Fire Emblem: Genealogy of the Holy War is undoubtedly one of the more obscure titles getting a retro review for this class. It already belongs to a niche genre, strategy role-playing games, and the game itself was never released outside of Japan – for non-Japanese audiences, it is only playable through translations in an emulator. Yet, even so, this odd SNES game with a pretentious name has persisted- fans of its series, Fire Emblem, regularly recommend this title regardless, and I first chose to play it in 2020, 24 years later. So now, during its 25th anniversary, I dive into the question you all must be wondering: why is Genealogy so revered? Is it worth playing today?

Genealogy is a fascinating title for fans of strategy role-playing games or the Fire Emblem series as a whole. It was a landmark entry for the series, and the birth of many iconic features, such as the weapons triangle, a home base, support conversations and pairings, and special skills. It also serves as a direct story inspiration for many of the most recent titles, most notably Awakening and Three Houses. Yet, this is a niche recommendation- one I have made for fellow fans in this class, but not a reason why general audiences might appreciate this game. Why, then, is Genealogy, a niche game from 1996 and one of the few Fire Emblem games never translated, relevant to the video game landscape as a whole?

Genealogy’s most famous feature is its lengthy and complicated narrative, spanning the promised genealogical lines to tell a story that spans over generations. At its most simple, however, it is the story of two families, deeply intertwined in conflict. Sigurd, the main character of Genealogy, is the classic fool with a heart of gold- beginning the story by calling upon his friends from military school to help him resolve a conflict in a nearby country, and accidentally falling in over his head. The other main character introduced in the first chapter, Arvis, is quite the opposite: a schemer after a difficult childhood and the duplicitous reality of court life, yet sympathetic- he wishes only to alleviate the ills of the world that made his life so difficult, but needs the power to achieve that. This is already a unique story for Fire Emblem to tell- the main character is an adult, with a more complex personal situation and political background than an evil emperor to overthrow and reclaim land from.

Arvis helpfully gives Sigurd a valuable weapon in the first level

The protagonist, Sigurd, is easy to relate to and identify with. Considering some of the questions posed by Adrienne Shaw in Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender in the Margins of Gamer Culture about player identification, it is easy to see why Sigurd is such an enduring protagonist among Fire Emblem fans. Genealogy facilitates players having a comprehensive understanding of the character, “getting inside of the character’s head,” and wishing for him to succeed in his goals. Sigurd begins the game fighting against uncomplicatedly evil bandits who have kidnapped a friend of his unprovoked, and only seems to want to diffuse tensions with foreign lands.

The plot only becomes more complex, however, as Sigurd is left to question the role of interventionism while attempting to stop invasions from deeply complicated foreign lands. To tangle things even further, Sigurd is then falsely accused of the king’s death and forced on the run. This only makes it easier to understand Sigurd as a narrative character, as we find out more about his beliefs and goals through the dilemmas he faces, and get to know what the character is going through- most people can relate to being falsely accused, or feeling trapped in a difficult situation.

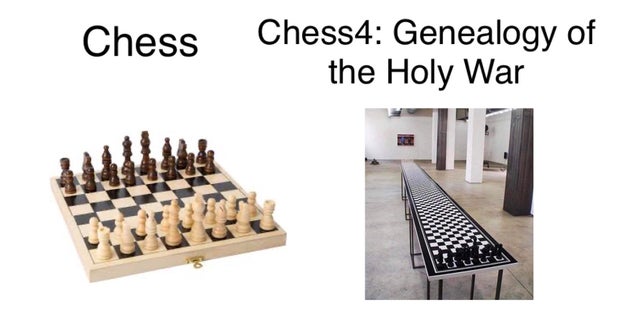

These feelings of identification are only heightened through the unique gameplay features of Genealogy, forming an enacted story. Genealogy is by far the biggest Fire Emblem game- while the average amount of tiles per map in other Fire Emblem games range from 400-900 tiles, Genealogy’s average is 4,000. This is especially shocking insofar as the Fire Emblem series already boasts far larger maps than most SRPGs.

Sigurd’s movement capabilities versus the entire map size. Sigurd is one of the most mobile characters. Let that sink in.

Levels of Genealogy regularly take about 5-9 hours to complete. Oftentimes, the sheer size of the maps causes gameplay to feel static. It is not uncommon for the next objective to be on the other end of those 2,000 tiles, and for gameplay to devolve into a pattern of moving each unit individually, waiting for the enemy to act, and repeating until the player eventually reaches enemies, for several hours at a time. This dull, repetitive motion makes the game feel very slow, as well as stretching out each level to a painful amount of time.

Yet, in the case of Sigurd’s story, this feeling may well be an enacted elaboration of what the protagonist is going through. Sigurd’s levels start out easy to traverse, but only get more difficult as the game progresses- in turn with Sigurd’s world becoming more complicated. Perhaps the demonstrated scope of the world encapsulates the helplessness he feels, and the slow, monotonous experience of being trapped- the player is forced to feel exactly as Sigurd is feeling, forced to flee to unknown lands and uncertain of what his future holds.

Via u/BroceNotBruce on Reddit

The length and difficulty of Genealogy is another way the player is encouraged to identify with Sigurd, or at the very least appreciate him specifically. Sigurd is by far the most powerful character in the game- he is mounted, meaning he is capable of moving over large distances (a blessing on these huge maps). Additionally, he has extremely high stats and growths as well as personal skills like pursuit, making him capable both of defeating enemies quickly and avoiding being damaged or killed by powerful foes. The player not only relates to and identifies with Sigurd in the story and gameplay, they also come to rely on him in-game.

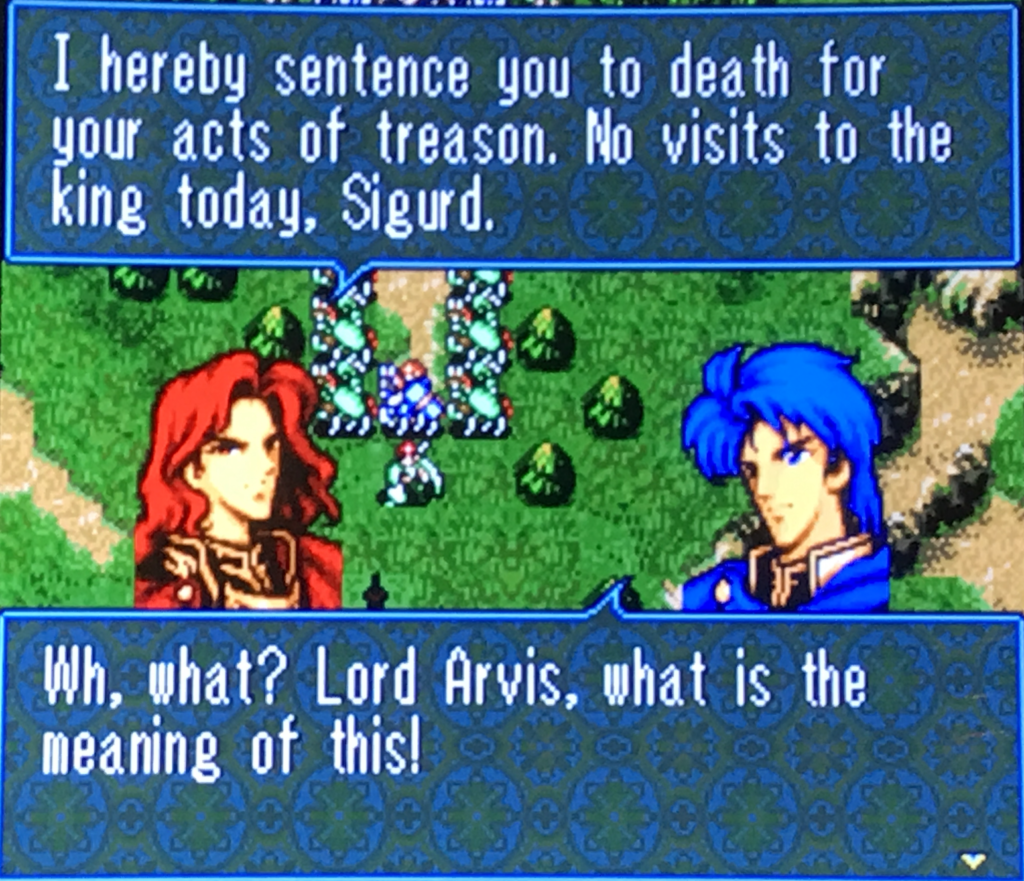

It is halfway through the game, as the player’s connection with Sigurd is fully formed, that Genealogy proceeds to delve into its famous plot twist. As I played the game, already very much aware of this iconic moment, I found myself wondering how audiences in 1996 reacted- for who would expect for the main villain to actually kill the protagonist?

Genealogy actually weaponizes the player’s identification with the main character to increase the weight of Sigurd’s death in the story. It is incredibly rare for any game to kill the main character (I personally have only encountered it in one other game) and intuitively, this makes sense. Killing off the player character is insulting and frustrating to the player. Removing the player’s avatar severs their connection to the game, and thus their identification with the events of the story, and arbitrarily destroys all of the player’s hard work invested into making the character better and stronger.

Yet, this emotional response to Sigurd’s death is precisely the point. The player feels the loss firsthand- they have become reliant on Sigurd in gameplay, and likely empathize with his tragic circumstances. This empathy only increases when he is unjustly killed.

Because the player used Sigurd as an avatar, the insult of his death is that much more personal- they have lost their representation in the game. The desire for revenge is externalized. Arvis’ betrayal is felt all the more deeply by a player who was helped by him firsthand, particularly as the sword he gifts you in the first level is useful throughout the entire game. Genealogy’s structure similarly capitalizes on this moment of betrayal, tying together the story event with gameplay. In the events of the story, Arvis has tricked Sigurd into surrendering and executed him, and this is consistent: Sigurd has surrendered the gameplay as well, as he is killed in a cutscene, where the player is powerless to stop it from happening. The unfairness is all the more potent, compared to an actionable battle against Arvis that seems winnable.

In most Fire Emblem games, player is told they desire revenge, typically for underdeveloped family members or people they never even meet. It is the opposite with Sigurd- the player’s connection to him runs through the story and the gameplay. Sigurd, as the avatar, is the player to an extent. His death is a deeply personal event. The player wants revenge for their own loss, even without the game commanding them to do so.

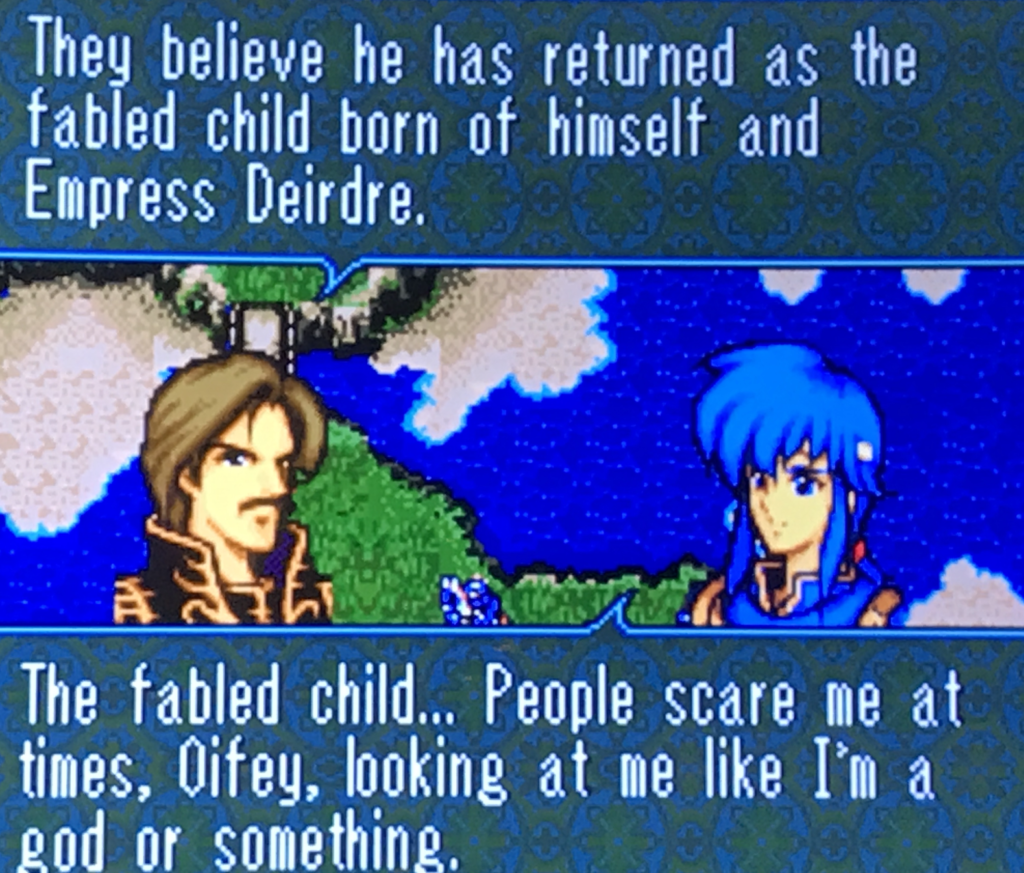

This theme of identification utilized in unique ways only continues into the second half of the game, when the player takes on the role of Sigurd’s son, Seliph, and pursues revenge against Arvis for Sigurd’s murder. Unsurprisingly, Seliph is also easy to relate to.

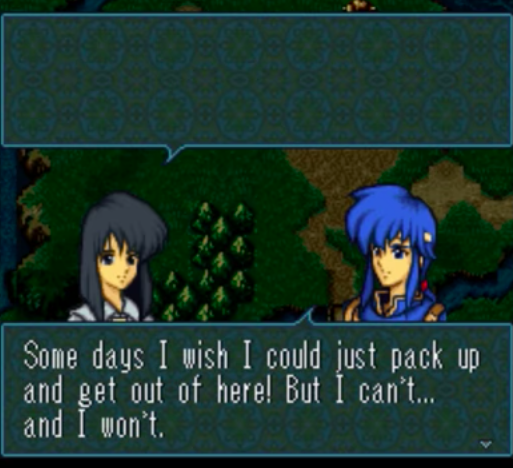

(He being Sigurd)

He is a seventeen year old with vast responsibility placed on his shoulders- a duty to avenge a father he never truly knew, and unseat the dark emperor bringing ruin to their entire continent. This feeling of high expectations, and anxiety about one’s own abilities is a common fear that many people can relate to. The gameplay is similarly utilized for relating the player to Seliph- his levels begin in the desert, the most difficult biome to transverse, demonstrating his fear and the weight of responsibility placed upon him. Additionally, when playing as Seliph, the player must start completely over- Seliph must begin from level 1, and is even weaker than Sigurd at the start, as he does not have a horse to traverse the maps. This emphasizes his journey into becoming a hero, and realizing his own destiny.

Ultimately, however, identification is a primary aspect of the way the game presents Seliph, something incredibly effective on a meta-level. Seliph actually uses the exact same battle sprite as Sigurd’s- and due to this, I often accidentally called him Sigurd. In this way, the game directly involves the player themselves in the narrative- not only is Seliph pressured by other characters to be more like his father and follow in the path they have assigned to him, but you, the player, want him to as well. I was implicated as soon as I called him by his father’s name, and anxiously awaited the day when he would rival Sigurd’s impressive power in gameplay.

Try and tell them apart. I dare you.

I acted precisely like the other characters in the narrative, but more than that, in a way that was actually opposed to the protagonist. This is the crux of what I find so fascinating about Genealogy’s protagonists and player identification patterns- it deliberately kills the player character and presents the player with a new avatar who feels forced into participating in the story- much the opposite to the player’s desire to avenge their own loss.

There is no option for the player to acknowledge Seliph’s aversion to violence or the lofty weight he is expected to carry simply by virtue of being born. Although Seliph ultimately succeeds in his goals, perhaps his half of the story can be viewed as just as tragic as Sigurd’s. It is through this unique approach to its two protagonists that Genealogy interrogates the role of the player in dictating the stories told in video games- asking which characters we identify with, and how our empathy might shift over the course of the game. It both presented me with a goal that I felt strongly about, and then called upon me to re-evaluate my assumptions. This is how Genealogy utilizes mechanics, art direction, and narrative to elevate video game form into an epic about fate, family, and identity.

Nicole,

I am so glad that there was another person in this class who wrote about the Fire Emblem series! Genealogy with its length is quite the beast to tackle, and you did such an excellent job on condensing such a long game into a thoughtful analysis on its characters and mechanics. As my discussion post delved into what makes the first Fire Emblem game what I consider a true contender for the “slow genre”, I have found a lot of additional claims within your argument to further back up this idea as being applicable to the Fire Emblem series as a whole. Your use of the direct average tile per game was fascinating, and I love the interwoven discussion with how that affects gameplay, characters, and story. Few could argue with just how methodical one has to be in order to get through this game; thus, Genealogy can serve as a crown jewel into the discussion of “slow games” and their engagement levels with the medium.

(PS the chess memes that are a commentary on the length of Genealogy’s maps made me laugh way to hard XD)