At the beginning of my playthrough of “Gone Home”, I was apprehensive. The premise constructed at the beginning of “Gone Home”, a young woman arrives at an empty, haunted house with no knowledge of its interior or potential inhabitants, signaled to me I was getting into a classic horror story I’d seen in movies such as Halloween or Alien. As someone who is not partial to the familiar bodily horror and jumpscares of the horror genre, I was worried that I’d be subjected to 2-3 hours of me uncomfortably squirming through a game in which I’d have to carefully tread to protect my in-game avatar from bodily threats.

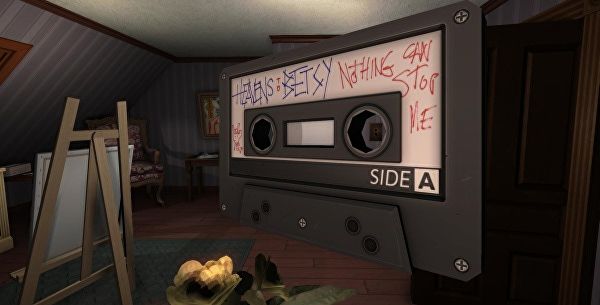

So I was pleasantly surprised to discover by the end of the game that my expectations had been completely upended: I had played through a game detailing the story of a high school girl, Samantha Greenbriar, and the growth of her romantic relationship with Lonnie, a friend she had made at her new school. It had also offered me a variety of subplots involving other members of the Greenbriar family, without even having physically met any other character. The game that I had initially to be a cliched horror game had turned into an engaging, interactive narrative right before my eyes.

Horror games have a habit of playing into the fear of their players, which keeps their players on their toes, and readys them for any potential dangers lying ahead in hard to see places or in unknown areas. As stated in the article “Coming to Play at Frightening Yourself: Welcome to the World of Horror Video Games”: “In playing the game we are required to be inquisitive, in so far as there might be a key, an item or a door where the odd sound is emanating from” (Para. 6). The inquisitive nature of the protagonist within horror games is used to the advantage of “Gone Home”, as the player is more inclined to pay greater detail to the various objects which relay the game’s various embedded narratives.

According to Henry Jenkins in “Game Design as Narrative Architecture”, stories with embedded narratives can be viewed less as a chronological series of events and more as “a body of information” where “a game designer can somewhat control the narrational process by distributing the information across the game space”. Effectively, in games with this type of narrative, the space in which the player progresses through the game is also crucial in relaying its story. While “Gone Home” has narrated segments corresponding to the journal that the protagonist finds at the end of the game, the majority of the game’s story is told through the various objects strewn throughout the Greenbriars’ spooky, disheveled house. By presenting the house as scary and undiscovered, the game designers of “Gone Home” give its players a reason to look at these story-centric objects outside of their material usefulness in progress through the game.

As someone who really subscribes to the “Show and don’t tell” mantra in regards to storytelling when reading and watching stories unfold before me, I was taken aback by how “Gone Home” had practically tricked me into investing myself into its main narrative. I’ve seen in shows how details relating to a character’s action, or the setting itself can give crucial hints to how a story’s unfolding or where a character stands. I’ve also seen objects used as Mcguffins to progress the plot, and objects used as the center of attention in detective or mystery stories. But the interactive nature of the “Gone Home” got me thinking about how games can use its setting and the various objects its placed within it to convey a story in a unique and engaging way.

MLA Bibliography

Gone Home. Windows PC version, The Fullbright Company, 2013

Jenkins, Henry. “GAME DESIGN AS NARRATIVE ARCHITECTURE.” Henry Jenkins Blog, MIT, https://web.mit.edu/~21fms/People/henry3/games&narrative.html.

Perron, Bernard. “Coming to Play at Frightening Yourself: Welcome to the World of Horror Video Games.” Aesthetics of Play: Online Proceedings, The University of Bergen, 14 Oct. 2005, https://www.aestheticsofplay.org/perron.php.

Cover Photo is from: https://www.deviantart.com/fortheloveofpizza/art/Gone-Home-Kiss-417796613