As we’ve seen in recent classes, the world of video games offers a plethora of ways to die. But death or failure can mean many different things depending on what game you are playing. Today I’d like to ask a seemingly simple question: why do we die in video games?

At first glance, death serves a simple purpose in most video games. Without some kind of failure state, a player won’t feel much achievement upon succeeding. The risk of death raises the stakes of the game and gives us a reason to put effort and skill into our play. But some modern games have evolved to use death as a central part of the game experience, rather than just as a necessary mechanic.

Enter the roguelike. I don’t want to wade into the weeds of defining this genre, so I’ll simply say that in most roguelike games, it is impossible to win without dying. Most roguelikes require the player to build their knowledge and skill through repeated attempts that invariably end in death. Some, such as Dead Cells and Hades, actually reward the player for dying. These games give persistent bonuses and powers to the players that follow them past death and are built up through repeated runs of the game. Thus, roguelikes invariably require their players to embrace death, to treat it as a necessary part of the path to victory rather than a frustrating setback. In this sense, death in a rogue like isn’t really a failure state. Every death is just another step towards winning.

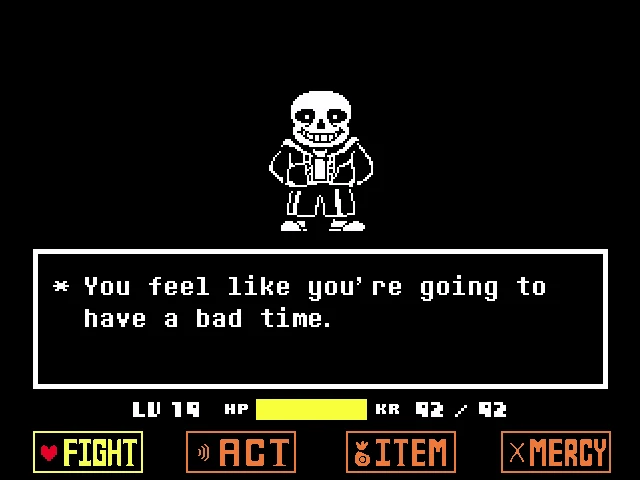

There are plenty of death-intensive video games where death is fully a failure state, though. Many games are built to be so hard that it is impossible to beat them without practice, such as the infamous Dark Souls games and the (controversial) subgenre it has spawned. Like a roguelike game, Dark Souls requires the player to practice fighting its many difficult bosses to acquire experience and skill – and to die many times in doing so. (Again, I don’t want to wade into the genre wars, so I’ll uses “soulslike” here as a loose label for games that require intense skill and practice to beat and do little to help struggling players. Obviously, this label could encompass a very wide variety of games.)

Unlike a roguelike, Dark Souls does not directly acknowledge the importance of player death. Instead, it punishes you for dying, removing your resources and forcing you to recover them. What this tells us is that there is little mechanical difference between death in roguelikes and in soulslikes. Where these games diverge is in how they make the player feel about death, whether they acknowledge that it’s a necessary part of the process and encourage the player to keep going or simply ignore it. After all, it’s much easier to rage-quit Dark Souls after dying several times and making no progress than it is Hades, where the game unlocks new content and rewards every time you die.

So why the difference? Loyalists of the soulslike genre would argue that its level of difficulty is an essential part of the game, that to be forgiving of death would undermine the difficulty and thus lower the psychological reward of success. While there is undoubtably some truth to this, I think there also a large element of player choice. Some players want to feel like the game they are playing is challenging but fair and helps them to improve upon their failures. Others want to feel solely responsible for every victory they squeeze out of an unreasonably punishing game. Both roguelikes and soulslikes can be very difficult, but they approach that difficulty in opposite ways and thus attract different kinds of players. Ultimately, asking why different video games offer different experiences of dying leads us to a much broader question set of questions about the players of those games – including what makes for a “hard” video game? What expectations do players of hard video games have? And why do people play hard video games at all? I hope to address some of these questions in future blog posts, and I welcome commentary on the ways in which different games approach difficulty and death.

Image credits in order:

https://www.keengamer.com/articles/features/opinion-pieces/hades-and-the-dance-of-death-in-roguelikes/

https://undertale.fandom.com/wiki/Sans/In_Battle

https://darksouls.fandom.com/wiki/Death

I really loved the important questions you raise about difficulty as a game mechanic. In this case, you talk about how the way in which permadeath punishes players changes players’ expectations and feelings of reward in the game. I think the same concept can also be applied to game modes offered in some titles. For instance, Fire Emblem Three Houses offers players the choice before starting whether to play with Permadeath (like most Fire Emblem titles) or to play in a Casual mode where characters return in subsequent levels.

Something to consider is why do game designers make the conscious decision to offer multiple different difficulty levels if doing so will change the way in which a game is played?

This is a great point! I’m actually hoping to consider difficulty levels in a future blog post, with an eye to examining games with ironman or permadeath modes, and games where the player community invents new challenges.

I really enjoyed your post as I think the discussion of difficulty and its role in shaping player interaction is incredibly interesting and critical to genre identification. I was particularly interested in your point about rage-quitting as being more likely after dying in Dark Souls than in Hades. I think anger and frustration are also important components of many game experiences, and can be both discouraging or enticing depending on the individual player. I’m extremely curious about this distinction. When is frustration enjoyable versus experience-ruining? Does a player’s experience of frustration depend more on the game or more on external factors beyond the game’s control (player’s mood, play style, etc)? How have game designers innovatively utilized or incorporated player frustration into their games’ structures?

I find the difference between death as a failure state and death as a method of progressing really interesting, particularly because you seem to imply that in games like Dark Souls it doesn’t use death for progression. I remember my first time experiencing Dark Souls, a friend of mine from middle school was trying to show off and got killed, after that he said, “Death is the tutorial here, it tells you what not to do.” I think that mentality is pretty spot on, since Dark Souls bosses are mostly designed to be unwinnable through pure dexterity and mechanical knowledge, as they almost all require you to learn specific tells, wind-ups, and patterns, or they ‘re unwinnable. In this case, the only way to learn this is to go in there, die, and learn.

So I guess I’d question, what kind of benefit does a game need to give you for a death to be considered more than a failure state? Does it make a difference if that knowledge you gained is an important part of the narrative, like in Undertale? Do you need to be actively rewarded for dying, like in Hades, or just not have all your progress reverted, like in Dead Cells? What about intentional deaths that weren’t necessarily meant to be beneficial, but can be exploited for purposes like death warps or death heals?

Overall, I think there are a lot of ways death can help us in games, and even in games designed to punish you for dying, there’s often lots to be gained from them.

The post and the comments are all very insightful! If we want to put this on a macro scale, I think a video game is this important medium that allows humans to touch death, interact with death, and experiment with death in a way that no other medium possibly can. It brings us closer to this traditionally uncanny and kinda forbidden topic that is not usually experienced in our daily life (well no one knows what it is like to die unless you die). In this way, how death is used/narrated in game mechanics may serve as a kind of reflection of our inner interpretation of death or expectation. E.g., death is a reward. Death is a danger. Death brings you back to life. You have to “die” in order to get what you want, etc. Games remediated death, an uncanny topic, in its mechanics and allowed us to play with it, maybe even appreciated it, which crafted a kind of new experience for our life.