Game Review: Grim Fandango

Skeletons, death, Día de Los Muertos, capitalism, work, Grim Fandango is an adventure game released in 1998 by LucasArts that combined these themes into a film-noir style story. In the Land of the Dead (the eighth world), the protagonist Manny Calavera, controlled by the player, was a travel agent at the Department of Death, working to escort newly dead souls from the living world to the dead world and sell travel packages to them to help them safely travel to the Land of Eternal Rest (the ninth world). In the process of escorting a good client Mercedes “Meche” Colomar, which was a commission that Manny stole from his successful co-worker Domino, Manny found the conspiracy of the department boss, who stole good clients travel packages and sold them to other unqualified clients at an exorbitant price. With the help of Glottis (his driver) and Lost Soul Alliance, an underground revolutionary organization, Manny successfully ended the conspiracy and went to the Ninth World with Meche happily.

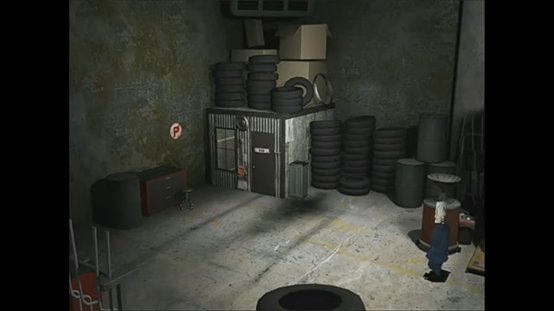

The use of filming techniques is a prominent feature of this adventure game. The environment and exploration are presented through a series of fixed camera angles, with a deliberate switch in different perspectives that manifested different scenes of the same place. The game featured almost exclusively perspectives from the environment, rather than the character’s perspective. The player never ever gets a first-person angle, but always controls Manny from a third-person view, which is manifested in diverse angles, such as high angle, low angle, extremely long shots, etc. It was rather bizarre and counterintuitive when I first played the game, as my view of the scene was so limited that I always walked Manny to corners. To some extent, it impeded the flow of the game as the camera angle switched kinda abruptly, and the puzzle-solving became more indirect as sometimes it was not entirely obvious where to go and what to get from the limited view the players had. Such features deterred the players to be fully engaged and immersed in the story, and the distance between the avatar and the player became almost emphasized here. In addition, when it came to the more intense part of the game, the game dodged player involvement by using cut scenes to finish the story, another film technique. For example, when Manny finally got to fight Domino on the boat, the game designed extremely simple moves and not-at-all intense fighting scenes, as players didn’t need to practice any skill to win the fight or risk losing their lives as they would in horror games or roguelike games. You could funnily fail to hit Domino several times with no severe consequences, and then the game would switch to a cut scene that helped you get through this crisis. Similarly, when the player needed to drag an entire huge boat from the deep ocean, the cut scene did it for you, instead of letting you ponder how to finish such an impossible task.

As we can see from the pictures, the players can almost look at Manny as if they were in front of a surveillance camera system, and Manny was the monitored subject. It is a rather strange angle and is quite different from how film techniques are used in other games, such as more contemporary games that we’ve played during class like Until Dawn. While Until Dawn used filming techniques to nurture immersion for players, as the horror film and killer perspective amplified the helpless and powerless feeling of avatars and brought them closer to players, Grim Fandango is using filming techniques in the other way around: to create distances between player and the avatar. While Until Dawn tries to immerse the players as much as possible, Grim Fandango is almost encouraging the players to sit back, feel safe, and enjoy the game from a distance, as if watching a movie. There are both pros and cons of such usage. This feature is good for telling stories and manifesting the grand background and architecture. It also translated well to a playthrough video, as a playthrough video maximizes the feeling of actually watching a film and avoiding the glitch of player control. But as a game, the player might feel a loss of control, and the distance could be discouraging or decrease the level of engagement.

Last but not least, Grim Fandango is interesting not only because it shows how the remediation of filming techniques can be used to create entirely opposite effect on players when compared with other games, but also because it can let us think about the historical flow of the game: what was the purpose of the game playing and how has it evolved? How did we move from seeking distance to seeking immersion? It can point to more future research on this topic and game’s comparison and evolvement in relation with films.

Works Cited

“Grim Fandango – Full Longplay.” YouTube, uploaded by The Adventure Gamer, 19 Aug. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcqj0APsDsM.

Wikipedia contributors. “Grim Fandango.” Wikipedia, 30 Aug. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grim_Fandango.