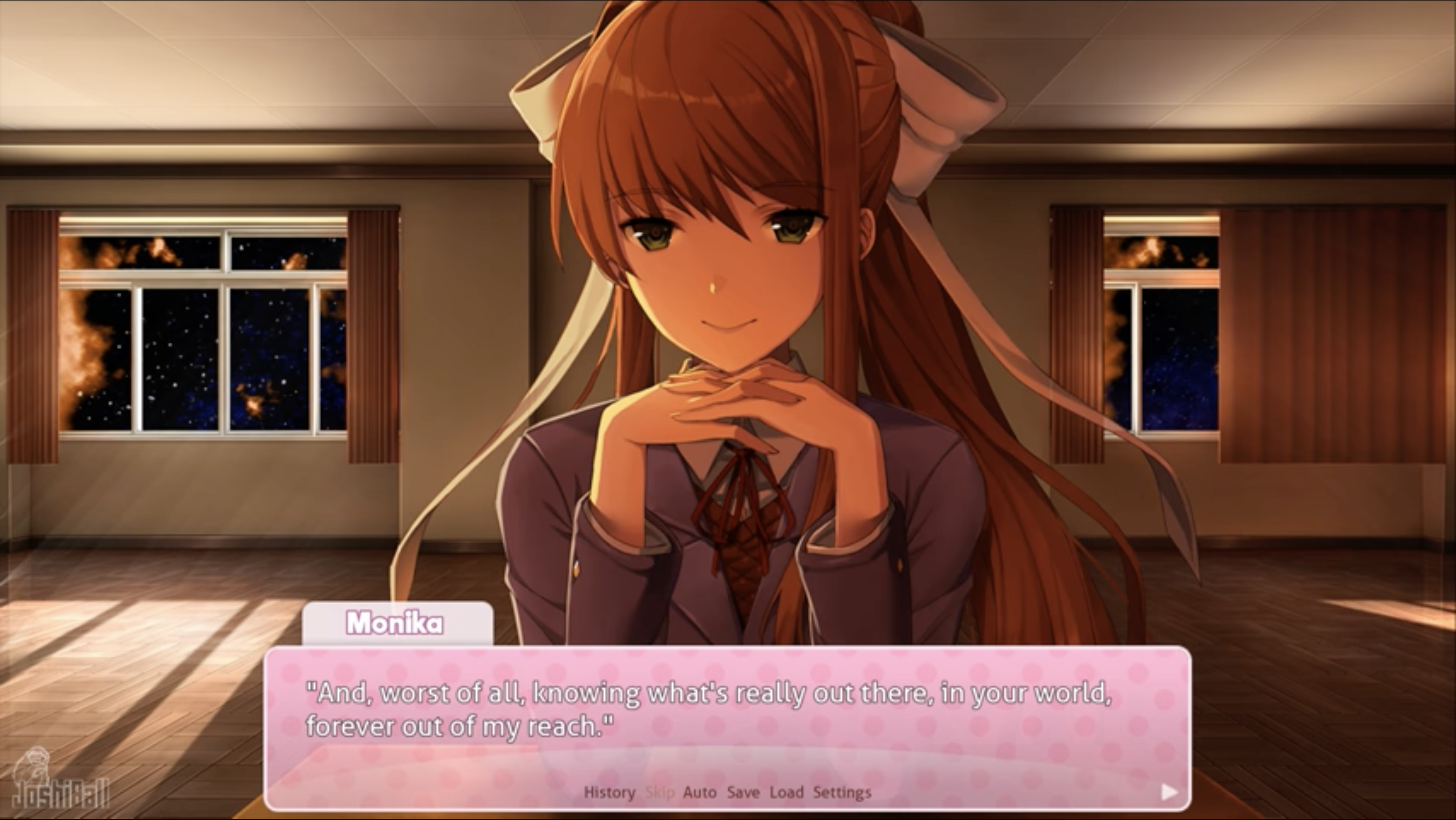

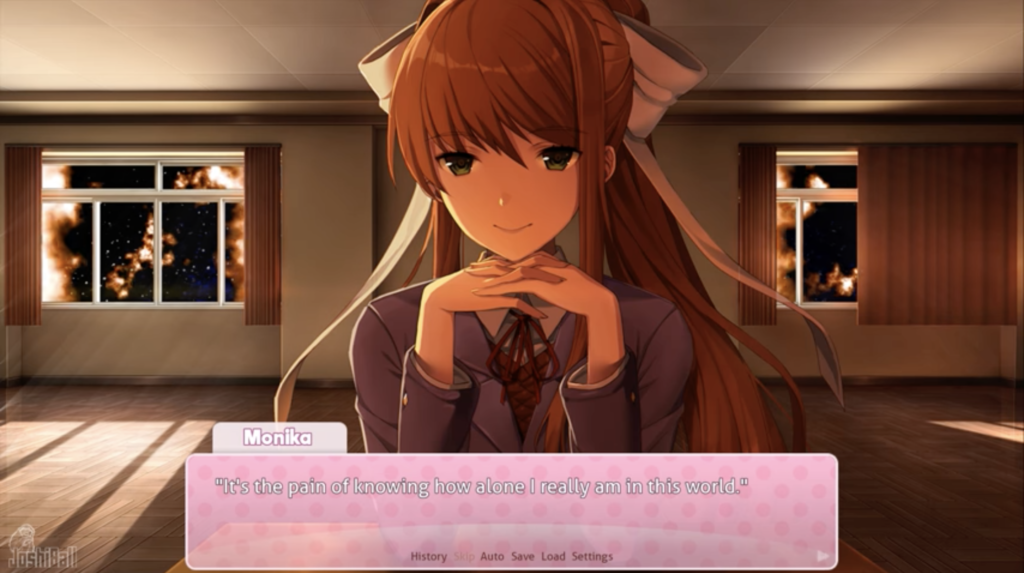

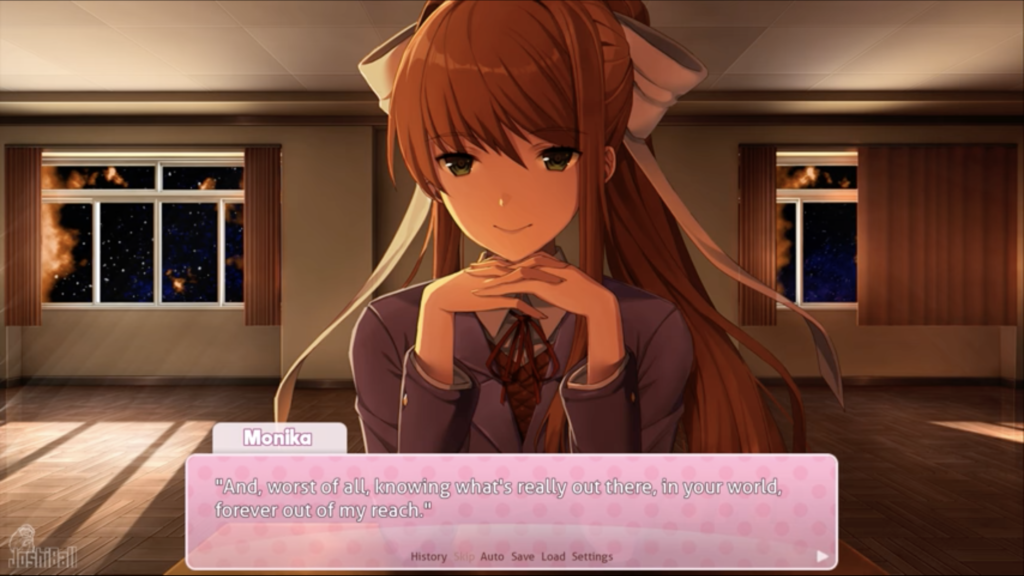

The first referent I thought of when I played Doki Doki Literature club was actually Shakespeare’s the Tempest. The meta-ness of both is obvious: Both “plays” take place within a unique, specific place that references the space of the medium, where a central character who wields unbounded power attempts to “correct” a course of events. In The Tempest, it is Prospero, who acts akin to a playmaster and uses his power of angels and spirits on the island to direct the play in his favor and restore himself to his throne. In DDLC, it is of course Monica, who wields absolute power in the space of the game, and, not unlike Prospero, tries to use this power to tamper with the other characters and steer the course of events in her favor. Both characters lose their power outside the space of their medium — Prospero relinquishes his power as he leaves the island, while Monica could not stop the player from deleting her file, which lay outside the game.

What was particularly interesting though is how the two diverge. In the epilogue of The Tempest, Propsero breaks the fourth wall like Monica and asks the player to set him “free”: “I must be here confined by you / or sent to Naples. Let me not / since I have my dukedom got” (1). The power to end the show is artificially granted to the audience. What is special about Monica, however, is that whereas Prospero uses the island/theatre as a tool to bring him back his “real” life outside the island/theatre, in his dukedom, Monica has nowhere else to go. In fact, she almost broke the only world she could live in for something outside it, the player. Because of this, Prospero succeeds while she fails, as she has no power outside the space of the game. If we make the claim that Prospero used the space of the island — an unreal and magical space — to restore the political order of the real space (his dukedom), then for Monica real space and unreal space is hopelessly superimposed onto one another in the 2D surface of the visual novel, leaving no “other” realm for a happy ending to exist. In the end, she destroys the entire game, in a gesture of relinquishment much more powerful and complete than that of Prospero.

The differences in affect between the two is obvious due to the characteristics of their respective mediums: DDLC creates a much more intimate connection (and disconnection) with the audience compared to what is possible for a theatre house. And whereas the audience of a play could maintain a safe distance with the characters on stage, the 2D layers of the computer screen breaks apart and collapses under Monica’s manipulation of the GUI and the HUD. The last thing she can do would be to crawl out of our screen like Sadako. This breaking down of distance between the player and the medium-space, however, is also what lead to Monika’s failure to unite forever with the player, as we were able to interact with the very materiality of the medium and interrupt it directly. Thus, this distance exists not only to keep the audience safe from the horrors on the stage, but also to keep the characters on stage safe from the manipulation of the audience — hence the success of Prospero and the demise of Monika.

- Shakespeare, William. The Tempest, Folger Shakespeare Library, https://shakespeare.folger.edu/downloads/pdf/the-tempest_PDF_FolgerShakespeare.pdf (Accessed October 26, 2021).

- Joshiball – No Commentary Gameplay. “Doki Doki Literature Club (Full Game, No Commentary)”, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msc1n57t-L8&t=52s (Accessed October 26, 2021).