In Unpacking, you play as a disembodied mouse cursor, an omnipresence that saturates every inch of the room. From your 2D isometric vantage point, you are tasked with unpacking moving boxes to place your items within the rooms of your new place of residence. While you can switch attention between rooms, you do not physically explore each room’s space due to your lack of bodily form.

While this description is a touch hyperbolic, it is not really inaccurate. Despite the absence of physical movement, how are you able to familiarize yourself with the space? When you open a box in the bathroom with a shirt that you know belongs in the bedroom, how are you able to immediately visualize which section of the closet you want to put this item in? When you’re finally finished and have emptied every box, why do you feel such an intimate connection to the spaces in each room?

In “Theorizing Navigable Space in Video Games”, Mark Wolf defines the structural elements in video games that shape how players understand and form expectations about the game’s space. According to Wolf, players create a “cognitive map” of how spaces in games are connected by the very act of navigating through those spaces (23). While most people associate navigation with physical movement, Wolf notes that navigation can sometimes manifest through the player’s gaze itself (23). This is what Unpacking does.

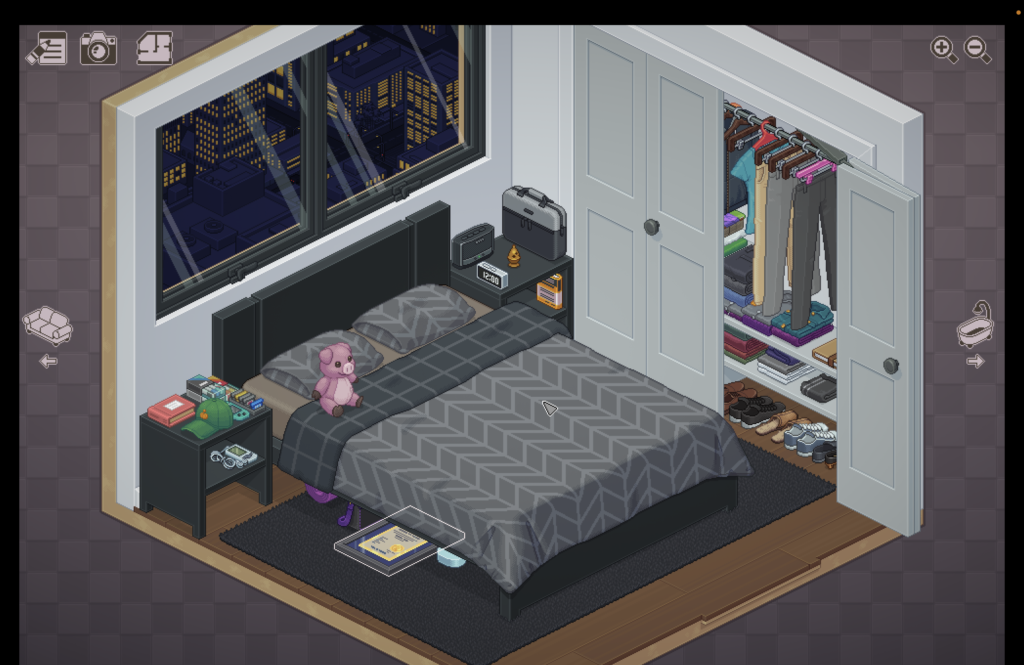

In unpacking their boxes, the player must navigate visually through each room’s space – each cabinet, drawer, and shelf – building a cognitive map which subsequently creates a familiarity and intimacy with the space. Similar to solving a complex maze, the player develops an understanding of how the various boundaries and obstacles in each room contribute to the availability of free space. Take the level where the main character moves into her boyfriend’s apartment.

In this level, space is scarce and free space is further limited by the boyfriend’s belongings. Similar to typical cases of space and movement in video games which “interfere or compete with navigational tasks”, the obstacles in the boyfriend’s apartment force the player to prioritize differently during their decision-making process (40). Rather than, say, focusing on arranging her items in an aesthetically pleasing way, the player must first prioritize fitting all of her items into the available space. Sometimes this involves overcoming the obstacles by shifting them around to create new free space. The space can even explicitly dictate the player’s decision-making, such as the lack of wall space denying the player from placing her diploma on the wall.

While the boyfriend’s apartment level creates an antagonistic relationship between the player and the game’s space, many of the other levels utilize the visual navigation mechanic to familiarize the player with the space and create a sense of home. While there are still items or 3rd-party belongings that represent obstacles impeding the player’s decision making, there is an excess of available space, allowing the player the creative freedom to navigate the space as they wish. The levels define spatial boundaries around the various areas in the room: desk space, closet space, shelf space. By navigating through these boundaries, the player is granted a “sense of progress and accomplishment as each space is conquered, completed, or added” (24). This sense of progress acclimates the player with the game space of each level, simulating how one develops a relationship with spaces of home that may have felt foreign or unfamiliar at first.

Wolf, Mark. (2011). Theorizing navigable space in video games.

“Movement through space” as Wolf theorizes it is represented very interestingly here—instead of physically seeing an avatar moving on screen, it is implied as items get placed down and moved around on screen. Navigation, as Wolf describes it, is also dependent on how the space is configured and manipulated over time. One thing I noticed while playing the game is that once I placed down an item, the game didn’t allow me to stack something on top of it, which is definitely something I do in real life. You mention other third party items existing in the spaces acting as boundaries or obstacles, and I wonder if the items themselves, once they are placed, could be considered boundaries. I think this is unique because instead of boundaries only being predetermined by the very code of the game, they are also determined by the player. This could also tie into Wolf’s discussion of conditional boundaries. You learn that you can’t stack items, but also you have a hand in creating the navigable space.