The other day, I came across a Twitter trend: “Metroidvania”. The tweets attached to this trend were centered around the question of if the recently released Metroid Dread was a metroidvania or not. The debate was heated, so much so that the instigating tweet has since been deleted.

Metroidvania, for the uninitiated, is a genre term for a videogame which is similar to its namesakes: Metroid and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. Alternate terms have been proposed, such as “search-action games”, but metroidvania is the one that has stuck. These games have seen a resurgence in recent years, with popular indie releases like Hollow Knight and Ori and the Blind Forest, and even some larger releases like Metroid Dread. Despite this popularity, there still isn’t agreement on what metroidvania means, with some definitions as specific as “a Castlevania that plays like Metroid”. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is the first of the Castlevanias which has a similar game structure to Metroid, and thus by some definitions it is the first metroidvania. It was already on my radar for this reason, but this online discourse made me all the more interested in playing the game. Not only was Castlevania: Symphony of the Night an interesting look into the history of this ill-defined genre, it was an engaging and exciting experience that I can’t wait to return to.

Earlier I mentioned that Castlevania: Symphony of the Night is a Castlevania game which plays like Metroid, meaning that is that the game is a 2D platformer with a focus on exploration. You play as Alucard, the son of Dracula, returning to Castle Dracula to discover why it has returned. The castle is crawling with enemies for Alucard to battle with the variety of weapons you collect, from swords, to maces, to nunchucks. As you explore the castle, you gain new abilities which allow you to unlock now areas of the castle. These new abilities will eventually lead to even more new abilities; this is the loop of Symphony of the Night.

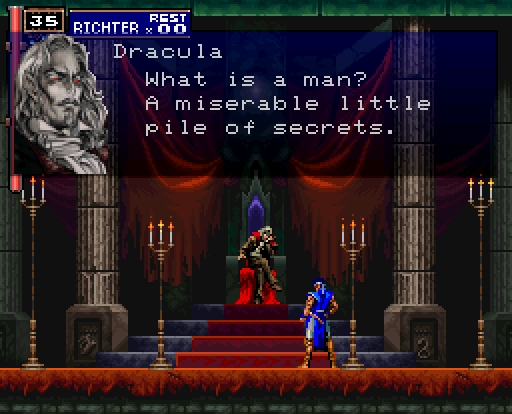

If there’s one word which best distills the Symphony of the Night experience, it’s “cool”. I know that’s an easy thing to say about a lot of games, but I found it to be especially true of this game. The first and perhaps most obvious example of the game’s coolness are its visuals. Castle Dracula is filled with visually stunning rooms and incredible spritework. I’m a particularly big fan of the impressive stained glass and paintings which adorn the castle walls. The game is 2D, releasing in an era where 3D was the expectation for all new releases. It looks none the worse for it, and the team clearly put their all in. Some of the boss designs alone were jaw dropping. Animations are smooth and easy to understand, making fast-paced combat situations simple to navigate. There was never a moment in Symphony of the Night where I didn’t understand what was happening visually, even when there were upwards of ten enemies on the screen. Music is similarly high-quality; very synth-heavy with lots of electric guitar to back it up. The story of the game leans heavily into traditional gothic horror tropes, delivered through fully-voiced dialogue boxes. The voice acting is admittedly corny, but it’s hard not to buy into the delivery of some of these lines.

Next on the list of cool things are the combat and movement. Alucard only starts with one power besides jumping and attacking: the back dash. By pressing triangle, Alucard will slide back about a sword’s length away from the enemy. You can continually press this button to dash quickly along the ground, and you better believe I back dashed around almost the entire game. When Alucard moves, he’ll sometimes leave behind a blue shadow, an effect which is especially cool when he’s sliding along the ground. Jumping is snappy and only gets more fun with the jump upgrades you get as you explore, a higher jump and a double jump. Combat rewards patience, waiting for an enemy to attack then striking between their movements. Of course, Alucard’s movement plays an important role in this rhythm – using the back dash to quickly disengage, jumping over projectiles, and ducking below swings. Weapons have varying damage, range, and attack speed, a small set of parameters which change your combat style drastically. It’s rewarding to learn to adjust to a new weapon and do well with it.

Castle Dracula is an endlessly engaging environment, flowing from ancient libraries to rainy ramparts to majestic cathedrals. Its rooms are arranged in an easily-understood loop, lending itself well to exploration gameplay which has you returning to areas multiple times. The castle is a model for explorative environments in this way. Some individual rooms are harder to navigate than others due to unintuitive layouts, but it was overall a joy to explore, then re-explore in the late game upside-down version of the castle.

The game falters a bit in some areas, as all games do. I believe a lot of this can be attributed to its age. Death is common in Symphony of the Night, but after death you aren’t booted to your last save; you have to first return to the title screen. Loading times between areas are also non-trivial, partially due to the early-CD technology the game is based on. These are small complaints, friction left over from the era the game was released but they take away just a bit from a game which is otherwise excellent.

It was hard not to think about the other games in this genre-lineage that I’ve played while playing Symphony of the Night, since they so clearly called back to this game’s structure and design, even down to enemy patterns (I noticed one boss, Olrox, shared some attacks with the titular boss fight from Hollow Knight). One of the most prominent things descended from this game was its way of doing multiple endings, which I’ve seen replicated in both Cave Story and Hollow Knight. You can play through the game up to the final boss and get the credits, however, there exists another ending beyond that first ending which you can unlock by completing the final boss with an item found by exploring. It’s a method of unlock which is specific to this genre centered around exploration, and it’s interesting to see where that trope originated.

Whether you choose to call this genre metroidvania, search-action, or something else, it’s hard to deny it owes its history to Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, and after playing it for myself, it’s easy to see why. The game is a perfect blend of exploration and action. You probably noticed that I keep writing lists of things to find in the game in this review; that’s because Symphony of the Night provides incredible variety for its relatively short playtime, nearly all of it high-quality. It’s exactly the type of game you’d expect game designers to want to emulate. Whether you’re a fan of metroidvanias or checking out the genre for the first time, I fully recommend Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.