Spoiler alert: the protagonist of Jonathan Blow’s Braid is not the good guy. In a final level that has gained renown from casual gamers and critical game scholars alike, the platformer’s fundamental mechanic of time manipulation is used to show Braid’s suit-clad protagonist, Tim, chasing after the princess as she runs in fear and obscures his path with traps and various pitfalls. By turning the time-worn tale of a man searching for his damsel in distress into a more thought-provoking, modern take, wherein Tim himself is the enemy rather than the hero, Blow’s Braid distinguishes itself from other games of its contemporary by undoing any attachment players may have to the character they control. Though there are innumerous interpretations of the game’s ending, in each of them, Tim takes on the persona of some kind of monster– but does it really take the entire game to figure that out, or are hints dropped from the very moment the tutorial begins?

Against the backdrop of sunlit, watercolored clouds, the first thing a player learns is that Tim is off on a search to rescue the Princess, snatched by a “horrible and evil monster” of unclear origin because Tim made an equally unclear mistake. But then the game elaborates that it wasn’t just one, it was many– a whole relationship filled with Tim’s “guilty lie[s]” and “a stab in the back.” The princess grows more distant until finally, she turns away from him completely. Nothing else is given about the terrible monster that snatched the princess away– instead, we learn Tim’s attitude toward mistakes. “If we’ve learned from a mistake and become better for it, shouldn’t we be rewarded for the learning, rather than punished for the mistake?” the text reads, implying that in any of the prior narrative, we see a glimpse of Tim growing from the mistakes he made. The first– or rather second– world’s prologue ends with the tableau of Tim and the Princess sitting together, “their mistakes… hidden from each other, tucked away between the folds of time.”

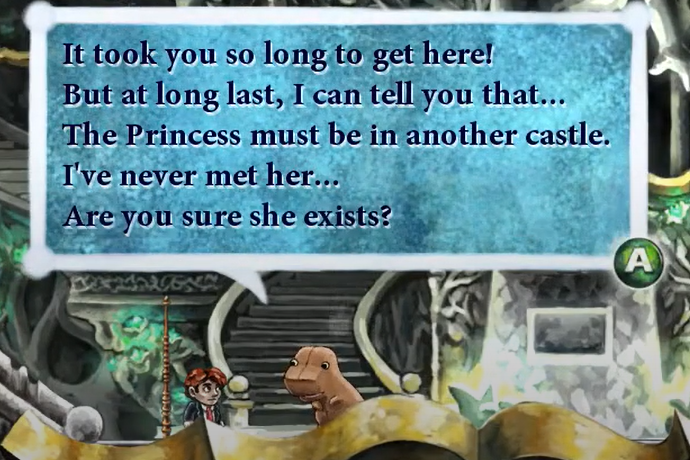

From there we learn that Tim is essentially an immortal being who cannot die, having mastered the ability to rewind time. He goes on an adventure and kills a myriad of creatures, his only positive interactions coming from the greeter who– following the game’s narrative– similarly begins to distrust him.

With all of these things combined, in addition to the increasingly mysterious circumstances surrounding Tim and the Princess’s relationship at all, it was hard to have faith in the character that I controlled. His powers would grow with each world, as would the uneasiness in the back of my mind that maybe his obsession with the princess after she turned him away was unhealthy and even predatory. In the final world, we learn that Tim wants “like nothing else” to find the Princess, and that this occasion would be “momentous, sparking an intense light that embraces the world, a light that reveals the secrets long kept from us, that illuminates — or materializes! — a final palace where we can exist in peace.” This in tandem with the greeter character’s doubts that the princess even exists was enough to put me over the edge in my complete distrust for Tim, if that’s even his real name. It seemed like an obsession rather than love, especially given what I knew about Tim and his “mistakes.” Why would he betray someone who seemed to mean so much to him if he truly cared for her? And why would he bother to go through such a perilous journey when, during their relationship, he didn’t even show her human decency?

Perhaps it takes a certain cynical outlook to view all of these things together as red flags. Some could argue that beginning the game with the admittance of Tim’s mistake is humanizing, since who among us hasn’t accidentally hurt someone we care about? But with everything combined– namely, the clear depiction of his abuse juxtaposed with the murky circumstances of the princess’ eventual “capture,” his character’s intrinsic inability to own up to mistakes, and even his interactions with other beings made the ending not quite the surprise to me that many other gamers had.

I think it’s amazing how a game manages to make me question the protagonist with just design mechanics and its setting. Even in the first few screens, the graphics, sounds, and design of the game just gives off this uneasy feeling. The protagonist looks to be this average working class man in tuxedo, dispositioned in a fairy tale land with fantasy elements. Everything around me makes me feel as if I don’t belong here. The music, too, strengthens this disparity, by layering traditionally eastern musical elements on nostalgic strings. This juxtaposition of style in various is indicative to me the narrative dissonance, especially undermining my trust in the protagonist.

This is honestly one of the most interesting things I’ve heard someone mention so far about the game; I think this is an example of just how important the use of a protagonist is in video games, and how the creators of a game may intentionally include details such as the ones you mentioned to make us question how we feel about the main character. Even further, this happens with antagonists, and other supporting characters too. Some games rely on a plot twist that reveals more about characters we thought were evil, and completely inverts our perspective on who’s right and who’s wrong (one game series that comes to mind is the Far Cry series, especially with some of the secret endings). I think sometimes that can be a very useful way of making a statement about certain ideals, values, and even morality to a certain degree, and maybe challenging our pre-existing notions about them in the same way that Braid does with Tim and the Princess.

I do agree with you in how it is interesting that Braid makes players rethink the main character and the motives behind their goals. When I played Braid, I came to the conclusion that, no, we aren’t supposed to like Tim, because of what he has done and what he plans to do in regard to the true interpretation that the princess is a personification of the Atom Bomb. Tim’s character and the way that Blow frames the entire narrative leads me to believe that Blow himself was against the implications and the effects that the Manhattan Project had on the world. The sense of not belonging that is present within the game also led me to believe that Blow was trying to say that man does not belong in the realm of creating nuclear destruction.

“It was hard to have faith in the character that I controlled.” I think that this is an interesting conversation, namely because you discuss Tim’s actions as if you (the player) are removed from them. Obviously, I’m not implying that you would drop an atomic bomb or mess up your relationship if given the chance, but it’s worth the thought to try implicating yourself in the consequences of the game. There are physical signs telling you/Tim to stop — the flags at the end of each level, the enemies placed in your path to make it difficult to advance — and yet you continue, not knowing the consequences of your actions but still curious about the outcome of them. Maybe you just weren’t paying attention to the signs, but that still doesn’t make you exempt from the ultimate consequences of the game (the bomb dropping, if we’re going with that theory). You, the player, make many mistakes — thankfully corrected using the time reversal mechanic — just as Tim made many mistakes in his tumultuous relationship with the Princess. In some sense, perhaps the red flags that you discuss could be just as much your cross to bear as their are Tim’s.

I dunno, though! The discussion of chronology is a whole other can of worms that I feel like would also feed into this discussion of good and evil. It’s just a really, really cool game, and this was a really, really cool discussion post about it. :>

Like many others, I felt very out-of-place as Tim, Mr. Man In a Suit, in a world of fantasy. And especially after learning about the ending and the meaning what everything represents, it really hammers home the idea that we are not wanted in this world. We are constantly being worked against which doesn’t seem wrong because that’s what most games do. The classic adage of “If you run into enemies, you are going the right way.” Usually there is some reason why we are “the greater good” but Braid takes advantage of that and warns us that not all protagonists are good. You mention the text about being rewarded for growth is very interesting to look at in terms of the game mechanics. Some things don’t change when you go back in time to learn from your mistakes and sometimes people forget that mistakes aren’t a closed loop. They still have consequences, even if we can bend time to make it look like we were changing.