Games often have literary plot that guides and informs gameplay. The literary plot is usually intertwined with the rest of the game play, including setting, characters, and music. Through these cues, the player is able to get a feel for what the game is about and how they will interact with the game.

Although games can put so much effort into world creation to make you perceive the game’s world exactly as the creator intended, the way in which you ultimately perceive the game can be changed greatly by preconceived ideas you bring into gameplay. These preconceived ideas can form in a variety of ways: opinions you hear from friends, how you feel toward a certain color palette in a game, or what genre the game is classified under.

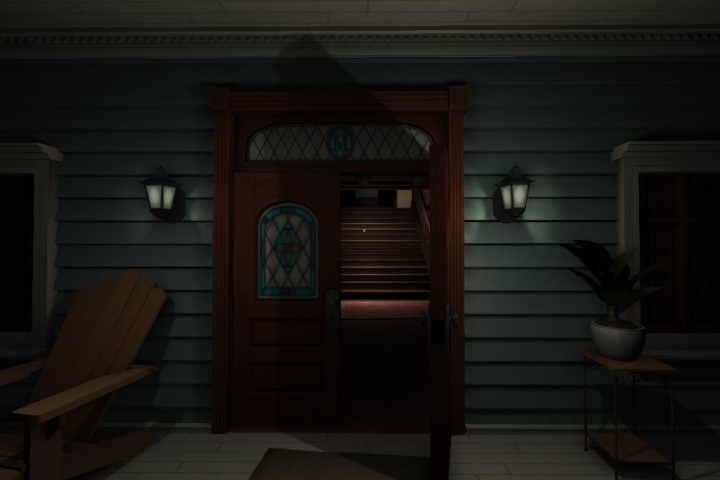

My experience of playing Gone Home, an interactive exploration simulator according to The Fullbright Company, the developer and publisher of the game, was completely different from that which it was supposed to be. After taking a look at our class topic for third week and seeing that it was horror games, I assumed the games we were playing would be horror games as well. With this genre classification in mind, I strengthened my heart and entered the world of Gone Home, preparing for jump scares and expecting to find a murdered body in the master bathroom.

At first, the horror genre that I believed the game to belong to didn’t seem so far off – it was storming outside, there were creepy notes spread throughout the house, and the house was dimly lit at best. Yet, being (falsely) aware that this game fell into the horror genre, I completely avoided exploring the first floor since the hallway was too dark to see anything through. I thought there might be something waiting to kill me in the dark or that I would find a flashlight at some point, so I explored the entire rest of the house, including the second floor and secret passageways, before making my way to the first floor after finding the light switches to illuminate my path.

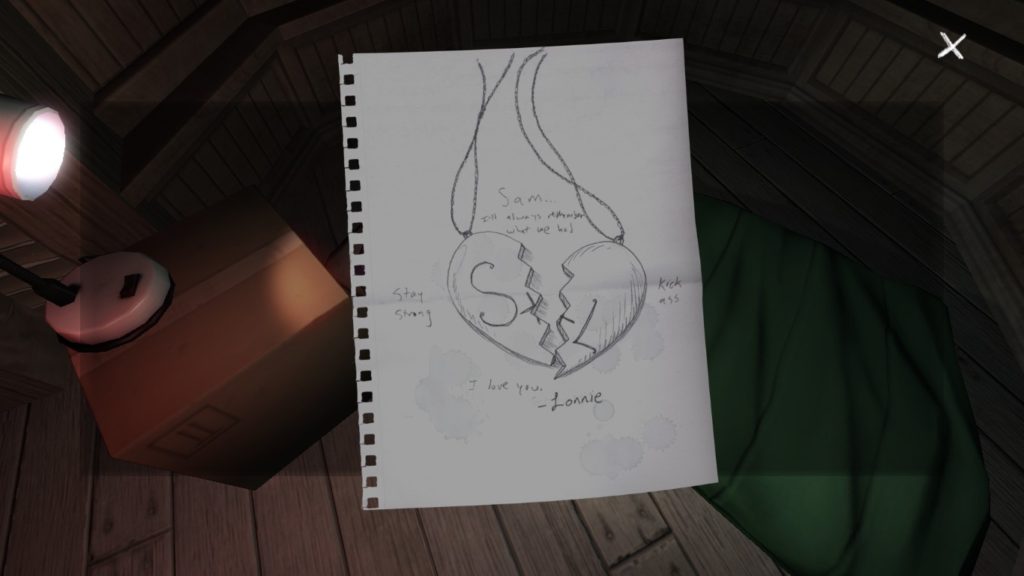

If this were a game simply about jump scares and meant to cultivate a horror experience, maybe my avoidance of this hall wouldn’t have been so significant. Only after returning to the hallway I skipped over did I realize that I missed the entire beginning of the story line around Sam and Lonnie. I knew that they became friends but was unsure how they met. I didn’t know about Sam’s history with transferring to the school and being asked rude questions about her uncle by classmates. All of this important background ended up being something I discovered near the end of my gameplay rather than at the beginning to serve as exposition, all because I was afraid of walking down a dark hallway.

If my own preconceived notions about this game completely changed what experience I had with it, from changing the order in which I discover routes in the game to my fear of entering rooms, then everyone’s life experience changes how they interact with games. Although the game creator and/or developer may try hard to create a “correct” path through which you play a game, whether that path is followed is ultimately up to the player and how they believe they need to play a game. Although I don’t believe there is a step-by step order in which information is supposed to be discovered throughout Gone Home, I do believe there is a general order, such as discovering the first floor before moving up to the second, as suggested by the way background information is given on the first floor while the plot thickens and further develops on the second floor or in deeper rooms.

For me, Gone Home started out as a horror game that unraveled into a complex mix of stories across a family dealing with abuse, acceptance, and infidelity. For someone being directed to the game from the developer’s website, it might be exactly what they expected as an exploration simulator. This game can be many things at the start of it (or most of it for me) and fit into many genres depending on what information the player enters the created world with. Although my experience with Gone Home might hurt the proceduralist reader, at the end of the day, the player has immense power in how a game (specifically simulations) is interpreted and further played – for better or for worse.