Metal Gear Solid 1, developed and produced mainly by the Japanese video game designer Hideo Kojima in Konami, was released on PlayStation 1 in 1998. Even the shortest game playthrough of the game on YouTube takes about six-and-a-half hours, (yes it was played by a REALLY experienced player) presenting a complex narrative structure as well as rich game mechanics that players could explore. In the game, the player plays as Solid Snake, who is a retired US government agent sent to a nuclear disposal base located in the remote Alaskan wilderness. The mission is to investigate and ultimately cut off the terrorist threat (nuclear threat) from the former team of Snake, called FOXHOUND, a renegade special forces unit. Snake is initially unarmed when sent to the base, which determines the stealth characteristic of the game. The player has to avoid being detected by enemies as well as surveillance cameras.

First of all, I believe everyone could reach an agreement that Metal Gear Solid 1 is a fiction game. Simply because the majority of the plot has no real-life analogs. There was never any “Metal Gear” built to launch global nuclear attacks and the US government would never send only 1 person to stop the nuclear threat from a terrorist organization. (That is totally ridiculous.) In this review, however, I would like to argue that Metal Gear Solid 1 is not only a good fiction game but a successful historical fiction game. Of course, we need to first define what a historical fiction game is and what is the standard for measuring its success. Specifically, in this blog, I would like to define historical fiction games as games that are based mainly on events that have actually occurred in recorded history, added with an element of creativity where the author speculatively suggests an alternative reality. Based on this definition, a historical fiction game is successful if it manages to convince its players of this alternative reality (or this speculative future) and thus induces thoughts/reflections by raising the question “What if this really happened?” So how does MGS1 map a possible version of reality for its players?

The Historical Part of MGS1

Two big themes came out of the narrative immediately during my first 1-hour play of the game: nuclear threat and genome therapy. Let’s first talk about genome therapy. In the game, the player knows about the background of a mysterious character named Grey Fox through the dialogues between Solid Snake and the Colonel. Grey Fox is a former agent in the same unit as Snake who, after surviving severe injuries, was forcibly outfitted with a powered exoskeleton and subjected to intensive gene therapy. The gene therapy turned him into a cyber ninja with extraordinary reflex and speed. Though there was never a Grey Fox in real history, the gene therapy seemed promising at the end of the 1990s with the first approved gene therapy clinical research in the US taking place on 14 September 1990. The FDA also approved the first drug of gene therapy in 1998 which was named Vitravene. With more clinical gene therapy in use in the same age, MGS extends its imagination and optimistically (or pessimistically) speculates the future application of gene therapy.

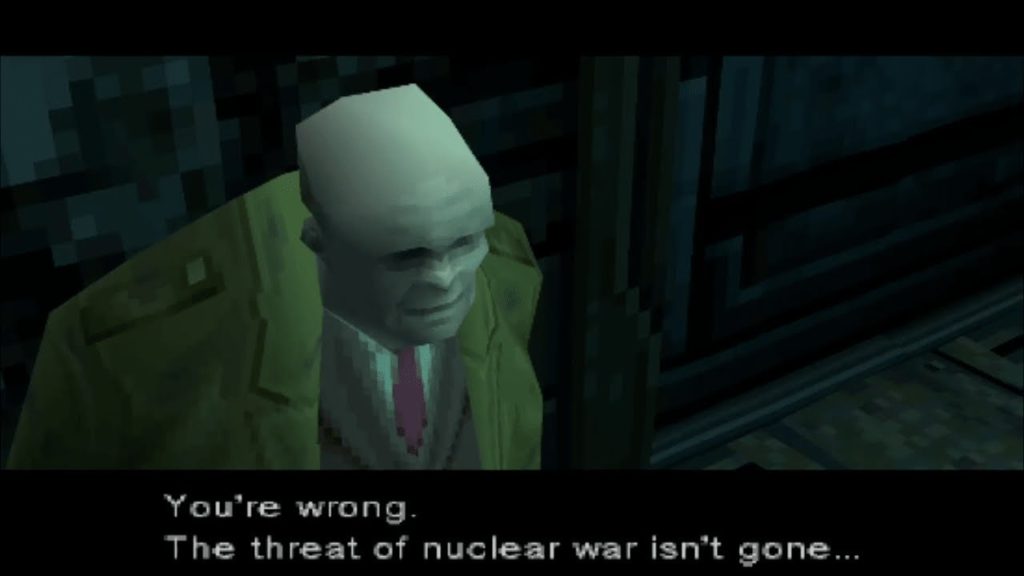

Let’s now take a look at how the game constructs itself based on nuclear-related backgrounds. Here is a piece of the script of one of the cutscenes from the game:

Solid Snake: Why Metal Gear? The nuclear age ended at the turn of the millennium.

Kenneth Baker (a fictitious president of a fictitious American defense contractor): You’re wrong. The threat of nuclear war isn’t gone–in fact, it’s greater than it’s ever been. The amount of spent nuclear fuel and plutonium is increasing even today… Furthermore, since the end of the Cold War, Russian nuclear engineers, in particular, are out of work with nowhere to turn. In other words, there’s plenty of nuclear material and scientists for making a bomb. We live in an age when any small country can have a nuclear weapons program… Complete nuclear disarmament is an impossibility. To maintain our own policy of deterrence, we need a weapon of overwhelming power.

Solid Snake: You mean Metal Gear?

Kenneth Baker: Yes… And after my company lost their bid to produce the Air Force’s next line of fighter jet, the Metal Gear system was our last ace in the hole. That’s why we pushed to have Metal Gear developed as a black project… paid for by the Pentagon’s black budget. You can avoid a lot of red tape and get a great lead time on your weapons production. And no one can bother you. Not even those bleeding-heart liberals on the military oversight committee.

As “the turn of the Millennium” suggests, the game is assumed to be situated at some point near the end of the 20th century in an alternate history, which is almost the same time as the game comes out (1998). It is based on the true historical record of the Cold War as well as the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, and most countries acceded to the treaty by the end of the 1990s. The players, who tend not to believe the possibility of nuclear war in real life, thus hold the same attitude as the protagonist Snake, who was confused and believed that “the nuclear age ended at the turn of the millennium.” It is therefore unsettling when the fictitious president Kenneth Baker reveals a fictional fact that the nuclear threat was never cleared. “The threat of nuclear war isn’t gone–in fact, it’s greater than it’s ever been.” Here we enter another fictional aspect of this game based on the true historical reality: the nuclear war might be triggered at any time, despite how countries agreed not to use any nuclear weapons on the surface. Is MGS effective in terms of convincing its players of an alternate reality? I would say Yes. The game is constructed on a fictional mission with fictional characters dealing with a fictional nuclear threat, yet the FEAR is real. The worry is real. MGS successfully invokes (at least me) the players to think about the possibility of hidden nuclear proliferation, or simply, a potential nuclear war. (Especially even in the age of 2021, the Doomsday clock is now only 100 seconds to Midnight. We are now at a distance to a global nuclear catastrophe that is unprecedented in history)

A Huge Ambition by Konami Towards Realism

While the game does well situate itself in the historical context and induce relatable tensions and emotions, its ambition towards realism further helps it convince the players that the virtual world could be “real”. It is first of all worthwhile to mention the MSG 3D engine. Compared to later games like Final Fantasies that use pre-rendered full motion videos (FMV), the MGS engine renders all of the game’s cut scenes with polygons (separately created 3D models) which used about 75% of the processing power of the PlayStation. It might be not as good-looking compared to contemporary games but its graphics were definitely outstanding and made a huge step towards realism in games.

Other details contributing to the realism in the game include 1. The footprint Snake leaves when he steps on the snow has the possibility of being detected by the enemy soldiers. 2. Snake could catch a cold outside and sneeze if the player does not enter the building quickly 3. The enemy soldiers would yarn when the player stares at them for a certain amount of time.

MGS1 as a historical fiction game maps a terrifying yet possible future for the players in 1998 and afterward. It encourages the players to imagine the alternative of nuclear warfare that could have taken place or maybe would take place. It is fun, on one hand, to see Snake sneaking into the facility and successfully rescuing the whole country from a nuclear attack on his own, and yet it is not fun to project this reality to our own and think about what if the crisis (or a similar one) really takes place.