The Oregon Trail was originally developed in 1971 by Don Rawitsch, Paul Dillenberger, and Bill Heinemann as a virtual supplement to the history curriculum for an eighth-grade history class in a Minnesota junior high school. Eventually, in 1975, the game was published by the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium and has since undergone several updates, versions, and iterations – as well as inspired a number of spinoffs, including the recently released The Climate Trail (2019).

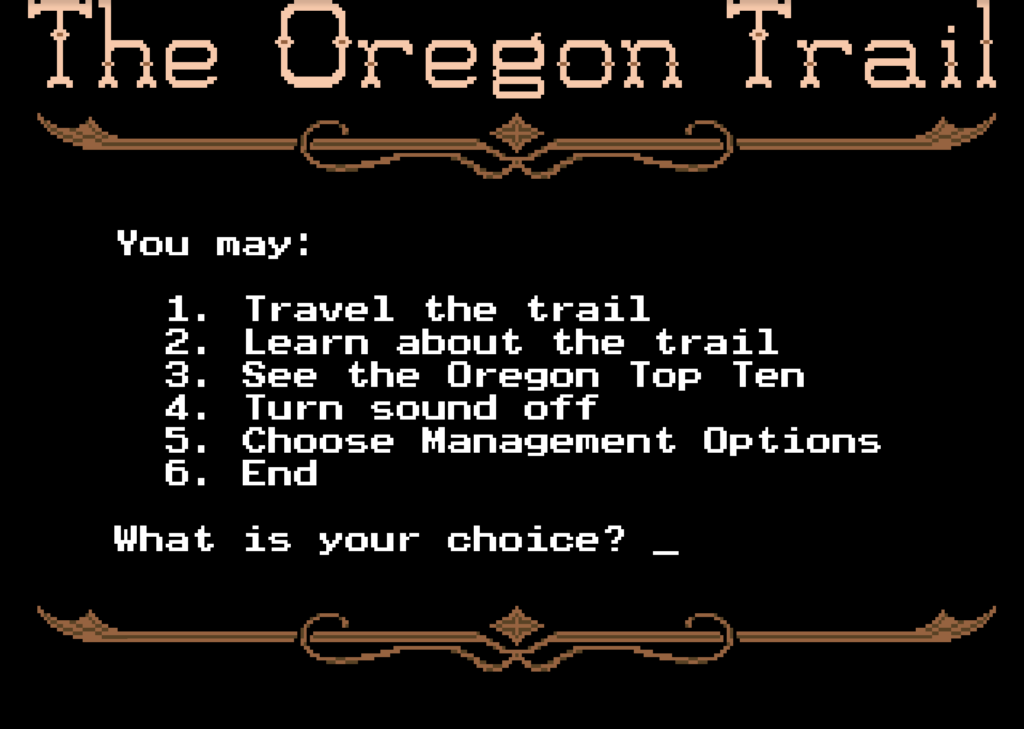

The Oregon Trail is a text-based simulator and is part educational game, part adventure game, and part strategy game. The game was intended to be a primarily pedagogical text at its inception, and the version of the game released in 1990 is certainly true to this original aim – at almost every turn, the player is able to “learn more,” whether that be by clicking the “Learn about the trail” option on the main menu page, or by interacting with fellow travelers along the way, whose pieces of advice often feel both like strategical hints and snippets of information about the places that you visit. The game certainly feels like it is trying to teach you something, but it does so without being overbearing or too overt – if you blink, you might even forget that you are playing an educational game at all. The Oregon Trail actually incorporates many of the most common elements of games from genres like strategy games and adventure games – character selection, trading, a map, and a high score.

Also, the way that The Oregon Trail doles out points feels fair and encourages replaying. The materials that you have remaining by the time you arrive in Oregon – assuming that you make it all the way there – contribute to your final score, and, depending on the profession of your character, a banker, carpenter, or farmer, your score will be multiplied by a factor of one, two, or three respectively. In this way, the game cleverly combines the player’s choice of difficulty with the player’s choice of character – rather than choosing between “easy,” “medium,” and “hard,” the player chooses between professions. This rather small detail supports the experience of a “true” simulation and engages the player in a way that makes them feel that their choice matters.

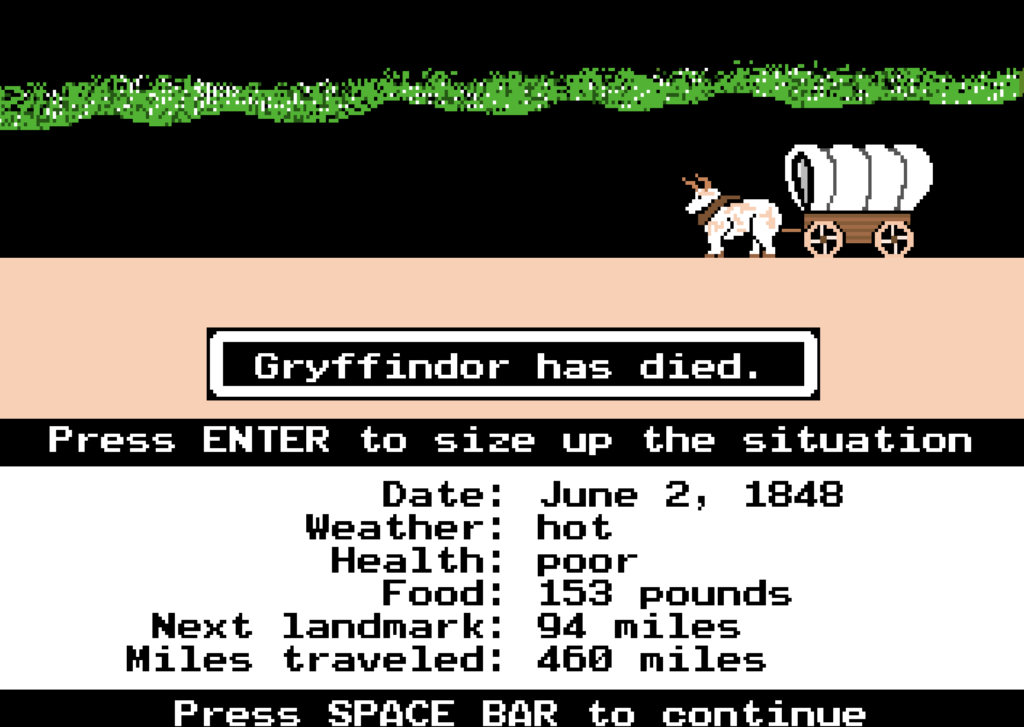

The simplicity of the game – the pixelated graphics and the bare-minimum controls – is not so much a detriment as it is endearing and even helpful. Throughout the course of the game, the player is almost always aware of the possible repercussions of their immediate actions, and navigating the actual mechanics and gameplay of The Oregon Trail is not very difficult at all. For example, when the player is faced with the choice of character, they are able to “Find out the differences between these choices,” and the player’s playthrough stats are always visible or available – the amount of food left, the number of miles to the next destination, and the status of the player’s oxen and supplies. This presentation is simple enough, and the controls are manageable and navigable enough that the occurrence of an unfortunate event, and the need to account for damages or anticipate further danger feels less overwhelming and more engaging.

Often times, the difference between a very successful trail journey and a journey that is not so successful, or perhaps even entirely unsuccessful, comes down to chance – if there is particularly bad weather or if you fall victim to thieves, the already difficult journey becomes even more so. Although sometimes the feeling that the element of chance is so significant to the probability of success can make a game more frustrating than enjoyable, it serves here rather to emphasize what seems like the main point of The Oregon Trail – that making it through successfully was difficult.

However, the historical accuracy of the game can and should be called into question, and the representation of Native Americans is disconcerting. Several times throughout the player’s journey, they will encounter non-player characters who explain that they are traveling “in fear of Indians” – although the game seems to generally resist such sentiments, it presents them often without providing context and without correcting the erroneous beliefs expressed by the characters, which is, at best, an unfortunate oversight. Furthermore, the ability to play only as the paternal figurehead of a fictional white family traveling the Oregon Trail unnecessarily limits accessibility to the narrative and does not reflect the reality experienced by many who travelled it.

Ultimately, your reception of the game will probably depend on your intention for playing it, but if you are seeking out The Oregon Trail for historical accuracy or for educational purposes, you could probably do better to look elsewhere.