For my retrogame review, I played Asmik Ace Entertainment’s bizarre 1998 exploration game LSD: Dream Emulator (here on abbreviated as LSD) on a PlayStation simulator for Windows 10. LSD is a first person exploration game divided into 365 “days”. Each day, the player is dropped into a surreal dream world for ten minutes, during which the player is left to explore the landscape. There are a limited number of possible locations the player might get dropped into, including a village, a port, and a shrine, but by contacting certain objects in the game, the player can teleport into another location. Besides exploration, there are no other gameplay or narrative elements at all — which would lead many to qualify it as perhaps an interactive artwork instead of a game. We will return to this point later.

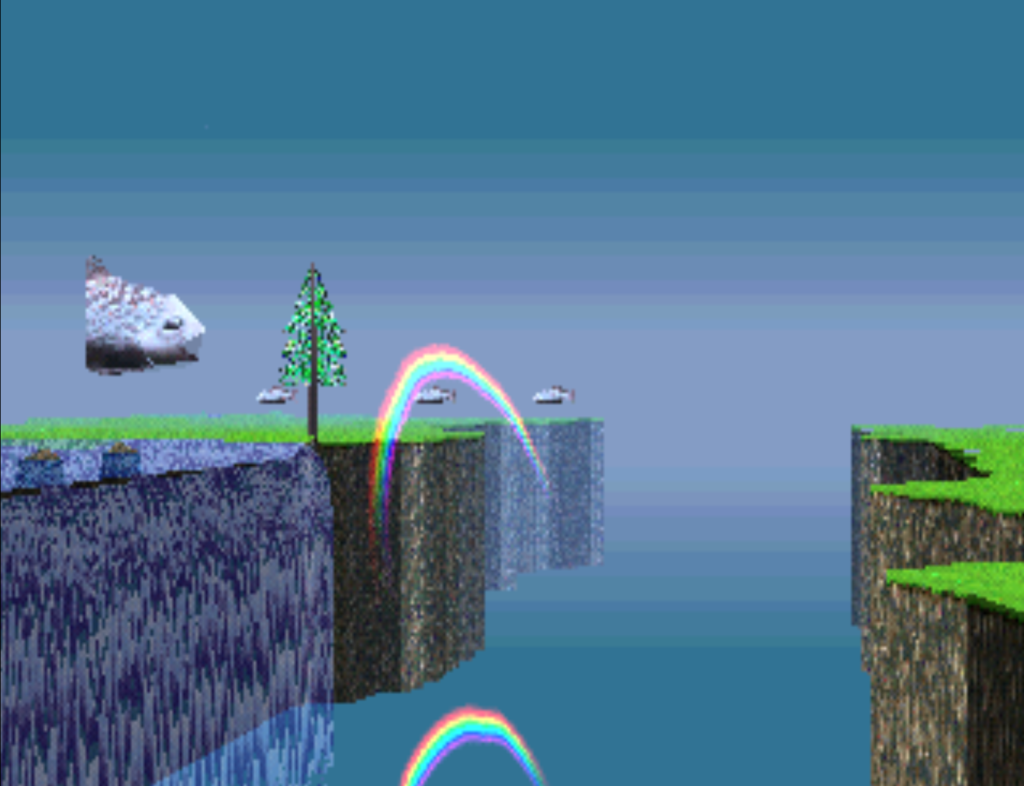

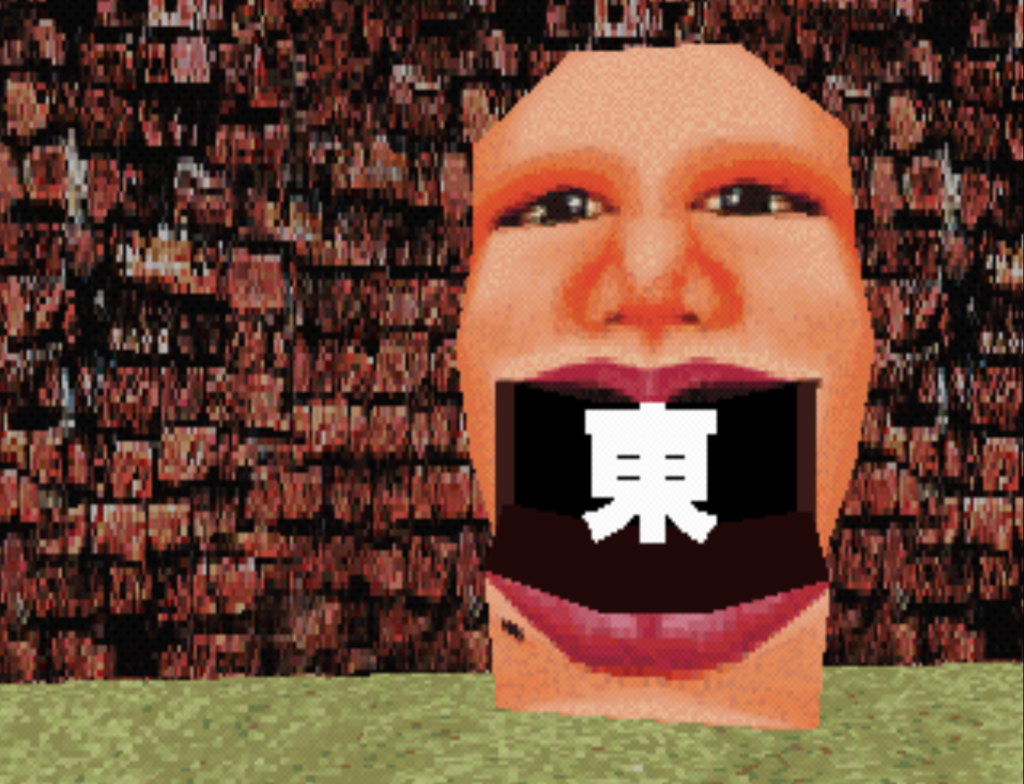

The locations of LSD are populated with grotesque and quirkish objects though the general structure of the scene remains rational and seem to follow physical rules, and each location carries with it a distinct soundtrack of electronic experimental music. As the player go through more and more dreams (days), the texture and color arrangements of the objects in these locations change more frequently and unpredictably, making the game increasingly psychedelic as we approach the end of the game.

Now, I’ll first tackle the elephant in the room: can LSD even be considered a game? Just like how many disregarded games like Gone Home as “walking-sims” when it first came out, LSD is even more radical in that it does not even have a narrative, which makes it feel more like a piece of interactive modern art rather than a game. In fact, the lead designer Osamu Sato himself did not consider it a game, saying in an interview that he rejected the idea of games but wanted to use the PlayStation as a medium to make art. However, I would argue that LSD still carries with it distinctively ludic elements. The French sociologist Roger Caillois identified four essential categories of play: competition (agon), chance (alea), role-playing (mimesis), and vertigo (illnx), and it is precisely the last element of vertigo that LSD relies on to deliver its unique pleasure (Jagoda and Sparrow, Lecture). Vertigo refers to the sort of ecstasy that comes from a sense of freedom and disorientation often manifested in children’s play of kites and spinning wheels. In LSD, it is exactly this feeling of active exploration and the bizarre visual pleasure that accompanies it is what makes the piece so appealing.

As noted by Tanine Allison in her discussion of Until Dawn, the importance of non-interactive, sensory pleasure has often been downplayed in the contemporary analysis of games (Allison, 275). With its surrealistic land-and-soundscape, LSD not only directs our attention to the sensory, but also challenges the smooth, harmless, and coherent sensory scheme of realism that dominates most games. As Boluk and Lemieux points out in Metagaming, “photorealism in contemporary videogames requires complicity on the part of the player in their own sensory and cognitive deception” (Boluk and Lemieux, 130). Whereas glitches and imperfections would be catastrophic to most contemporary 3D games, in LSD the lack of polished 3D models and rough edges in the game objects actually turns around and adds to the uncanniness and eeriness of the environment.

Drawing from Boluk and Lemieux again, “Videogames…are built upon mechanical, electrical, and computational process that inform, yet operate outside human experience” but most products choose conform to a safe, anthropomorphized visual scheme that do not challenge and entice the player into experiencing something more radical (Boluk and Lemieux, 98-99). However, surrealist works like LSD has the potential to strike a balance between the pleasurable experience of visual-ludic play and the more challenging, experimental experience of visual irrationality. The step-by-step design of LSD in which psychedelic effects build up only gradually is also a feature that could better invite the player into engaging with something unfamiliar. Although Boluk and Lemieux would argue for an even more radical work that forces the incomprehensibility of the computer’s non-human nature onto the player, I believe fun and pleasure need not be mutually exclusive with experimentation.

If there is one thing we draw from this absurd artifact titled LSD: Emulator published two decades ago, it should be that games need not conform to that basic photorealism coveted by most 3D developers, and that there are infinite possibilities to explore. In fact, even LSD itself is intensely limited: physical laws and conventional controls of w-a-s-d still apply, and hence the surrealism remained primarily visual and not procedural. Anyhow, there is a myriad of potential in surrealism that future developers can — and should — draw from, to create experiences that move beyond the “natural”.

Works Cited:

Allison, Tanine. “Losing Control: Until Dawn as Interactive Movie.” New Review of Film and Television Studies 18, no. 3 (2020): 275–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2020.1787303.

Boluk, Stephanie and Patrick Lemieux. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Jagoda, Patrick and Ashlyn Sparrow. Lecture, ENGL 12320: Critical Videogame Studies, October 2021.

In my early life, I had my first brush with artistic movements through the single medium I loved to interact with most – video games (more accurately, YouTube videos of games). I was introduced to symbolism through a playthrough of Silent Hill 2, for example, and, importantly, surrealism through a video of this very game, LSD Dream Emulator (initially as part of one of those Top 10 Weirdest Games of All Time videos). Reading this put me in the shoes of my child self – watching videos of this game left me entirely baffled, not only because this was my first exposure to surrealism (I was in shock that something couldn’t make immediate narrative sense) but also because of what you mentioned in your article – the fact that even its creator would consider it art, and not a game. This is an aside, but I think if Sato was asked the same question after the revolution in games-as-art discourse in the late 2000s, he wouldn’t be so quick to remove the game label from his title.

I also really liked how you tied readings and Until Dawn into your Retro Review. Non-interactive artistry has indeed been downplayed in gaming, which I think could be in part due to standard gamer aversion to it (see the mainstream backlash to Metal Gear Solid 4’s cutscenes when it was released, despite its fairly well-told story). I think this aspect of LSD Dream emulator put it far ahead of its time.

Thank you!!