Released in 1980 and designed for Atari 2600, 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe is a twist on traditional Tic-Tac-Toe through its addition of dimension. Whereas in traditional Tic-Tac-Toe, players win by connecting three of their symbols in a single plane, 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe, by its design, enables the players many more ways to win: connect four on a single plane, and connect four across different planes. Through simple interaction with the joystick controller, symbols representing the players hover across the planes, and settle down when players press the button “A”. Resetting the game through the reset controller on the console would render a new game, while the select controller on the console can be used to choose between different difficulty levels.

The level design of the game is, like its mechanics, easy to comprehend. The game offers Level 1 to Level 9. At Levels 1 to 8, the players play on their own against an alleged artificial intelligence. The rise in difficulty is correspondent to the increment in the number of future steps that the AI is going to ponder when making a decision, which can take a very long time, sometimes as long as several minutes. At Level 8, I have personally experienced a wait time of five minutes, to the point where I questioned whether the laptop on which I was running the simulator was broken. The last level, Level 9, is a two-player level. That is, the player can invite a human friend to play together at this level.

This level design becomes intriguing when one incorporates a number of elements of the game to decipher what the game really is about.

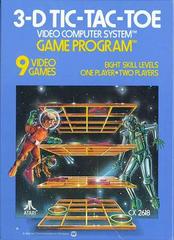

The cover of the game offers some first-hand hints. On the left, we can see a boy in an astronaut suit, floating in the backdrop of what seems like outer space. On the right, we see what seems like a robot, or what presumably is hinting at artificial intelligence. In the middle is an illustration of the 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe, and it looks like the boy is playing against the robot. With the saturation of these sci-fi elements, this cover really demonstrates an innate fascination–the fascination of a futuristic vision, narrated by our fictional works, our culture and society as a whole. It is as a spectacle, ever charming and ever evocative to the late 20th century human.

The conception of playing against an artificial intelligence, as represented by the cover of the game, is also forcefully evident in the gameplay experience itself. Again, switching between Levels 1 to 8 would render a difficulty level that’s correspondent to the number of moves that the AI will ponder when thinking ahead. Embedded in this level design is a set of rules for execution, dictated by the computer program and the codes that it entails. At Level 1, what is allowed to be executed by the artificial intelligence is to think one step ahead, which renders a quick response of a few seconds. It is not allowed to think more ahead than that. At Level 8, however, the AI is obliged to execute the 9-step-ahead forward thinking, assigned to it as an unbreakable rule by the program. The AI, which represents the computer program and executes its procedures at each level, is no more than what Ian Bogost would call a procedural representation of the game’s intrinsic programming. As such, the AI that strictly follows the game’s rules and procedures, is in fact not “AI” as in a truly intelligent being. Its function, rather, is more like a character, or avatar, of the game. This invisible being that the player is imaginatively and conceptually playing against, is essentially a medium through which the game gains expressive capacity towards the player, who associates the procedural representations of the game with larger cultural and societal preexisting archetypes and conceptions of artificial intelligence to conjure up this figure of “artificial intelligence” within the game, ultimately creating meaning in what is originally a lonely and tedious one-player Tic-Tac-Toe game. That is, the players play against what is merely a phantom–a representation of the game’s procedures–for the whole duration of the gameplay experience, while this phantom indeed lies solely in the imaginative and interpretive faculties of the human mind.

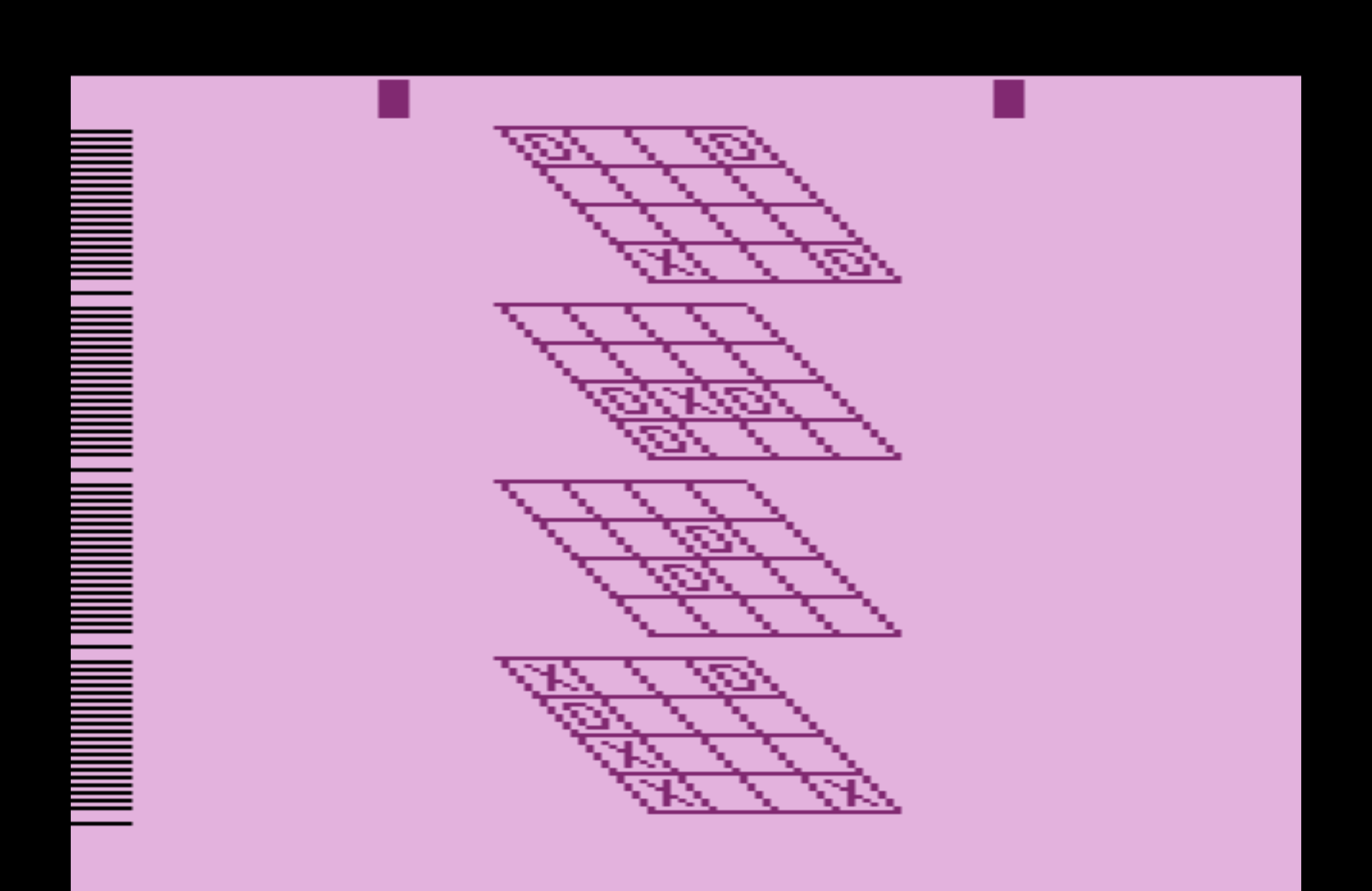

The game also irritatingly interrupts the flow of the gameplay experience with constant reminders/reinforcements that the player is playing against an “AI.” This is achieved through the prolonged wait time at each higher difficulty level, where the “AI” is processing more steps. On screen, the visual that represents this “thinking process” for the “AI,” is a series of inserts of colors that covers the whole screen and flashes randomly. This visual intrudes the cohesive gameplay and enforces the overarching conception of artificial intelligence in the mind of the player. This kind of intrusiveness is also observable in the sound effects of the game: a repetitive shock-wave noise that resembles a mechanic alarm. Together, the visual and the sound enable capacities for value judgement through the evocation of emotional responses in the human player. That is, the visuals and sounds create a sense of eeriness and panic in the player, who then is led to antagonize the game–the imagined “AI,” in the belief that the “AI” is truly capable of intelligence compatible with that of human’s, and that the “AI” is meticulously hostile against the player.

On the contrary, Level 9 of the game–two human players–offers the player a matching human intelligence, which the player feels relatively at ease with, for it can be attributed to a real physical person. The alertness that’s embedded in Levels 1 to 8, in which players are playing against the “AI,” is in distinct contrast to the relative relaxedness of Level 9. The intrusive visuals don’t reoccur anymore, and the player can observe a thinking process similar to their own: the screen doesn’t just flash when the other human player is pondering what step to take, instead, you can see clearly how the other player think for they use the same mechanic as you–they control their symbol such that it hovers on the screen. This continuity and visibleness of the human player strikingly contrasts with the intrusiveness, secretiveness, and invisibleness of the “AI” counterpart, such that the game expresses not just the idea that the human intelligence is higher than the “artificial intelligence” (through setting Level 9 as the highest level), but also the idea that the human intelligence is familiar and friendly even in a competitive setting, whilst the “AI” is a vast unknown hostilely confronting the player–or straight up terror.

In all, 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe is not merely 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe. It is a game that attracts players with the futuristic sci-fi spectacle, and then expresses embedded ideas about artificial intelligence and human intelligence through the gameplay, in which procedural representations and rhetorics conjure in the human player’s mind the opponent of an “artificial intelligence.” As such, this seemingly simple game drives players to confront with and reflect upon their fears of artificial intelligence, and also scrutinizes our cultural conception of artificial intelligence.

Again, 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe is not merely 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe. It is also a mirror reflecting the late 20th century human society–its reality, its infatuation, and its phobia, all converging to form a human psyche that awaits and anticipates at the dusk of the century and the dawn of the new. This game is a masterpiece precisely in this way.

I love your analysis! The way 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe presents its procedurally generated opponent as an AI, at its heart a procedural and algorithmic program despite various cultural connotations, reminds me of how most games anthropomorphize their procedurally generated opponents. Although game developers refer to enemy algorithms as enemy AI, game players receive their enemies in anthropomorphic forms (and more broadly animalized or bestialized forms), essentially representing the algorithms as what they are not according to common belief, life forms; whereas, mazes, dungeons, puzzles, and other ambient elements of a game are commonly received as procedural and algorithmic.