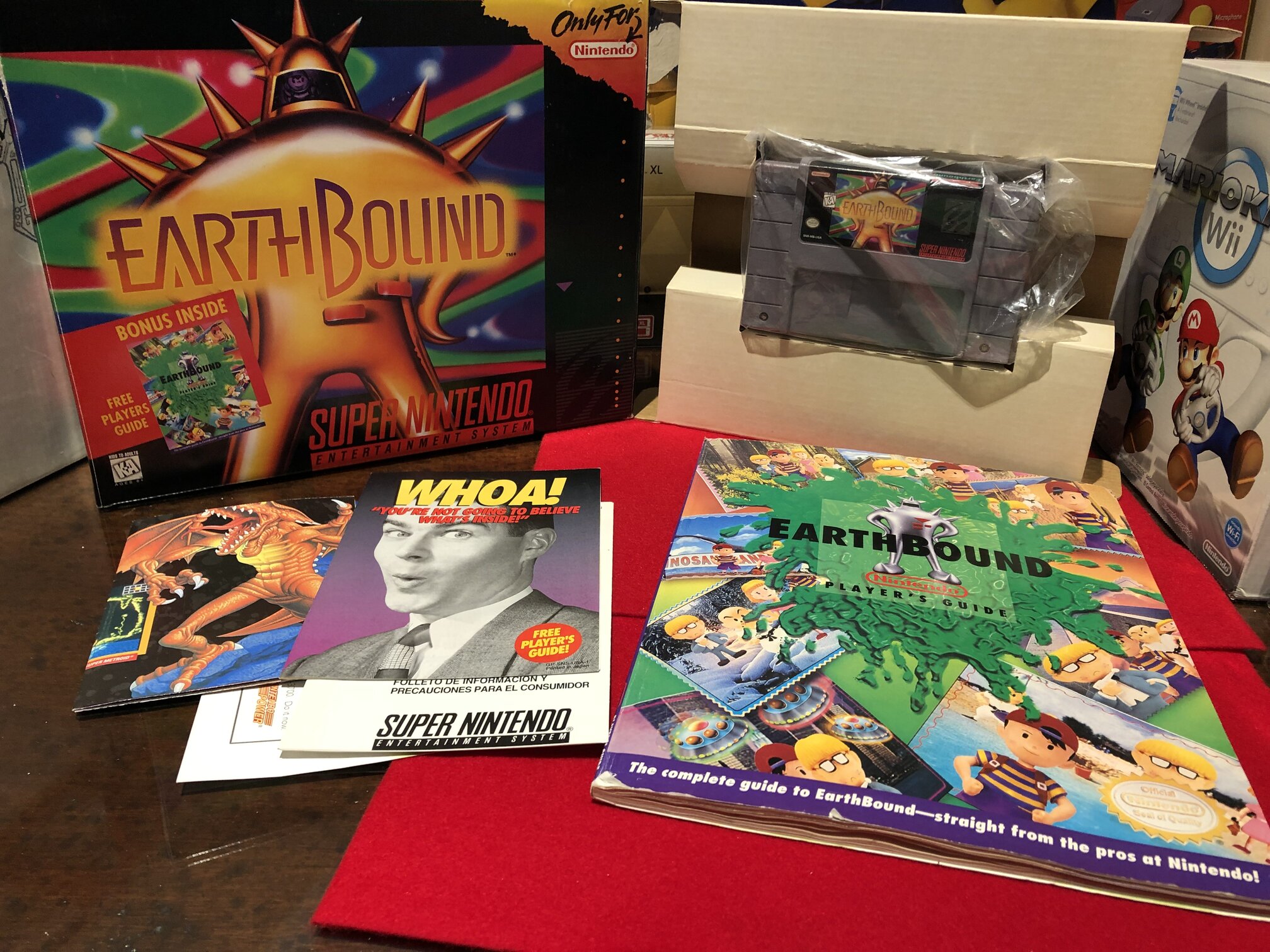

Game Review: Earthbound

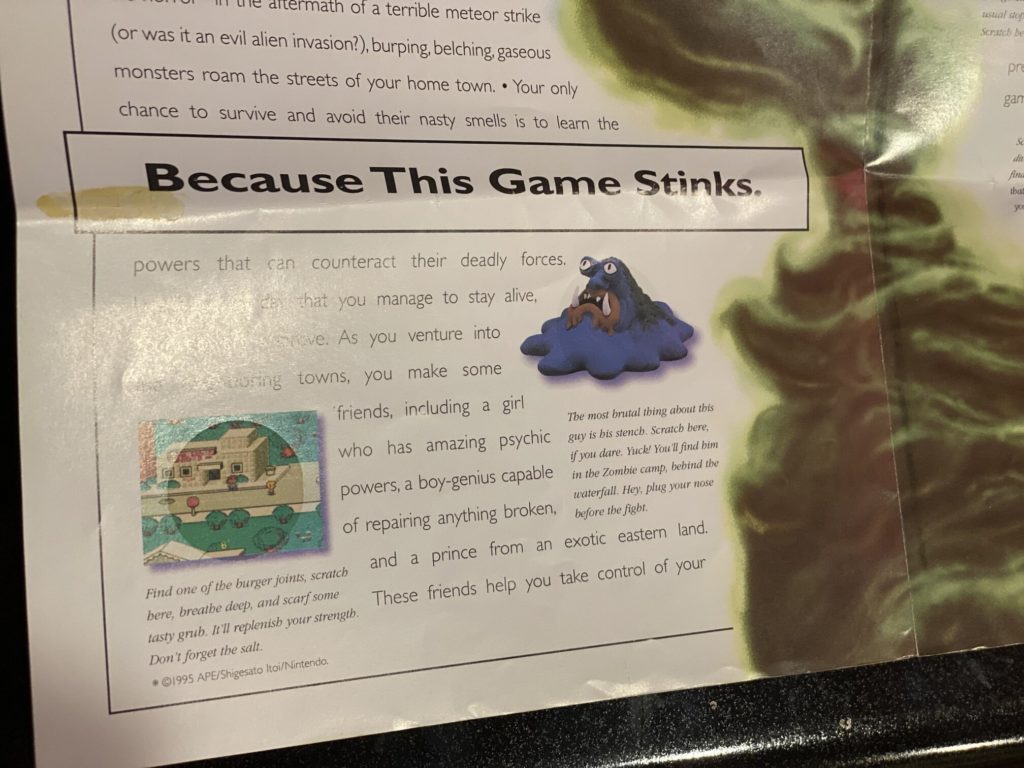

Released in June of 1995, Shigesato Itoi’s Earthbound sold only 140,000 copies upon its introduction to American audiences. When compared to other American sales figures of JRPGs for the Super Nintendo, this number is depressingly low. For example, Chrono Trigger, released earlier in 1995, sold 289,000 copies, while Super Mario RPG sold over 900,000 copies in 1996. Clearly, this wasn’t an issue of genre; while JRPGs weren’t the most popular in the US, they were still performing quite well in their respective circles. This relatively pathetic showing could, however, be attributed to its satirical advertising. Throughout 1995, the game was marketed as “stinky” and “gross,” with magazine inserts often including scratch ‘n sniff stickers with some disgusting scents.

Pictured top: An advertisement put out in Nintendo Power Issue 74

Pictured bottom: Another advertisement, though I am unaware of which magazine this came from

Despite this, it not only managed to cement itself as one of the most influential JRPGs of the 1990s, garnering a cult following that has lasted years to come, but has remained a relevant and a fantastic play, nearly 30 years later. Just how did it manage to stand out from the other emerging JRPGs at the time?

The game begins with a customization menu, allowing the player to change the names of the four main characters (and Ness’ dog), as well as contribute their favorite flavor, food, and thing. The nature of these questions and vague results set up the tone of the game that awaits, while beginning to build a connection to the main character. For example, I chose cookies as my favorite food; while I was unaware of it at the time, it set Ness’ (the main character’s) favorite food for the remainder of the adventure. While the naming of a character in Japanese RPGs has its origins in earlier examples, such as Dragon Quest, this diverse selection of other customizable options first debuted in Earthbound, setting the standard of many other JRPGs that followed. Getting to name everything from your favorite food to your special move (for which you are prompted to state your “favorite thing”) makes the player feel involved in the process of world building. Because I felt my influence in Ness and the world around him, I became more invested in his adventure.

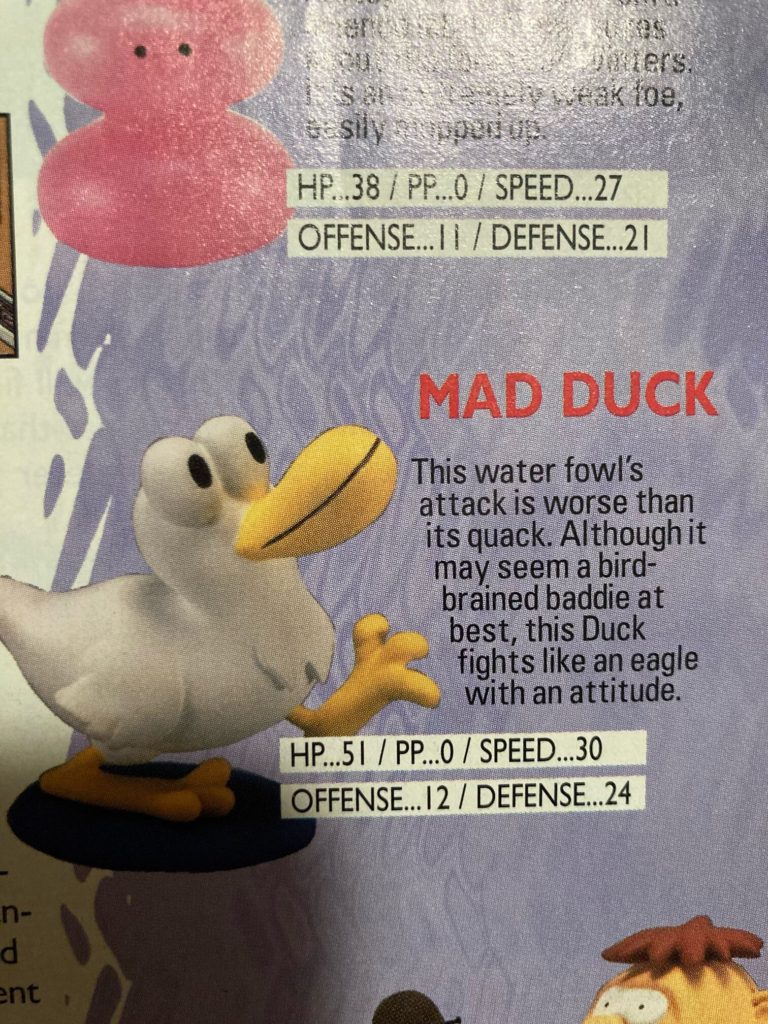

It might seem strange that a game that earns so much investment from the player could sell so poorly. The answer to this peculiarity lies in the advertising campaign that, although not effective at the time, was no doubt an honest look at an important part of Earthbound’s long-term success: its humor. Many other JRPGs coming out at the time, from Chrono Trigger to Final Fantasy III, took themselves very seriously. In fact, games in general were taking themselves seriously. Earthbound flipped this on its head. Ness has to use a Pencil Eraser to erase pencils in his way. He has to use Eraser Erasers to erase erasers. A man makes a dungeon for you to traverse, and later gets transformed into a dungeon that you enter and must complete. Enemies consist of plague rats, dinosaurs, mad ducks, circus tents, fire hydrants, manly fish, unassuming local guy, and so much more.

The lightness of these scenes and fights do a perfect job of splicing the serious aspects of the game. Many heavy topics are dealt with throughout Ness’ journey. By interjecting it with humor, I never felt like I was slogging through the story, but rather enjoying the adventure.

Mechanically, Earthbound forces the player to slow down their gameplay in many ways JRPGs try to avoid. For example, the menuing system is specifically set up to deter the player from making quick decisions. Each character has 10 inventory spaces, with the ability to swap items between them. While shopping, if the player wants to give Ness an item even though his inventory is full, they must exit the transaction, swap items with another character, and then reenter and buy it. It would’ve been simple to implement a system in which the cashier automatically buys whatever item they’re replacing. However, it seems to me that this was an intentional choice, made to force the player to think about what they’re buying and who they’re giving it to. While I understand the frustrations that this mechanic may entail, by forcing the player to take a step back and think, they have to seriously consider the gravity of their decision to buy a certain item; as money is pretty hard to come by for the first half of the game, this sets the player up to be aware of its importance throughout the story.

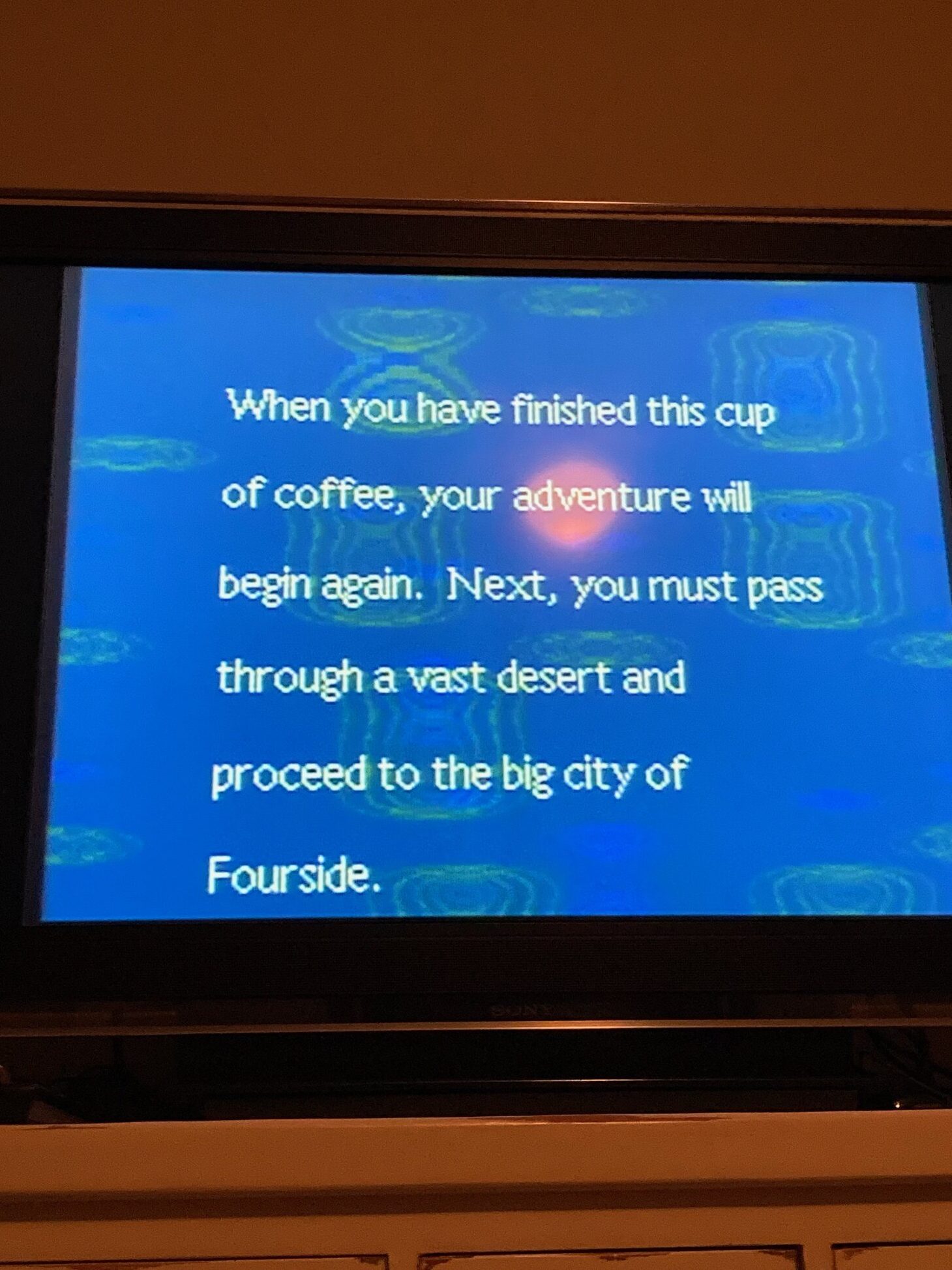

The game also continues to imbue the value of time in the narrative sense. There are several moments where gameplay is completely and utterly halted. Twice, Ness gets the option to take a coffee break. If he agrees, the game’s setting changes entirely. The background is filled with whimsical patterns and text begins to scroll on the screen, recounting your story thus far.

In many games, nearly every moment is filled with information, whether it be plot, setting, motivation, etc. Earthbound chooses to forgo all of this in moments like these. In their place, it gives the player a moment to stop and reflect, to think back on where they’ve come from and where they’re going. Doing so not only creates a contrast between the different levels of action experienced in gameplay, but also gives the player space to breathe. Earthbound is a long game; it took me nearly 40 hours to beat. Although it is filled with excitement, Itoi gives the player several minutes of quiet reflection.

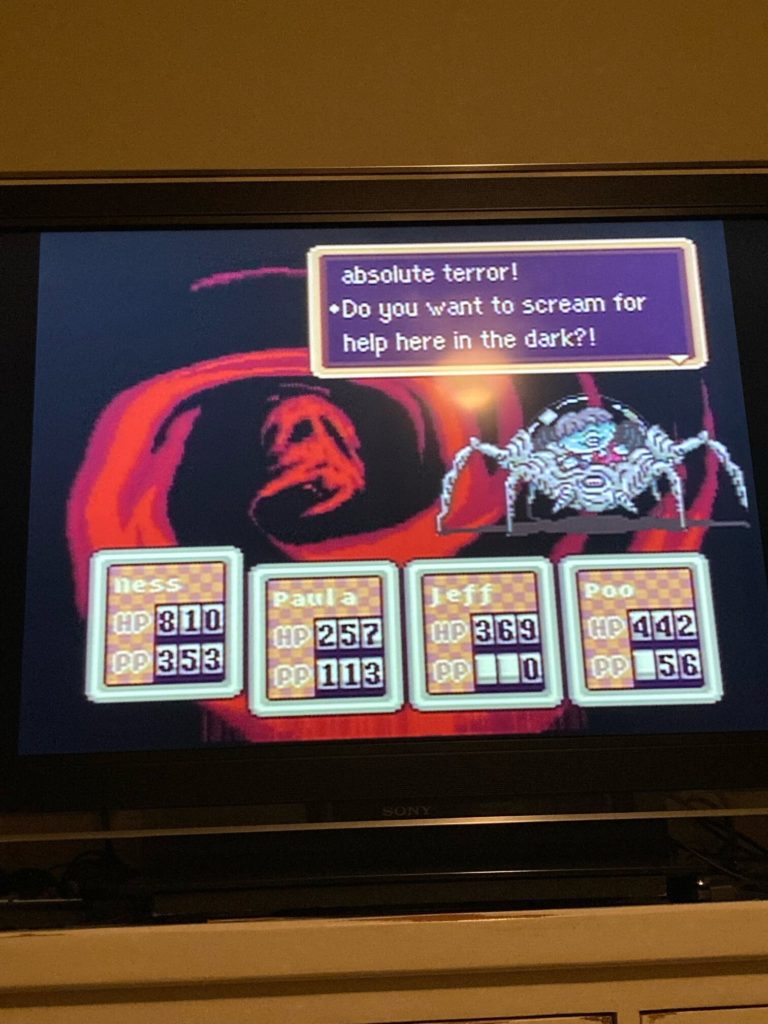

The final boss, Giygas, is presented as an abstract figure, devoid of any physical body. He oozes pure horror, embodying pure malice and a desire for destruction, but his backstory and motives are entirely unknown. Although he is mentioned frequently throughout the game, he nonetheless remains a mysterious entity even when confronted in the final battle. As such, what he represents is up for the player to determine.

In fact, the whole narrative structure of the game can be approached from many different angles. If a coming-of-age angle is used, Giygas can be interpreted as the inner fears of Ness personified, its defeat only possible with the help of friendship. On the other hand, if the player chooses a more literal approach, they can see Giygas as an interdimensional alien, doing its best to spread chaos no matter the cost. Even a couple months after beating the game, I have continued to think about what the story represents. This greatly increases the replay value Earthbound holds; on every playthrough, something different can be gleaned each and every time.

Earthbound is one of the most influential games I have ever played. I often play games from the SNES to N64 era, and although many have impacted the sphere of game design greatly, upon revisiting certain titles, they seem clunky and outdated. Earthbound feels timeless. Its humor remains relevant, its mechanics still seem fresh, the story is beautifully written, and the world made me feel everything from terror to love. I cannot recommend this game enough.