selecting and analyzing parts of the past that are to be written down, and the writing of history itself – historiography – is a process of subjective interpretation and presentation. In completing a play-through of Return of the Obra Dinn from start to finish and thus experiencing the entirety of the narrative that is constructed by Lucas Pope, and reflecting on the in-class discussion we had on the subjects of colonialism and insurance, it struck me how the game, despite its fantasy elements, is very comparable to the more traditional historical narratives in literature.

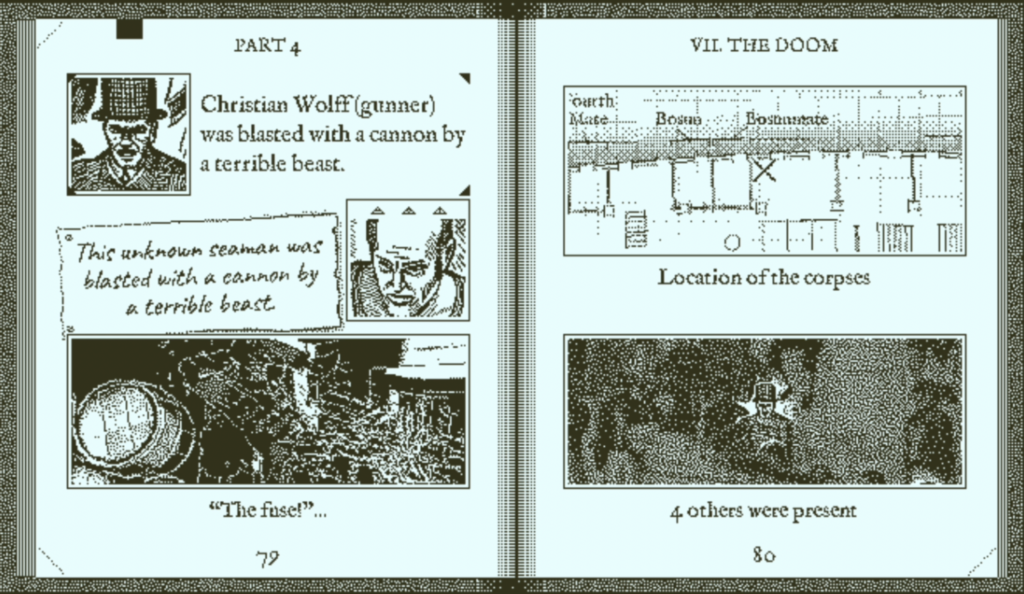

One aspect that is particularly noteworthy for me is how Pope uses the core mechanics of this game for the purpose of constructing a historical narrative. In Return of the Obra Dinn, it could be said that the most important mechanic of the game is problem solving in figuring out the identity of each of the members of the crew on board the Obra Dinn and determining their fates. It is through the centralization and emphasis on this mechanic that allows Pope to construct a myriad of historical details about the British East India Company and its operations on a ship in the early 19th century and to condense them all into the space of the Obra Dinn, designating them as clues that are central to the player’s progression in the game.

Thus, by playing the game and trying to solve the mysteries that it presents, the player is interacting with these elements buried in the game by Pope and absorbing these details. As we play the game, we learn about the specific roles of the crew on board the Obra Dinn and the nature of their jobs, we examine the detailed structure of a 19th century vessel operating under the British East India Company, and we observe events such as an execution of a criminal on the ship, an attempted desertion of the ship, and a mutiny. All for the purpose of completing the game, for achieving our central purpose as the player interacting with the game. After Return of the Obra Dinn, I realized that I suddenly understood all the terms such as “second mate,” “bosun,” or “topman,” all of which I have heard in other forms of media that include depictions of similar Victorian-era naval voyages but never enforced their narrative so effectively on me.

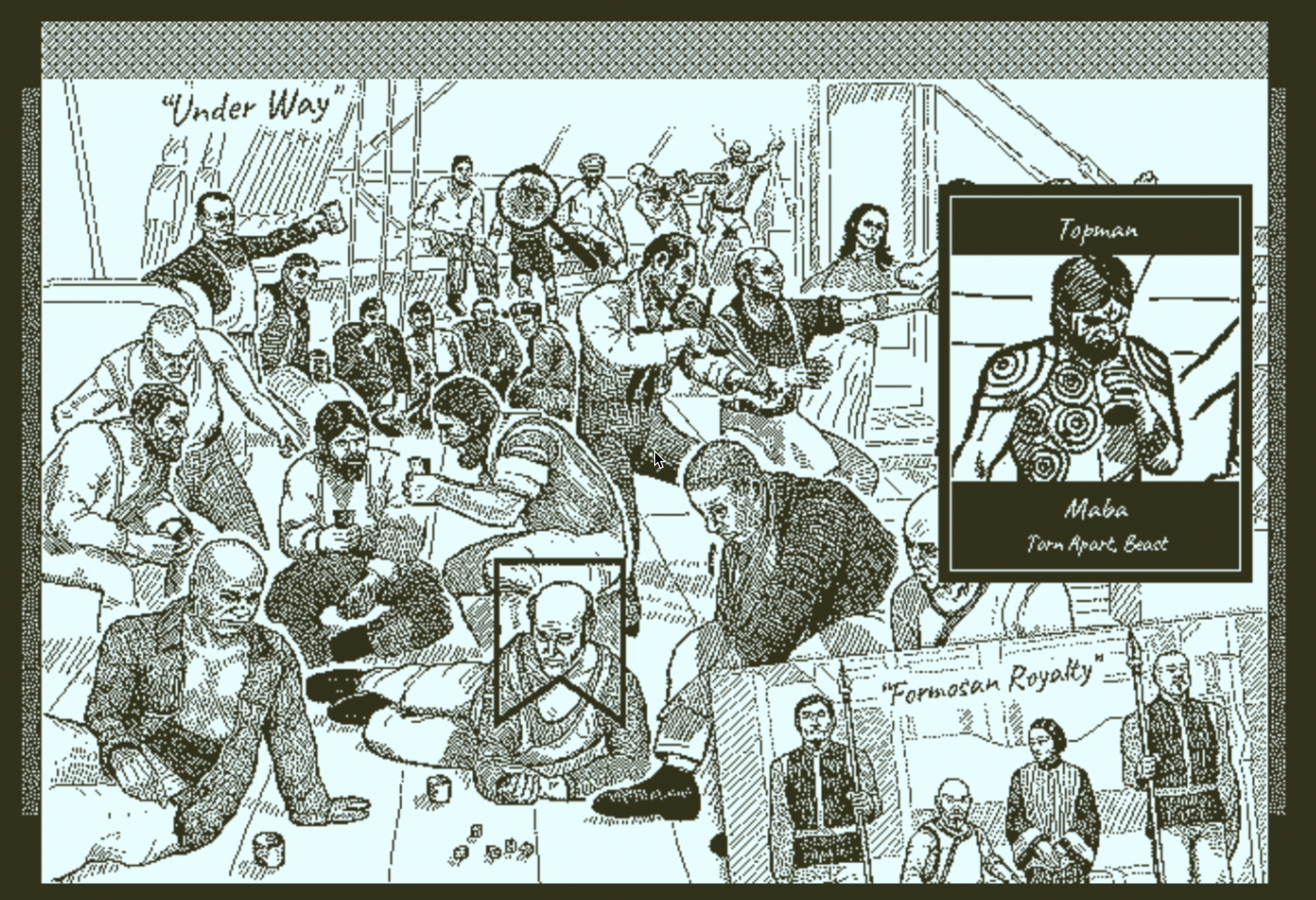

On the other hand, what is more impressive for me is how Return of the Obra Dinn reflects subjectivity of the designer in presenting its historical narrative through its mechanics, thereby truly making it a piece of historiography, a selective process of constructing historical narrative. In the core mechanic of solving the fates of the crew of Obra Dinn, what kinds of details the player should pay attention to plays a big role in this kind of narrative. Before the player is able to figure out enough names, a central part of my play-through (and from what I gathered from discussions of the game on the internet) was looking at the uniforms that each person wears during their voyage and determining their class on the ship. Almost from the very beginning, each unknown soul I encountered immediately became “unknown officers,” “unknown topmen,” “unknown stewards,” and “unknown seamen” on my notebook, classified according to their status.

Thus, the game is able to construct a narrative of the importance of social hierarchy on a 19th-century British naval vessel by using its mechanics to channel the player’s attention on classifying the crew into different social classes and entrenching this classification in their mind. During my own play experience, it was also noteworthy that Lucas Pope made determining the fates of the majority of the seamen and some of the topmen much more difficult than solving the fates of the officers and the higher-ranked members of the ship, and thus directed a lot of my end-game frustration to the difficulty of determining the identities of the lower-ranked seamen who lost their lives or disappeared on the high seas. I wonder if this is a part of the historical narrative that Pope intends to construct as well through this game, but it is nonetheless impressive that games are able to achieve this kind of historical narrative simply through its mechanics.

As a history major myself, I really like how you connected Pope’s game to historiography! Your discussion of the relationship between mechanics and the construction of a historical narrative was really interesting. I hadn’t really thought about how the game teaches the player historical concepts so casually, by introducing tools such as the glossary and requiring the player to refer to it in order to solve the mystery. Also, your point about using certain uniforms to determine class/role on the ship is very interesting – I found it hard to do that at first because of the black & white, blurry nature of the art, but I found myself relying more and more on visual clues such as that as I got more used to the game and its art.

I agree the way that the game is designed to make you focus on the clothes and titles of the people on the Obra Dinn is so interesting. I know I’ve read the words topman and second mate in books, but they never stuck until I played it. It makes me feel like I have more of an understanding of how boats work, and now if somebody threw those words out I’d understand. Even though there is a dialogue in the game to help you figure out who is who, the game is primarily visual. The dialogue is mostly useful when you’re beginning the game and gathering the big picture. I think the amount of detail the Pope put into the game’s visuals is absolutely incredible.

It’s also a very interesting way of organizing the massive roster that the Obra Dinn had at its outset, and thus the massive number of casualties that the player character has to wade through to find out what happened. I think it makes it all easier to remember; if everyone who wasn’t the captain was referred to as merely a sailor, I imagine that would make it significantly more annoying to sift through.