Introduction:

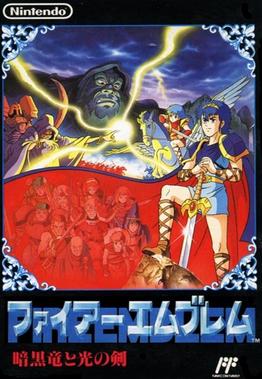

Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light is the epitome of a slow game: both in its mechanics and release. Originally released for the Nintendo Famicom system in 1990, Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light—which I will now be just denoting to “the first Fire Emblem game” hence the long title—took over thirty years to be translated for release to a world wide market. This is not to be completely unexpected, however, for its initial release to the Japanese market was met with slow sales and mixed criticism; these sales were only boosted after receiving praise from players and a Japanese Famitsu article that brought the game to a modest total of 329,087 units sold at the end of its run (Fire Emblem Wiki Source).

But why did it initially perform so poorly? The game had all the ingredients needed to be a smash hit given its development under Nintendo and the popularity of fantasy RPGs at the time. Scrutinizing the mechanics of the game, I believe that the initial lukewarm reactions were due to Fire Emblem’s key concept of taking the topic of war—a common a subject in fast, action packed video games—and translating it into a slow methodical strategy game that punishes players who want to play quickly.

Fog of War or Slog of War?

While it’s far from the truth that the first Fire Emblem game was the founder of the tactical role-playing genre, it still is arguably the most popular series to utilize this battle system and paved the way to a lot of genre staples going forward. For those unaware, tactical role-playing games are known for being turn-based strategy games in which players move their units along a grid system to attack and defend—commonly compared to being sort of like chess. However, unlike popular turn-based games at the time like Final Fantasy where you only have to worry about four controllable characters at a time, Fire Emblem has nearly fifty playable units with some maps allowing up to sixteen of those units to be deployed.

This means that you not only have to move and or attack with each of your characters each turn, but the enemy also has even more units of their own that have to go through the same exact motion. This has earned the game its infamous reputation of being slow and long winded, especially coupled with the fact that permadeath—meaning that units do not respawn after battle—is a feature that often has players restarting their consoles and redoing hour-long sections of gameplay.

Slow & Steady Keeps Your Friends Alive

The discussion on the critical theory behind slow games that served as our branching topic for week six is embedded within the core gameplay mechanics of the first Fire Emblem; I would actually go as far to say that it is a purer form of slow then something more “cozy” for the sense of urgency at each move creates a negative feedback loop for players who move too hastily. Games such as A Short Hike may have a naturally slower pace than most games, but there is no active punishment for playing fast; Fire Emblem is nearly impossible to blaze through as a first time player, you have to carefully think about both yours and your enemies’ positioning or else you could very easily place yourself in a game over state at the death your prince Marth—which to note, the game is designed that every enemy that can will exclusively target him.

Experiencing the true nature of the first Fire Emblem’s gameplay, I now have a shifted perspective on what slow truly means. A sense of urgency and pondering in moves can greatly contribute to the pace of a game, and I believe that Fire Emblem excels within this field as it has rewired my brain while playing to actively self-punish when I get to careless and quick with my decisions. A slow game is not one that just can be played at a leisurely speed, but one that has to be if you want to make it out alive.

Slow Sales Are No Longer an Option

Now sadly due to my lack of knowledge and my early withdrawal from UChicago’s Japanese 101 course, I was not able to play the original 1990s version on the Nintendo Famicom. The version I played was the Switch’s 2020 virtual limited edition release. You heard me, the game that spent thirty years getting a translation was only available from December 4th, 2020 to March 31st, 2021—just a mere three months. Perhaps a direct response to the original’s slow sales, Nintendo was planning on selling it as fast a possible with the release of a limited edition game bolstering sales exponentially within early weeks of the localization’s release: (“Fire Emblem’s 30th Anniversary Edition Is Continuing To Sell Like Hot Sweet Buns“, The Gamer). Alongside the emulated version of the full game came a range of “improvements”, one of those being an option to speed up both the player’s and computer’s turns to make them twice as fast. This was not a feature I utilized, for even when doing so it is very clear how non diegetic it is to the game. This can be seen as all the music in the game is sped up to an unnatural point, and all audio cues and animations just seem off in this feature that simply just speeds up the emulator itself. This is not only disingenuous to the real game, but also removes those key points of tension as you anxiously await to see if your unit will survive a blow at low health. While the issue of game preservation seems to be a real concern for Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon and the Blade of Light due to the western release no longer being available, it will regardless live on in new and old games alike as that slow and methodical burn lights up the minds of players everywhere.

This was a really fascinating read! I was also considering writing about old Fire Emblem’s “slow game” elements, particularly with how they relate to Genealogy. I really like how you incorporated permadeath- I think it’s a very poignant thing to talk about when considering why the older titles feel slower and more repetitive, because you likely have to play the same section multiple times. It also makes the game that much more harrowing, as every decision feels tense.

It’s interesting to consider how this slow element seems to be phased out of the newer Fire Emblem titles- I think as far back as Awakening you can skip the enemy turn, making the game much faster, and speed up your own battle animations. This is definitely good for accessibility and convenience, but I also think there’s a deeper trend when considering genre.

One could consider the difficulty and slowness of the older games to be a commentary on war itself. Battles are slow, difficult, and require an intense amount of planning and thought due to permadeath. Contrast this with the newer games, where characters have confident quotes during combat, flashy critical animations, and can do fun things off the battlefield like having tea or going to the beach. From my own personal experience, finishing a level in Three Houses or Awakening made me feel energized, ready for the next level, and accomplished. Finishing a level in Genealogy or Thracia I only felt exhausted, and relieved I had survived. The pictures of wartime painted are very different, and while the new games are indefinitely more fun and easy to recommend, I can’t help but feel there’s a significant tonal shift in the gameplay itself.

Thanks for the post! It was a very fun read.