The Fool’s Errand is a 1987 meta-puzzle game created by Cliff Johnson for the 1984 Apple Macintosh. In it, the player unravels the non-linear story of The Fool’s journey through the Land of Tarot through a series of challenging word and picture puzzles, slowly revealing The Sun’s map and collecting the fourteen treasures of The World. The Fool’s path is not simply traveled, however, as beyond the puzzles obviously presented to the player, they must find hidden clues within the text of the Fool’s story, re-order their scrambled map, and uncover the High Priestess’s evil plot for the Book of Thoth.

The first time I played The Fool’s Errand, I was so frustrated. The minimal, dithered art style was cool but hard to parse at times, the puzzles had little to no explanation, and the retro interface just felt annoying and clunky (I was 12 or 13, I didn’t have quite as developed of an appreciation for retro tech at the time). I kept getting stuck on puzzles that seemed completely impossible to solve, and I felt so turned around by the non-linear, disjointed, cryptic story. But then, suddenly, as I accidentally moved my mouse too far and misclicked on one of the game’s menus, I had one of the most profound Eureka moments I can remember. I won’t spoil the details here (go play this game!! It’s excellent!!), but I realized that this cryptic, seemingly nonsensical puzzle required me to manipulate the interface of the game – the dropdown menus themselves – to solve the puzzle. And instantly, everything started to fall into place. I realized that all of this game’s weirdness and inscrutability was not just random or archaic (again, I was 12, 1987 may as well have been Triassic to me), but it was the game demanding that I break out of my expectations of the bounds of its puzzles and see every piece of information presented to me – not just the ones that seemed puzzley – as significant. This moment completely changed the way I see and appreciate puzzles in games, and made me totally fall in love with the meta-puzzles.

I have talked about The Fool’s Errand a number of times in class, and I bring it up incessantly when discussing puzzle games with my friends and fellow puzzle-gamers. While my endless chatter about this obscure computer game from the 80s may be annoying, I really do believe this game was very significant in the development of the modern puzzle game landscape, and its distinct style and approach to puzzling continues to echo through puzzle games to this day.

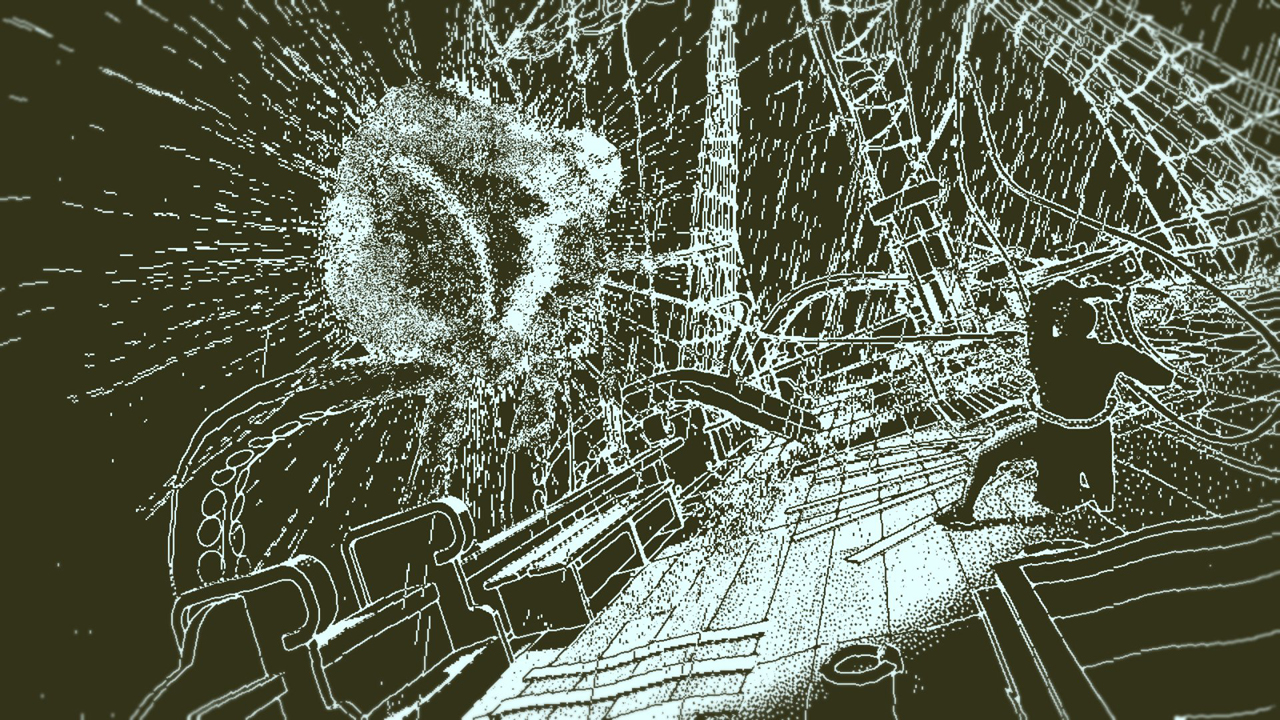

When we played Return of the Obra Dinn, I was instantly reminded of The Fool’s Errand. For one thing, the visual style of the Obra Dinn directly mimics computers fromThe Fool’s Errand’s era, with the default visual mode emulating the exact line computers The Fool’s Errand was built and played on. But also, the ways in which Obra Dinn presents its information and structures its puzzles is clearly in the lineage of older puzzle games like The Fool’s Errand. These games deeply entangle story and puzzle, presenting the player with a non-linearly revealed narrative (with new segments only revealed after finding some piece of information from the last), and expecting them to be hyper-observant, retrace their steps through previous narrative segments, and synthesize information from disparate, seemingly unconnected story beats. This type of veiled puzzle information is fairly common (though, admittedly, not super common) nowadays, but in the time of The Fool’s Errand, this kind of presentation was quite rare.

Perhaps more significant than these presentational elements, The Fool’s Errand is in fact the very first meta-puzzle video game – a puzzle game where a larger puzzle is made of a series of smaller puzzles. The puzzle game landscape in the late 80s was dominated by more ‘arcade-style’ puzzle games – puzzle games that were abstract, less narrative focused, and more about a high score than anything else. Tetris would be released for the first time outside of the USSR in the same year that The Fool’s Errand came out, and Minesweeper would come out just a few years later in 1990. These games, while certainly not trivial, did not ask the player to engage with them beyond what was visible on the screen at any given moment. The Fool’s Errand, on the other hand, almost requires a pen and paper to be completed, and frequently asks the player to cross-check information between story fragments, hop around from puzzle to puzzle and traverse various levels of puzzle and meta-puzzle depth all at once. In many ways, it was a very radical puzzle game, completely breaking the mold of what was possible with puzzle media at the time, and showing the depthful potential of puzzle games beyond just a high skill ceiling and high score.

While certainly not as impressive as Tetris’s 1.5 million sales in its 1990 NES release, The Fool’s Errand reached over 100,000 sales by 1989, which by desktop indie puzzle game standards at the time was a massive success. This game won a number of games publications’ Puzzle Game of the Year (again, in the same year that Tetris was first widely published) and has been named “Best Retro Game of All Time” or similar accolades in more recent times. Beyond just these achievements, however, it seems clear to me that this game was massively influential on the modern puzzle game landscape, and especially in the realm of meta-puzzle games and even meta-games. Some of the most popular and (for me) interesting puzzle games in recent years are clear descendents of The Fool’s Errand (I will be vague as to avoid spoilers as best I can). Baba is You’s multi-leveled map puzzles mirror The Fool’s Errand’s Sun’s Map, Tunic’s breaking of expectation with its interface elicits the same Eureka moment I experienced at 12, and even real world escape rooms’ stacked puzzles, where each puzzle’s solution provides new information for the next, falls squarely in line with The Fool’s Errand’s puzzle sequencing (these real world escape rooms, after all, originated from point-and-click escape the room video games, which in turn inherited their interaction mechanic from Myst, and likely their puzzle sensibilities from PC games like The Fool’s Errand). Cliff Johnson’s first game may not be widely remembered, but his innovation on the puzzle game genre resonates throughout modern puzzle games to this day.