When doing our readings this week, the one that sparked me the most was Wolfs Theorizing Navigable Space in Video Games. As a second year, I’m currently in the spatial analysis SOSC, and so this reading really grabbed my attention. I never thought I would be taking two classes with such a majorly different focuses, and finding such a similarity in them. Realizing I could analyze video games from a spatial aspect excited me; I’ve found a new application for a concept I’m spending three quarters to learn about. When I thought about what game really piqued my interest this week, DOOM immediately came to mind. I never knew DOOM to be such an influential game, and having played it now, I completely understand why.

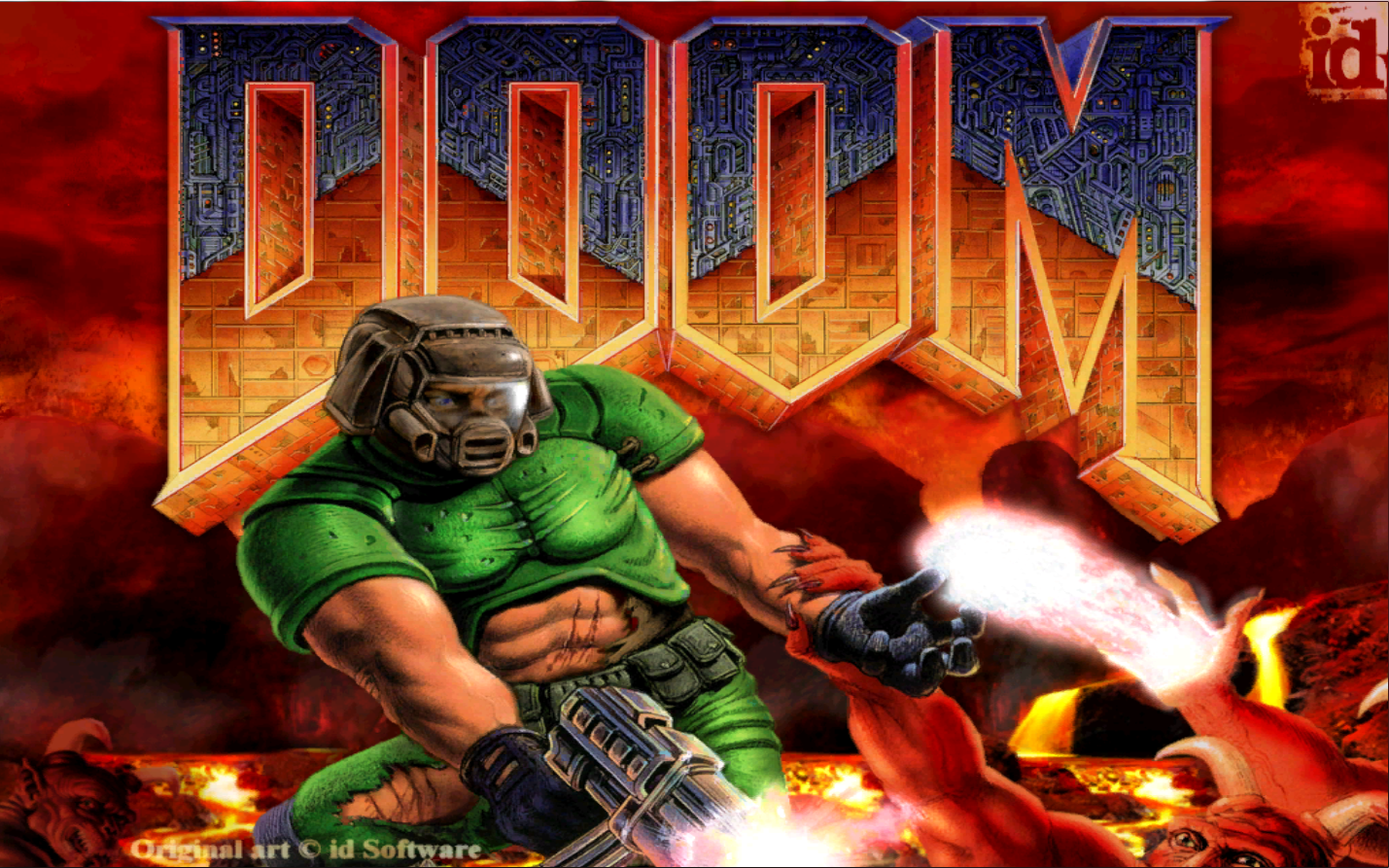

When you first open DOOM, you feel immediately immersed, as the home screen is a beautifully depicted representation of what the game is. You see your character engulfed in red, as he has to literally escape hell itself, kill monsters, and be some sort of hero. Then, as you press single player, clips of gameplay take over the screen, allowing you to be ready for what you’re getting into. You get to see some of the different areas, the monsters, and with the music in the background; the intensity of the game.

The character information is able to pull you in even further. At the bottom of the screen, you see your character’s face. You get to see his expressions: his excitement when finding a new weapon, his pain as he takes more damage, and even just his face as he explores each level is interesting. You can sympathize with your character, making you feel the same emotions as your character and make you feel yourself within this game. This was so important for it’s time as they were so heavily focused on pubescent boys; they wanted a game where this child could feel himself in the game. They want these teens to want to be the character; to feel cool and strong and “manly.” I feel that this immersion helps them achieve their goal.

The world of the game brings everything together. Each different section of the game is designed to represent the names of the chapters, effectively adding to the story. The first levels make you feel like you’re in this space laboratory of some sort, trying to escape. The second map truly feels like hell, with lava patches and a dark red theme. It goes on and on with each new map representing a new area. They create dark spaces, making it scarier as monsters come from nowhere. You don’t even realize it sometimes until they start attacking, like with the monsters that shoot fireballs. I found myself jumping many times as I ran into a monster randomly.

To push it even further, they have an amazing soundtrack and amazing sound effects to add to the game. You can hear the monsters around you, so you know to be wary. You get to hear yourself, the doors open and close, the elevators move up and down, and more. They make sure there are sound effects for everything. They also make sure the music is intense and fitting, furthering pushing this “manly” and “tough” agenda on their targeted audience.

Ultimately, there is so much that goes into DOOM that makes it the influential game it is. However, it would not be the game it is seen as today without its immersiveness. The depiction of the character, the amount of detail that goes into the settings, and the music all help it effectively achieve their purpose of pulling a person (presumably their teenage boy targeted audience) in. I would love to hear anyone’s thoughts on DOOM or spatial analysis in general!

I like your point about fear and dark spaces. You can really see this in action toward the end of the Phobos Lab level. There’s a section of the map that is almost entirely absent of light. The room is pitch black with the occasional flash of light. The room itself seemed to be circular and more symmetrical than most of the other sections. The lighting combines with the room layout made this section disorienting and scary. Since the mechanics and types of enemies did not change, the increase in fear is solely attributed to the way space is utilized in this section. The emotion of this section is derived from the space.

It’s interesting to consider space and sound, especially given Doom’s position as one of the early 3D fps games. Detecting monsters from different corners using sound, and how this can add to and change the space one occupies, or even the way sound can allude to space that is not available to the player adds another layer of depth, a concept certainly built upon by later games.

I think your post is very interesting, and something that intrigued me while playing Doom is how much your brain works in to fill the gaps left from technology. Obviously it’s not a perfectly accurate 3D render of the game world, but because of the immersive environments you describe, your brain automatically fills it in.

I think the link you’ve drawn between immersion and gendered appeal is really interesting. Like you’ve argued, Doom appeals to young boys by presenting an image of masculinity they’re taught to aspire to, and letting them actually sit in that identity from a first-person perspective might be among the ultimate experiences of the fulfillment of that fantasy. I think this might even go a step further, though. Is there some extent to which the first-person perspective itself can prioritize masculinity due to cultural biases? Thinking about popular 1990s literary fiction, this list: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/the-read-down/20-bestsellers-published-in-the-1990s/ of 20 of the most successful books published in the 90s includes a few notable examples of books that have been interpreted (regardless of authorial intent) as similar first-person (or third-person but with close proximity to the mind) masculine power fantasies, including Hannibal, American Psycho, Holes, and even Jurassic Park. I’m not sure how exactly to describe it, but I’m interested in how the masculine power fantasy has enjoyed a cultural vogue since the 90s as not only a character study (like the Rambo or Rocky series prior) but as an active and maybe disgusted “psychological study.” Also Batman.

The use of light, sound, and the cramped and maze-like 3D environments honestly sell DOOM almost like a horror game, doesn’t it? I mean, the game (and eventual series) itself is an action-FPS that prides itself on its main character being a badass (brought up when mentioning how the game appeals to masculinity), but it could very easily become a Silent Hill-esque survival horror game with a different main character. I think that adds to the appeal, the hostile environment of the game adds to the adrenaline rush of playing as this one-man-army.