Both consent and The Stanley Parable (hereinafter TSP) center around issues of agency, ethics, and power. TSP provides complicated implications of how consent is obtained, applied, and sustained. This blog post only covers tiny examples that add to the discussion from class, so please feel free to point out many others.

It is important to first distinguish between various common conceptions of consent in how the concept plays out in video games and TSP. Interactions and values fundamentally alter the form that consent plays out, wherein consent can take the forms of negative or affirmative attributes. In “Challenges of Designing Consent,” Josef Nguyen and Bonnie Ruberg describe these two forms or models as a “negative model (‘no’ means ‘no’) versus an affirmative model (‘yes’ means ‘yes’).” While of course, the affirmative model is the ideal that informed consent entails, the reality of interactions makes it so that we must consider how video game mechanics and narratives utilize either model of consent.

TSP’s opening narration and introduction to the game’s mechanics demonstrate a shift in the consent agreement between the company and number 427. Up to the start of the game, Stanley had granted his employer consent to him what buttons to press and for how long. The absence of instructions to continue this task is a negative model in which Stanley then has the agency to do other tasks (or at the very least walk around).

But of course, Stanley is not able to explore freely, as the narration provides the player with continuous moments to negotiate consent. Crucially, if the narration says that Stanley will enter the door on the left, but the player chooses to move Stanley to the right, what does this say about the interplay of agency and power between the player and the game? Moreover, if the game’s narrative is built around the irony that you will most likely break the trust of the narration’s plot line, and hence provide even more forms of gameplay, has any ethical ground actually been broken? I would argue that the game implores the player to consider not only the impact of disregarding the inverse of negative models of consent but also the narrative consequences of those decisions.

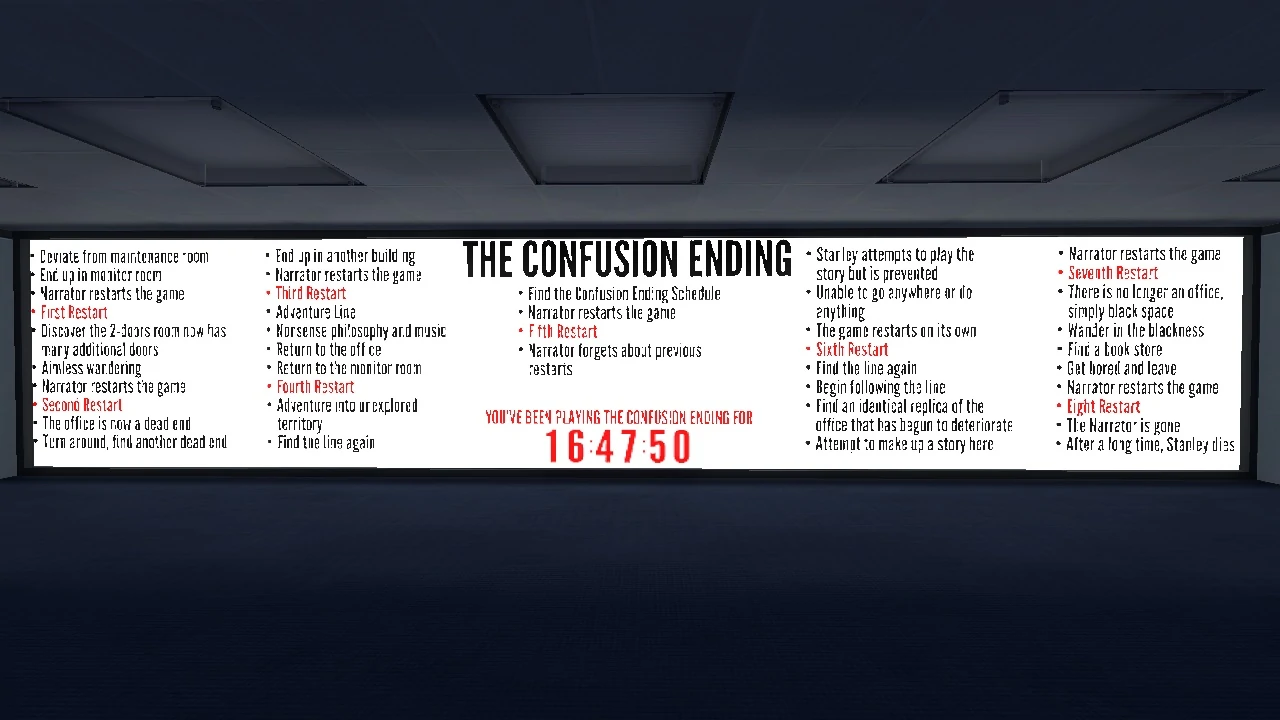

With the game being self-aware of its relationship to the player, it is interesting that there are moments in which the player’s consent is disregarded. Game mechanics are traditionally set on the player having control over settings that allow them to restart and power off, yet TSP plays with taking that power away from the player. In what the game’s wiki calls the “Confusion Ending,” there are times when the game will reset without the player’s consent, or restart in ways that are unexpected and hence not in line with the agreement between the player and their expectations of the game. Further complicating this dynamic is the fact that as the game grew in commercial and critical success, the various endings have themselves become the desired outcome. Again here the game is able to provide a meta-narrative on what occurs with consent as it shifts through cultural norms and values (in this case of its player fanbase). How effective this ironic narrative is–or my quick analysis of it–is certainly up for debate!

Work Cited:

Josef Nguyen and Bonnie Ruberg. 2020. Challenges of Designing Consent: Consent Mechanics in Video Games as Models for Interactive User Agency. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376827

(Featured image from https://gallery.neoseeker.com/Shadow%20of%20Death/photostream/3416771811)